Category: Entertainment

Do we love the ‘Wicked’ movies because we hate innocence?

As I watched Jon M. Chu’s “Wicked: For Good” last week, I kept thinking about another, very different filmmaker: David Lynch.

Specifically, the Lynch that emerges from Alexandre Philippe’s excellent 2022 documentary “Lynch/Oz,” wherein we discover just how deeply the infamously surreal filmmaker was influenced by one of cinema’s sweetest fantasy films: the original “Wizard of Oz.”

In the era of #WitchTok … a story like ‘Wicked’ has built-in appeal.

Philippe’s film includes footage from a 2001 Q and A in which Lynch confirms the extent of his devotion: “There is not a day that goes by that I don’t think about ‘The Wizard of Oz.'”

The logic of fairyland

And that shouldn’t be surprising given how much it shows up in his work. From Glinda the Good Witch making an appearance in “Wild at Heart,” to the hazy, dreamlike depiction of suburbia in “Blue Velvet,” his films exist in a dual state between the realm of fairyland and the underworld.

Indeed, Lynch doesn’t reject either. In proper Buddhist fashion, these two forces exist in balance, equally potent and true. There is both good and evil in his world. Neither negates the other’s existence. And when darkness spills over into the light, it may be tragic, but it is also just another part of the world. Like Dorothy, his protagonists find themselves walking deeper into unknown territory. The protagonists of his films truly “aren’t in Kansas anymore.”

“The Wizard of Oz” is potent because it captures the logic of fairyland better than almost any film ever made. Channeling the fairy stories of J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis Carroll, and George MacDonald, it transports the mind to a realm that is more real than real, where even the most dire intrusion of evil can be set right according to simple moral rules.

As G.K. Chesterton famously puts it:

Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

Wicked good

“Wicked” and its new sequel reject this comforting clarity for something altogether more “adult” and ambiguous. Instead of presenting good and evil as objective realities that can be discerned and defeated, the films show how political authorities manipulate those labels to scapegoat some and exalt others.

They do so by swapping the original’s heroes and villains. The Wonderful Wizard is a cruel tyrant. Glinda is foppish and self-obsessed. Dorothy is the unwitting tool of a corrupt regime. And Elphaba — the so-called Wicked Witch — is reimagined as a sympathetic underdog with a tragic backstory, a manufactured villain invented to keep Oz unified in ire and hatred.

Elphaba exudes a whiff of Milton’s Lucifer — an eternal rebel in a tragic quest to upend the moral order. But unlike “Paradise Lost,” “Wicked” presents rebellion against its all-powerful father figure not as a tragic self-deception, but as a justified response to systemic cruelty.

Witch way?

“Wicked: For Good” takes the ideas of its predecessor even further than mere rebellion. If “Wicked: Part One” is about awakening to the world’s realities and becoming radicalized by them, “Wicked: For Good” is about the cost of selling out — the temptation to compromise with a corrupt system and the soul-crushing despair that follows.

This is where the irony of the film’s title, “Wicked: For Good” comes in. Once a person sees the world for what it truly is, they can’t go back without compromising themselves. They’ve “changed for good.” They’ve awakened and can’t return to sleep.

It’s worth considering why the “Wicked” franchise is so wildly popular. Gregory Maguire’s original 1995 novel has sold 5 million copies. The 2003 stage show it inspired won three Tony Awards and recently became the fourth longest-running Broadway musical ever. And the first film grossed $759 million last winter, with the sequel poised to make even more money.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that this outsize success comes at a time when Wicca and paganism have grown into mainstream cultural forces. In the era of #WitchTok, in which self-proclaimed witches hex politicians and garner billions of views on social media, a story like “Wicked” has built-in appeal. It offers glamorous spell-casting and a romantic tale of resistance to authority.

RELATED: ‘Etsy witches’ reportedly placed curses on Charlie Kirk days before assassination

Photo by The Salt Lake Tribune / Contributor via Getty Images

Photo by The Salt Lake Tribune / Contributor via Getty Images

A bittersweet moral

The temptation of witchcraft is one that always hovers over our enlightened and rationalistic society. Particularly for young women, witchcraft offers a specific form of autonomy and power — over body, spirit, and fate — that patriarchal societies often deny. Many view witchcraft as progressive and empowering; “witchy vibes” have become a badge of identity.

Thus the unsettling imagery of Robert Eggers’ 2015 film “The Witch” comes into focus: A satanic coven kidnaps and kills a Puritan baby, seduces a teenage girl, and gains the power to unsubtly “defy gravity” through a deal with the devil.

“Wicked” is all about this power to transcend. Even as its protagonist grows despairing in the second film and abandons her political quest for the freedom of the wastelands, the film presupposes that it is better to resist or escape a corrupt system than submit to it.

Ultimately, the two films leave their audience with a bittersweet moral: Society is dependent on scapegoats. The Platonic noble lie upon which all societies rest cannot be escaped — but it can be redirected. A new civic myth can be founded that avoids sacrificing the vulnerable and overthrows the demagogues atop Mount Olympus. And the witches play the central role in overturning the world of Oz. Their rebellion sets it free.

But because the films blur the clear, objective distinction between good and evil — even while acknowledging that real evil exists — the characters in “Wicked” often drift in moral grayness, defining themselves mainly in relation to power. The world becomes overbearing, radicalizing, and morally unstable.

Sad truth

This is far afield from the vision of Oz presented in the 1939 film, the one David Lynch venerated as vital to his understanding of the world. But it reflects how modern storytellers often grapple with Oz. Almost every sequel or spin-off struggles to recapture the sincerity of the original. The 1985 sequel “Return to Oz” reimagined the land with a dark-fantasy twist. 2013’s “Oz the Great and Powerful” comes closest to the original tone but centers on fraudulence and trickery.

“Wicked,” too, falls in line with the modern tendency to subvert and complicate traditional stories of good versus evil. “Frozen,” “The Shape of Water,” “Game of Thrones,” and “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” all explore morally conflicted worlds where bravery is futile or where Miltonian rebellion is celebrated.

Of course, seeing the stories of our childhood with a jaundiced adult eye can be quite entertaining; it’s perfectly understandable why even those not in covens love these films. They are well-made, well-performed, and especially irresistible to former theater kids (I am one).

Their popularity isn’t inherently bad either. They are perfectly fine in isolation. It is only when we contrast them with the clarity and beauty of the original — and place them within the context of our society — that a sad truth emerges: Finding fairyland is hard. Most of us prefer to live in the Lynchian underworld.

SHORT N’ SWEET: White House Drops Curt Response After Carpenter Complains About ICE Using Song

The White House came out swinging Tuesday after pop star Sabrina Carpenter accused the administration of hijacking her music for an ICE video, calling the move “evil and disgusting.

I thought I was too old to fall in love again — until two chords proved me wrong

I have a new favorite band. I know that sounds weird. I’m not a teenager. I’m a grown adult man.

I was in my car when I first heard the song “Jupiter” on the alternative music station. It began with a distinctive guitar part, two chords played in a simple rhythmic pattern.

An actual band is too much like a gang. Or a terrorist group. Four white guys roaming around the country in a van? We better have the FBI look into that.

It was super catchy. Very simple. Nice groove. It didn’t sound like anything else on the radio. The band is called Almost Monday.

Smoothed and removed

I downloaded “Jupiter” and put it on a playlist. It stood out, even among some classic songs. I found myself humming it during my day. And then needing to listen to it when I got home.

A month or two later, another new song by Almost Monday came out, “Can’t Slow Down.” It had a similar repetitive guitar riff. But in this song, there was a great bass part as well.

Both songs had a slick quality. Super produced. Really clean and effortless.

I think of music like that as “not letting you in.” You, the listener, are experiencing music so smooth and polished, you can’t imagine actual people playing it.

You can’t picture the band members. They’re projecting a wall of glossy perfection. And you can’t see through it.

*******

I downloaded “Can’t Slow Down” and put that on a playlist. But it sounded best on my car radio while I was driving. Fortunately, it was on heavy rotation, and I drive a lot. So I heard it constantly.

“Jupiter” was still playing continuously as well. The two songs were like a one-two punch. By July, it seemed Almost Monday was the breakout band of the summer.

“Jupiter” and “Can’t Slow Down” were definitely my “summer songs.” And probably a lot of other people’s as well.

It was almost like Almost Monday had become my new favorite band.

Trends to the end

I haven’t had a favorite band in a long time. I didn’t even think I was capable of having a favorite band again, to be honest. I mean, I still listen to the radio. I still follow the trends in music.

I enjoyed the “yacht rock” trend from a couple of years ago. But that was more of a joke. But even joke-trends can produce good music.

If I were a music critic, I would describe Almost Monday as “post-yacht rock, California pop.” Smooth, catchy melodies. Clever lyrics. No politics, no depressing thoughts. A strong Southern California vibe (the band is from San Diego).

*******

Looking back, my first favorite bands were Led Zeppelin and Aerosmith. That was in high school. In college, it was Echo and the Bunnymen. When I lived in San Francisco after college, it was the Smiths.

All these bands became like close friends to me. I would miss them if I didn’t hear them at least once a day. I needed my fix.

When I got into my 30s, I became more of a general fan. That was when grunge happened. I liked all those bands, but none really stood out as my favorite.

After grunge, there were many music groups I liked. Radiohead. Interpol. Elliott Smith. Sufjan Stevens’ “Carrie & Lowell” album. But I wouldn’t say any of these were “my favorite band.”

The trouble with happiness

One thing I should say: I don’t usually enjoy music like Almost Monday. I was never into that carefree, happy-sunshine, California vibe. I typically like heavier, moodier stuff.

But maybe because the tone of society is so dark and fraught right now, the lightness of their music feels almost revolutionary. How dare they be so easy-going. So outwardly cheerful. Who do they think they are?

Also, they’re a bunch of white guys. Which is not exactly in fashion. Shouldn’t they have some women and some racial diversity in their group?

And even being “a band” seems retrograde and reactionary. Current pop music is about individual stars. Chappell Roan. Benson Boone. Sabrina Carpenter. Bad Bunny.

These are individual “artists” with specific marketing concepts and replaceable musicians.

An actual band is too much like a gang. Or a terrorist group. Four white guys roaming around the country in a van? We better have the FBI look into that.

*******

All summer I listened to “Can’t Slow Down” and “Jupiter,” multiple times a day. But I’d still never actually seen the group. I didn’t feel a need to.

But then one night, I had the TV on, and I heard Jimmy Kimmel introduce the group on his show. I hurried over to the TV and turned up the sound.

They played “Can’t Slow Down.” They were super simple in their stage presentation. Just four guys. Singer, bass, drums, guitar.

They had no amps, I noticed. There was almost nothing on the stage. The guitarist played that one simple repeating progression.

They were super chill. The singer moved around a little. The guitarist and bassist just played. The drummer drummed. They didn’t let you in.

Really, it was fantastic. But would America appreciate their understated cool? Their simplicity? Their Zen-like reserve?

They’d had two smash-hit singles on alternative radio that summer. But what did that mean in the music biz? Was “alternative music” still a big market? Do young people even listen to music anymore? How do bands make money nowadays?

RELATED: Where have all the rock bands gone?

Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images

Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images

I’ll see you in September

In September, I rode a ferry up to Alaska. This was not a cruise. It was a ferry, with dogs and trucks and locals. It took three days. There was no TV on board, nothing much to do.

That’s when I realized how close I felt to Almost Monday. I would hang around on deck for a couple of hours, then go back to my bunk and listen to “Jupiter” and “Can’t Slow Down.”

I dug up some of their other songs that I’d downloaded. Now I had time to listen to these closely and develop new favorites.

It was fun because in my mind these were “summer songs,” but every hour we steamed north on the ferry, it got colder.

Summer was not fading away over a month or two, like usual. It was fading hour by hour.

So I binged on the summer sounds of Almost Monday, as the skies grew dark and people on deck started wearing down parkas.

*******

A favorite band is like a best friend. It is the first person you want to talk to in the morning. And the last person you want to hear from before you go to bed. During the day, you don’t need to be in constant contact, but you’re relieved when you’re in their presence again.

*******

Now I’m back in Portland. It’s wet and cold, but I still listen to Almost Monday every day.

I hope they make it big. Or big enough to never have to get normal jobs.

That’s all I ever wish for, for my fellow creatives: I hope they make some money. I never wish for them wild success or huge fame. That can be bad for a person.

But I do want them to make enough money that they can be artists for the rest of their lives. And not have to worry about paying their rent.

In music, sometimes all it takes is to write a couple great songs (and own the publishing rights). I know Almost Monday has already accomplished that. So hopefully the rest is gravy.

The Spectator P.M. Ep. 171: Meghan Markle Demands to Be Called by Her Title Everywhere

Anyone expecting Meghan Markle’s presence is formally greeted by someone announcing her as “Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.” A recent interview…

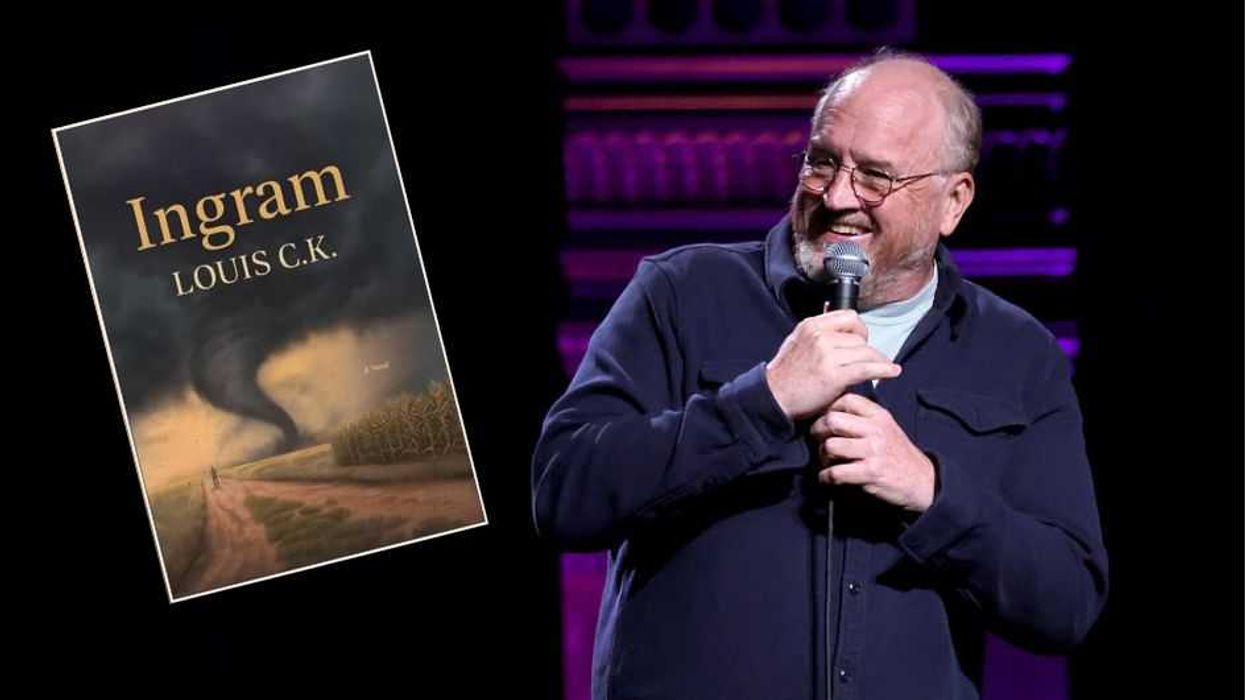

Louis CK’s ‘Ingram’: Skilled comic spews self-indulgent self-abuse

For more than two centuries, the great American novel has tempted writers who dreamed of capturing the country’s soul between two covers.

From Melville’s “Moby-Dick” to Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” from Faulkner’s haunted South to Steinbeck’s dust-caked plains, these novels shaped the way Americans saw themselves. Even in decline, the form still attracted giants. Updike, Roth, Morrison — writers who made words shine and sentences sing. Each tried to show what it means to be American: to dream, to stumble, and to start again.

To compound matters, ‘Ingram’ isn’t just a story of exploration, but also one of self-exploration, in the most literal and least appealing sense.

Now comes comedian, filmmaker, and repentant sex pest Louis C.K. to try his hand at what turns out to be … a not-great American novel. In truth, it’s awful.

Road to nowhere

“Ingram” reads like a road map to nowhere — meandering, bloated, and grammatically reckless. The prose wanders as if written under anesthesia. Sentences stretch, then sag. The paragraphs arrive in puddles, not lines. There’s an energy in C.K.’s comedy — a kind of desperate honesty — that, on stage, electrifies. But on the page, that same honesty slips into self-indulgence. The book is less “On the Road” and more off the rails.

To be clear, I love his comedy. I’ve seen him live and will see him again in the new year. He remains one of the most gifted observers of human absurdity alive — a man who can mine a half-eaten slice of pizza for existential truth. But this is not about comedy. This is about writing. And C.K. cannot write. The pacing, the architecture, the restraint — none of it is there.

Rough draft

The story unfolds in a version of rural Texas that seems to exist only in C.K.’s imagination, a land of dull prospects and even duller minds. At its center is Ingram, a poor, half-feral boy raised in poverty and pushed out into the world by a mother who tells him she has nothing left to offer. His education consists of hardship and hearsay. He treats running water like sorcery and basic plumbing like black magic. C.K. calls it “a young drifter’s coming of age in an indifferent world,” but it reads more like rough stand-up notes bound by mistake.

The writing is atrocious. Vast portions of the book read like this:

I couldn’t see my eyes, but I knew what was on my throat was a hand by the way it was warm and tightening and quivering like you could feel the thinking inside each finger, which were so long and thick that one of them pressed hard against the whole side of my face.

Or this:

I sat up, rubbing my aching neck til my breath came back regular, and I crawled out the tent flap myself, finding the world around me lit by the sun, which, just rising, was still low enough in the sky to throw its light down there under the great road, which was once again roaring and shaking above me.

Sentences stretch on like prison terms, suffocated by their own syntax, gasping for punctuation. The dialogue is somehow worse. Ingram’s conversations with the drifters and degenerates he meets on his journey stumble from cliché to confusion, the rhythm of speech giving way to nonsensical babble.

RELATED: Bill Maher and Bill Burr agree Louis CK should be welcomed back in Hollywood

Photo by Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

Photo by Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

A gripping tale

To compound matters, “Ingram,” isn’t just a story of exploration, but also one of self-exploration, in the most literal and least appealing sense. There’s a staggering amount of masturbation. C.K. doesn’t so much write about shame as relive it, page after sticky page. His public fall from grace plays out again and again, only now under the pretense of art. It’s less confession than repetition — self-absolution by way of self-abuse, and somehow still not funny.

Any comparisons to writers like Bukowski or Barry Hannah are little more than wishful thinking. Bukowski was grimy, but in a graceful way. He wrote filth with style, turning hangovers into hymns.

Hannah’s madness had a tune to it, strange but unmistakably his own. Even Hunter S. Thompson, at his most incoherent, had velocity. His sentences tore through the page, drug-fueled but deliberate.

C.K.’s writing has none of that. He tries to channel Americana — the heat, the highways, the hard men who dream of escape — but his clumsy prose ensures the only thing channeled is confusion. As C.K. recently told Bill Maher, he did no research for the book, and that much is evident from the first page. His characters talk like they were written by a man who’s only seen Texas through “No Country for Old Men.”

Don’t quit your day job

In the history of American letters, many great writers have fallen. Hemingway drank himself into oblivion; Mailer stabbed his wife; Capote drowned in his own decadence. But their sentences still stood. Their craft was the redemption. With “Ingram,” C.K. has no such refuge. The book exposes the limits of confession as art — that point where self-exposure turns into self-immolation. It could have been great; instead, it’s the very opposite. The only thing it proves is that writing and performing are different callings. Comedy forgives indiscipline. Literature doesn’t.

The great American novel has survived worse assaults — from bored professors, from self-serious minimalists, from MFA factories that mistake verbosity for vision. But rarely has it been dragged so low by someone so convinced of his brilliance. There’s perverse poetry in it, though. A man who was caught with his pants down now delivers a novel that never pulls them back up.

Stephen Colbert Gushes over Mamdani: ‘Everyone in America Sees Something in’ His Democratic Socialist Message

Stephen Colbert gushed over New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, falsely declaring that “everyone in America sees something in” the 34-year-old’s Democratic Socialist message.

The post Stephen Colbert Gushes over Mamdani: ‘Everyone in America Sees Something in’ His Democratic Socialist Message appeared first on Breitbart.

Sore Liu-ser: Multimillionaire ‘Kill Bill’ star gripes about ‘Caucasian’-heavy Hollywood

Boo-hoo, Lucy Liu.

The veteran actress is in the awards season mix for “Rosemead,” the tale of an immigrant grappling with a troubled teenage son. That means she’s working the press circuit, talking to as many media outlets as she can to promote a possible Best Actress nomination.

No more peeks at Erivo’s extended, Freddy Krueger-like nails or Grande waving away a helicopter overhead as if it were about to swoop down on them.

If you think political campaigns are cynical, you haven’t seen an actor push for a golden statuette. That may explain why Liu shared her victimhood story with the Hollywood Reporter.

Turns out the chronically employed star (123 acting credits, according to IMDB.com) hasn’t been employed enough, by her standards.

I remember being like, “Why isn’t there more happening?” … I didn’t want to participate in anything where I felt like they weren’t even taking me seriously. How am I being given these offers that are less than when I started in this business? It was a sign of disrespect to me, and I didn’t really want that. I didn’t want to acquiesce to that … I cannot turn myself into somebody who looks Caucasian, but if I could, I would’ve had so many more opportunities.

Liu has had the kind of career most actors would kill to duplicate. That doesn’t play on the identity politics guilt of her peers though. Nor is it fodder for a “woe is me” awards speech …

Rest for the ‘Wicked’

That’s a wrap!

The “Wicked: For Good” press push got the heave-ho earlier this week when star Cynthia Erivo reportedly lost her voice. Co-star Ariana Grande pulled out of her appearances in solidarity.

Yup. Not remotely suspicious.

The duo made way too many headlines last year during their initial “Wicked” press tour. Why? It was just … weird. Odd. Creepy. The stars’ emaciated appearance didn’t help, but their kooky, collective affect was off-putting, to be kind.

Even the Free Press called out the duo’s sadly emaciated state.

They trotted out more of the same for round two, and someone had the good sense to yank them off the stage before the bulletproof sequel hit theaters Nov. 21.

No more peeks at Erivo’s extended, Freddy Krueger-like nails or Grande waving away a helicopter overhead as if it were about to swoop down on them.

Any publicity is good publicity, right? Not when it’s wickedly cringe …

RELATED: ‘Last Days’ brings empathy to doomed Sentinel Island missionary’s story

Vertical

Vertical

Face for radio

John Oliver thinks it’s 1985.

HBO’s far-left lip flapper is furious that the Trump administration stripped NPR of its federal funding. Who will ignore senile presidents and laptop scandals without our hard-earned dollars?

Think of the children!

Never mind that Americans have endless ways to access news, from AM radio to TV, satellite, cable, and streaming options. Heck, just pick up a $20 set of rabbit ears, and you’ll get a crush of local TV stations in many swathes of the country.

You have to live in a bunker a hundred feet below the earth to avoid the news.

Oliver, to his credit, put his money where his mouth is. Or at least, your money. He set up a public auction to raise cash for NPR stations.

Why? Because we’re all going to croak without it. That’s assuming you didn’t die following the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the lack of net neutrality.

“Public radio saves lives. The emergency broadcast system. Without it, people would die.”

A second-rate satirist might have a field day with anyone pushing the “you’ll die without X, Y, or Z” card. Alas Oliver doesn’t warrant that ranking …

‘Running’ on empty

Rising star status ain’t what it used to be.

Glen Powell seemed like the next Tom Cruise for a hot minute. Handsome. Affable. Unwilling to insult half the country. He stole a few moments during “Top Gun: Maverick” and powered a mediocre rom-com — 2023’s “Anyone but You” — into a $220 million global hit.

So when Hollywood handed him the keys to the “Running Man” remake, the industry assumed he had finally arrived. Give him his “I’m on the A-List” smoking jacket.

That’s until the remake’s opening weekend numbers came in. Or rather trickled in. That $16 million-plus haul just won’t cut it.

Now Powell’s next film is under the microscope. The project dubbed “Huntington” just got a last-minute name change to “How to Make a Killing.” The film follows Powell’s character as he tries to ensure he’ll inherit millions from his uber-wealthy family. That’s despite getting cast out of the clan’s good graces.

The movie now has a Feb. 20 release date, hardly a key window for an A-lister like Powell.

Then again, his time on the A-list may have already expired.

‘A House of Dynamite’: Netflix turns nuclear war into an HR meeting

Netflix’s thriller “A House of Dynamite” very much wants to teach us something about the folly of waging war with civilization-ending weapons. The lesson it ends up imparting, however, has more to do with the state of contemporary storytelling.

The film revolves around a high-stakes crisis: an unexpected nuclear missile launched from an unspecified enemy and aimed directly at Big City USA. We get to see America’s defense apparatus deal with impending apocalypse in real time.

It seems the best Ms. Bigelow, Mr. Oppenheim, and the team at Netflix can offer up is a lukewarm ‘nukes are bad, mmkay?’

Triple threat

“Revolves” is the operative word here. The movie tells the same story three times from three different vantage points — each in its own 40-minute segment. From first detection to the final seconds before detonation, we watch a bevy of government elites on one interminable red-alert FaceTime, working out how to respond to the strike.

This is the aptly named screenwriter Noah Oppenheim’s second disaster outing for the streamer; he recently co-created miniseries “Zero Day,” which features Robert De Niro investigating a nationwide cyberattack.

That series unspooled a complicated and convoluted conspiracy in the vein of “24.” “A House of Dynamite” clearly aims for something more grounded, which would seem to make accomplished Kathryn Bigelow perfect for the job.

And for the film’s first half-hour she delivers, embedding the viewer with the military officers, government officials, and regular working stiffs for whom being the last line of America’s defense is just another day at the office … until suddenly it isn’t. The dawning horror of their situation is as gripping as anything in “The Hurt Locker” or “Zero Dark Thirty.”

Then it happens two more times.

On repeat

In Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night,” Duke Orsino laments a repetitive song growing stale: “Naught enters there of what validity and pitch soe’er, but falls into abatement and low price.”

Or put another way, the tune, not realizing its simple beauty, sings itself straight into worthlessness.

And somehow, this manages to be only part of what makes “A House of Dynamite” so unappealing. Our main characters — including head of the White House Situation Room (Rebecca Ferguson), general in charge of the United States Northern Command (Tracy Letts), and the secretary of defense (Jared Harris) — offer no semblance of perspicacity, stopping frequently to take others’ feelings into account before making decisions, all while an ICBM races toward Chicago. From liftoff to impact in 16 minutes or less, or your order free.

Missile defensive

So thorough is this picture of incompetence that the Pentagon felt compelled to issue an internal memo preparing Missile Defense Agency staff to “address false assumptions” about defense capability.

One can hardly blame officials when, in the twilight of the film, we’re shown yet another big-screen Obama facsimile (played by British actor Idris Elba) putting his cadre of sweating advisers on hold to ring Michelle, looking for advice on whether his course of action should be to nuke the whole planet or do nothing. The connection drops — she is in Africa, after all, and her safari-chic philanthropy outfit doesn’t make the satellite signal any stronger. He puts the phone down and continues to look over his black book of options ranging “from rare to well done,” as his nuclear briefcase handler puts it.

And then the movie ends. The repetitive storylines have no resolution, and their participants face no consequences. The single ground missile the U.S. arsenal managed to muster up — between montages of sergeants falling to their knees at the thought of having to do their job — has missed its target.

Designated survivors — with the exception of one high-ranking official who finds suicide preferable — rush to their bunkers. The screen fades to black, over a melancholy overture. Is it any wonder that audiences felt cheated? After sitting through nearly two hours of dithering bureaucrats wasting time, their own time had been wasted by a director who clearly thinks endings are passé.

No ending for you

If you find yourself among the unsatisfied, Bigelow has some words for you. In an interview with Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, she justified her film’s lack of a payoff thusly:

I felt like the fact that the bomb didn’t go off was an opportunity to start a conversation. With an explosion at the end, it would have been kind of all wrapped up neat, and you could point your finger [and say] “it’s bad that happened.” But it would sort of absolve us, the human race, of responsibility. And in fact, no, we are responsible for having created these weapons and — in a perfect world — getting rid of them.

Holy Kamala word salad.

RELATED: Phones and drones expose the cracks in America’s defenses

Photo by dikushin via Getty Images

Photo by dikushin via Getty Images

Bigelow-er

For much of her career, director Kathryn Bigelow has told real stories in interesting ways that — while not always being the full truth and nothing but the truth — were entertaining, well shot, and depicted Americans fulfilling their manifest destiny of being awesome.

That changed with Bigelow’s last film, 2017’s “Detroit,” a progressive, self-flagellating depiction of the 1967 Detroit race riots (final tally: 43 deaths, 1,189 injured) through the eyes of some mostly peaceful black teens and the devil-spawn deputy cop who torments them. “A House of Dynamite” continues this project of national critique.

But what, exactly, is the point? It seems the best Ms. Bigelow, Mr. Oppenheim, and the team at Netflix can offer up is a lukewarm “nukes are bad, mmkay?” This is a lecture on warfare with the subtlety of a John Lennon song, set in a world where the fragile men in charge must seek out the strong embrace of their nearest girlboss.

It’s no secret that 2025 carries a distinct “end times” energy — a year thick with existential threats. AI run amok, political fracture edging toward civil conflict, nuclear brinkmanship, even the occasional UFO headline — pick your poison. And it’s equally obvious that the internet, not the cinema, has become the primary arena where Americans now go to see those anxieties mirrored back at them.

“A House of Dynamite” is unlikely to reverse this trend. If this is the best Hollywood’s elite can come up with after gazing into the void, it’s time to move the movie industry to DEFCON 1.

The Spectacle Ep. 300: Why Movies Suck: Screenwriter Lou Aguilar Tells the Story

As the struggling film industry faces an all-time low in ratings and box office performance, can conservatives step up to…

‘Nuremberg’: Russell Crowe’s haunting portrayal of Nazi evil

Say what you will about Russell Crowe, but he has never been a run-of-the-mill actor.

At his best, he surrenders to the role. This is an artist capable of channeling the full range of human contradictions. From the haunted integrity of “The Insider” to the brute nobility of “Gladiator,” Crowe once seemed to contain both sinner and saint, pugilist and philosopher.

In a time when truly commanding leading men are all but extinct, Crowe remains — carrying the weight, the wit, and the weathered grace of a bygone breed.

Then, sometime after “A Beautiful Mind,” the light dimmed. The roles got smaller, the scandals bigger.

There were still flashes of brilliance — “American Gangster” with Denzel Washington, “The Nice Guys” with Ryan Gosling — proof that Crowe could still command attention when the script was worth it. But for every film that landed, two missed the mark: clumsy thrillers, lazy comedies, and a string of forgettable parts that left him without anchor or aim. His career drifted between prestige and paycheck, part self-sabotage, part Hollywood forgetting its own.

Exploring the abyss

But now the grizzled sexagenarian returns with “Nuremberg” — not as a comeback cliché, but as a reminder that the finest actors are explorers of the human abyss. And Crowe, to his credit, has never been afraid to go deep.

In James Vanderbilt’s new film, the combative Kiwi plays Hermann Goering, the Nazi Reichsmarschall standing trial for his part in history’s darkest chapter. The movie centers on Goering’s psychological chess match with U.S. Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who becomes both fascinated and repulsed by the man before him. Goering, with his vanity, intelligence, and theatrical self-pity, is a criminal rehearsing for immortality.

The film unfolds as a dark study of guilt and self-deception. Kelley, played with that familiar, hollow-eyed tension of Rami Malek, sets out to dissect the anatomy of evil through Goering’s mind. Yet the deeper he digs, the more he feels the ground give way beneath him — the line between witness and accomplice blurring with every exchange.

Disturbingly human

Crowe’s Goering is not the slobbering villain of old war films. He’s disturbingly human, even likeable. He jokes, he reasons, he charms. He’s a man who knows how to disarm his enemy by appearing civil — and therein lies the horror. It’s a performance steeped in Hannah Arendt’s famous concept of the “banality of evil”: the idea that great atrocities are rarely committed by psychopathic monsters but by ordinary people made monstrous — individuals who justify cruelty through bureaucracy, obedience, or ideology.

Arendt wrote those words after watching Adolf Eichmann, another Nazi functionary, defend his role in the Holocaust. She was struck not by his madness but his mildness — his desire to be seen as merely following orders. Crowe’s Goering embodies that same terrifying normalcy. He doesn’t see himself as a villain at all, but as a patriot — wronged, misunderstood, and unfairly judged. It’s his charm, not his cruelty, that unsettles.

The brilliance of Crowe’s performance is that he resists caricature. He reminds us that evil doesn’t always wear jackboots. Sometimes it smiles, smokes, and quotes Shakespeare. It’s the kind of role only a mature actor can pull off — one who has met his own demons and understands that evil seldom announces itself.

It is also, perhaps, the perfect role for a man who has spent decades wrestling with his own legend. Crowe was once Hollywood’s golden boy — rugged, brooding, every inch the leading man — but the climb was steep and the fall steeper. Fame, like empire, demands endless victories, and Crowe, ever restless, grew weary of the war.

RELATED: Father-Son Movie Bucket List

Getty Images

Getty Images

A bygone breed

With “Nuremberg,” he hasn’t returned to chase stardom but to confront something larger — the unease that hides beneath every civilized surface. Goering, after all, was no brute. He was cultured, eloquent, even magnetic — proof that wisdom offers no wall against wickedness. And in a time when truly commanding leading men are all but extinct, Crowe remains — carrying the weight, the wit, and the weathered grace of a bygone breed.

At one point in the film, Goering throws America’s own hypocrisies back at Kelley: the atomic bomb, the internment of Japanese-Americans, the collective punishment of nations. It’s a rhetorical trick, but it lands. Crowe delivers those lines with the oily confidence of a man who knows that moral purity is a myth and that self-righteousness is often evil’s most convenient disguise.

The film may not be perfect. Its pacing lags at times, and its historical framing flirts with melodrama. But Crowe’s performance cuts through the pretense like a scalpel. There’s even a dark humor in how he toys with his captors — the court jester of genocide, smirking as the world tries to comprehend him.

Crowe’s Goering is, in the end, a mirror. Not just for the psychiatrist across the table, but for us all. The machinery of horror is rarely built by fanatics, but by functionaries convinced they’re simply doing their jobs.

Crowe’s performance reminds us why acting, when done with conviction, can still rattle the soul. His Goering is maddening and mesmeric. He captures the human talent for self-delusion, the ease with which conscience can be out-argued by ambition or fear. “Nuremberg” refuses to let the audience look away. It reminds us that every civilization carries the seed of its own undoing and every human heart holds a shadow it would rather not confront.

Russell Crowe is back, tipped for another Oscar — and in an age when Hollywood produces so few films worthy of our time or our money, I, for one, hope he gets it.

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Former New Jersey Governor Who Took Over For Scandal-Plagued Predecessor Dies January 11, 2026

- Philadelphia Sheriff Goes Viral For Threatening ICE January 11, 2026

- The Obamacare subsidy fight exposes who Washington really serves January 11, 2026

- The crisis of ‘trembling pastors’: Why church leaders are ignoring core theology because it’s ‘political’ January 11, 2026

- Dobol B TV Livestream: January 12, 2026 January 11, 2026

- Ogie Diaz ukol kay Liza Soberano: ‘Wala siyang sama ng loob sa akin. Ako rin naman…’ January 11, 2026

- LOOK: Another ‘uson” descends Mayon Volcano January 11, 2026