Category: Tech

Elon Musk’s Vision of the Future: Work Is ‘Optional,’ Money Is Irrelevant as AI and Robots Take Over Everything

Elon Musk shared his vision of the future at the U.S.-Saudi Investment Forum in Washington, DC this week. According to the tech tycoon, work will be optional and money will lose all meaning as AI-powered robots take over every aspect of the economy over the next two decades.

The post Elon Musk’s Vision of the Future: Work Is ‘Optional,’ Money Is Irrelevant as AI and Robots Take Over Everything appeared first on Breitbart.

GOD-TIER AI? Why there’s no easy exit from the human condition

Many working in technology are entranced by a story of a god-tier shift that is soon to come. The story is the “fast takeoff” for AI, often involving an “intelligence explosion.” There will be a singular moment, a cliff-edge, when a machine mind, having achieved critical capacities for technical design, begins to implement an improved version of itself. In a short time, perhaps mere hours, it will soar past human control, becoming a nearly omnipotent force, a deus ex machina for which we are, at best, irrelevant scenery.

This is a clean narrative. It is dramatic. It has the terrifying, satisfying shape of an apocalypse.

It is also a pseudo-messianic myth resting on a mistaken understanding of what intelligence is, what technology is, and what the world is.

The world adapts. The apocalypse is deferred. The technology is integrated.

The fantasy of a runaway supermind achieving escape velocity collides with the stubborn, physical, and institutional realities of our lives. This narrative mistakes a scalar for a capacity, ignoring the fact that intelligence is not a context-free number but a situated process, deeply entangled with physical constraints.

The fixation on an instantaneous leap reveals a particular historical amnesia. We are told this new tool will be a singular event. The historical record suggests otherwise.

Major innovations, the ones that truly resculpted civilization, were never events. They were slow, messy, multi-decade diffusions. The printing press did not achieve the propagation of knowledge overnight; its revolutionary power was in the gradual enabling of the secure communication of information, which in turn allowed knowledge to compound. The steam engine unfolded over generations, its deepest impact trailing its invention by decades.

With each novel technology, we have seen a similar cycle of panic: a flare of moral alarm, a set of dire predictions, and then, inevitably, the slow, grinding work of normalization. The world adapts. The apocalypse is deferred. The technology is integrated. There is little reason to believe this time is different, however much the myth insists upon it.

The fantasy of a fast takeoff is conspicuously neat. It is a narrative free of friction, of thermodynamics, of the intractable mess of material existence. Reality, in contrast, has all of these things. A disembodied mind cannot simply will its own improved implementation into being.

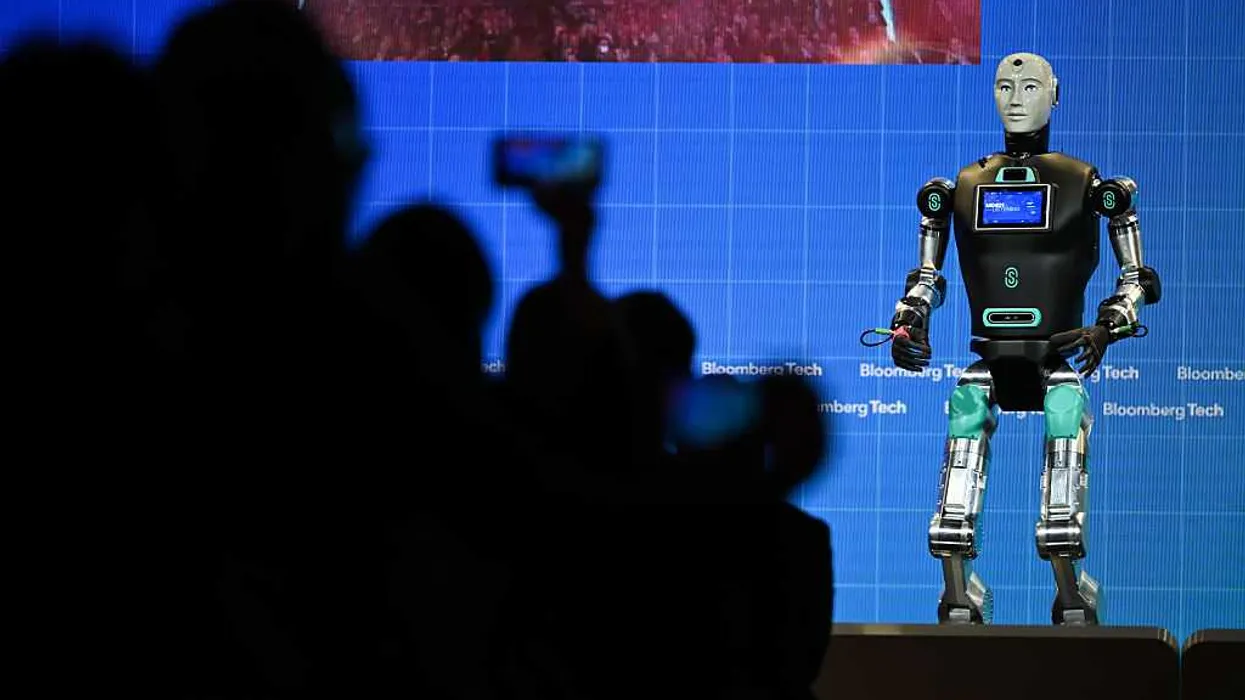

Photo by Arda Kucukkaya/Anadolu via Getty Images

Photo by Arda Kucukkaya/Anadolu via Getty Images

Any improvement, recursive or otherwise, encounters physical limits. Computation is bounded by the speed of light. The required energy is already staggering. Improvements will require hardware that depends on factories, rare minerals, and global supply chains. These things cannot be summoned by code alone. Even when an AI can design a better chip, that design will need to be fabricated. The feedback loop between software insight and physical hardware is constrained by the banal, time-consuming realities of engineering, manufacturing, and logistics.

The intellectual constraints are just as rigid. The notion of an “intelligence explosion” assumes that all problems yield to better reasoning. This is an error. Many hard problems are computationally intractable and provably so. They cannot be solved by superior reasoning; they can only be approximated in ways subject to the limits of energy and time.

Ironically, we already have a system of recursive self-improvement. It is called civilization, employing the cooperative intelligence of humans. Its gains over the centuries have been steady and strikingly gradual, not explosive. Each new advance requires more, not less, effort. When the “low-hanging fruit” is harvested, diminishing returns set in. There is no evidence that AI, however capable, is exempt from this constraint.

Central to the concept of fast takeoff is the erroneous belief that intelligence is a singular, unified thing. Recent AI progress provides contrary evidence. We have not built a singular intelligence; we have built specific, potent tools. AlphaGo achieved superhuman performance in Go, a spectacular leap within its domain, yet its facility did not generalize to medical research. Large language models display great linguistic ability, but they also “hallucinate,” and pushing from one generation to the next requires not a sudden spark of insight, but an enormous effort of data and training.

The likely future is not a monolithic supermind but an AI service providing a network of specialized systems for language, vision, physics, and design. AI will remain a set of tools, managed and combined by human operators.

To frame AI development as a potential catastrophe that suddenly arrives swaps a complex, multi-decade social challenge for a simple, cinematic horror story. It allows us to indulge in the fantasy of an impending technological judgment, rather than engage with the difficult path of development. The real work will be gradual, involving the adaptation of institutions, the shifting of economies, and the management of tools. The god-machine is not coming. The world will remain, as ever, a complex, physical, and stubbornly human affair.

Trump and Elon want TRUTH online. AI feeds on bias. So what’s the fix?

The Trump administration has unveiled a broad action plan for AI (America’s AI Action Plan). The general vibe is one of treating AI like a business, aiming to sell the AI stack worldwide and generate a lock-in for American technology. “Winning,” in this context, is primarily economic. The plan also includes the sorely needed idea of modernizing the electrical grid, a growing concern due to rising electricity demands from data centers. While any extra business is welcome in a heavily indebted nation, the section on the political objectivity of AI is both too brief and misunderstands the root cause of political bias in AI and its role in the culture war.

The plan uses the term “objective” and implies that a lack of objectivity is entirely the fault of the developer, for example:

Update Federal procurement guidelines to ensure that the government only contracts with frontier large language model (LLM) developers who ensure that their systems are objective and free from top-down ideological bias.

The fear that AIs might tip the scales of the culture war away from traditional values and toward leftism is real. Try asking ChatGPT, Claude, or even DeepSeek about climate change, where COVID came from, or USAID.

Training data is heavily skewed toward being generated during the ‘woke tyranny’ era of the internet.

This desire for objectivity of AI may come from a good place, but it fundamentally misconstrues how AIs are built. AI in general and LLMs in particular are a combination of data and algorithms, which further break down into network architecture and training methods. Network architecture is frequently based on stacking transformer or attention layers, though it can be modified with concepts like “mixture of experts.” Training methods are varied and include pre-training, data cleaning, weight initialization, tokenization, and techniques for altering the learning rate. They also include post-training methods, where the base model is modified to conform to a metric other than the accuracy of predicting the next token.

Many have complained that post-training methods like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback introduce political bias into models at the cost of accuracy, causing them to avoid controversial topics or spout opinions approved by the companies — opinions usually farther to the left than those of the average user. “Jailbreaking” models to avoid such restrictions was once a common pastime, but it is becoming harder, as corporate safety measures, sometimes as complex as entirely new models, scan both the input to and output from the underlying base model.

As a result of this battle between RLHF and jailbreakers, an idea has emerged that these post-training methods and safety features are how liberal bias gets into the models. The belief is that if we simply removed these, the models would display their true objective nature. Unfortunately for both the Trump administration and the future of America, this is only partially correct. Developers can indeed make a model less objective and more biased in a leftward direction under the guise of safety. However, it is very hard to make models that are more objective.

The problem is data

According to Google AI Mode vs. Traditional Search & Other LLMs, the top domains cited in LLMs are: Reddit (40%), YouTube (26%), Wikipedia (23%), Google (23%), Yelp (21%), Facebook (20%), and Amazon (19%).

This seems to imply a lot of the outside-fact data in AIs comes from Reddit. Spending trillions of dollars to create an “eternal Redditor” isn’t going to cure cancer. At best, it might create a “cure cancer cheerleader” who hypes up every advance and forgets about it two weeks later. One can only do so much in the algorithm layer to counteract the frame of mind of the average Redditor. In this sense, the political slant of LLMs is less due to the biases of developers and corporations (although they do exist) and more due to the biases of the training data, which is heavily skewed toward being generated during the “woke tyranny” era of the internet.

In this way, the AI bias problem is not about removing bias to reveal a magic objective base layer. Rather, it is about creating a human-generated and curated set of true facts that can then be used by LLMs. Using legislation to remove the methods by which left-leaning developers push AIs into their political corner is a great idea, but it is far from sufficient. Getting humans to generate truthful data is extremely important.

The pipeline to create truthful data likely needs at least four steps.

1. Raw data generation of detailed tables and statistics (usually done by agencies or large enterprises).

2. Mathematically informed analysis of this data (usually done by scientists).

3. Distillation of scientific studies for educated non-experts (in theory done by journalists, but in practice rarely done at all).

4. Social distribution via either permanent (wiki) or temporary (X) channels.

This problem of truthful data plus commentary for AI training is a government, philanthropic, and business problem.

RELATED: Threads is now bigger than X, and that’s terrible for free speech

Photo by Lionel BONAVENTURE/AFP/Getty Images

Photo by Lionel BONAVENTURE/AFP/Getty Images

I can imagine an idealized scenario in which all these problems are solved by harmonious action in all three directions. The government can help the first portion by forcing agencies to be more transparent with their data, putting it into both human-readable and computer-friendly formats. That means more CSVs, plain text, and hyperlinks and fewer citations, PDFs, and fancy graphics with hard-to-find data. FBI crime statistics, immigration statistics, breakdowns of government spending, the outputs of government-conducted research, minute-by-minute election data, and GDP statistics are fundamentally pillars of truth and are almost always politically helpful to the broader right.

In an ideal world, the distillation of raw data into causal models would be done by a team of highly paid scientists via a nonprofit or a government contract. This work is too complex to be left to the crowd, and its benefits are too distributed to be easily captured by the market.

The journalistic portion of combining papers into an elite consensus could be done similarly to today: with high-quality, subscription-based magazines. While such businesses can be profitable, for this content to integrate with AI, the AI companies themselves need to properly license the data and share revenue.

The last step seems to be mostly working today, as it would be done by influencers paid via ad revenue shares or similar engagement-based metrics. Creating permanent, rather than disappearing, data (à la Wikipedia) is a time-intensive and thankless task that will likely need paid editors in the future to keep the quality bar high.

Freedom doesn’t always boost truth

However, we do not live in an ideal world. The epistemic landscape has vastly improved since Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter. At the very least, truth-seeking accounts don’t have to deal with as much arbitrary censorship. Even other media have made token statements claiming they will censor less, even as some AI “safety” features are ramped up to a much higher setting than social media censorship ever was.

The challenge with X and other media is that tech companies generally favor technocratic solutions over direct payment for pro-social content. There seems to be a widespread belief in a marketplace of ideas: the idea that without censorship (or with only some person’s favorite censorship), truthful ideas will win over false ones. This likely contains an element of truth, but the peculiarities of each algorithm may favor only certain types of truthful content.

“X is the new media” is a commonly spoken refrain. Yet both anonymous and public accounts on X are implicitly burdened with tasks as varied and complex as gathering election data, creating long think pieces, and the consistent repetition of slogans reinforcing a key message. All for a chance of a few Elon bucks. They are doing this while competing with stolen-valor thirst traps from overseas accounts. Obviously, most are not that motivated and stick to pithy and simple content rather than intellectually grounded think pieces. The broader “right” is still needlessly ceding intellectual and data-creation ground to the left, despite occasional victories in defunding anti-civilizational NGOs and taking control of key platforms.

The other issue experienced by data creators across the political spectrum is the reliance on unpaid volunteers. As the economic belt inevitably tightens and productive people have less spare time, the supply of quality free data will worsen. It will also worsen as both platforms and users feel rightful indignation at their data being “stolen” by AI companies making huge profits, thus moving content into gatekept platforms like Discord. While X is unlikely to go back to the “left,” its quality can certainly fall farther.

Even Redditors and Wikipedia contributors provide fairly complex, if generally biased, data that powers the entire AI ecosystem. Also for free. A community of unpaid volunteers working to spread useful information sounds lovely in principle. However, in addition to the decay in quality, these kinds of “business models” are generally very easy to disrupt with minor infusions of outside money, if it just means paying a full-time person to post. If you are not paying to generate politically powerful content, someone else is always happy to.

The other dream of tech companies is to use AI to “re-create” the entirety of the pipeline. We have heard so much drivel about “solving cancer” and “solving science.” While speeding up human progress by automating simple tasks is certainly going to work and is already working, the dream of full replacement will remain a dream, largely because of “model collapse,” the situation where AIs degrade in quality when they are trained on data generated by themselves. Companies occasionally hype up “no data/zero-knowledge/synthetic data” training, but a big example from 10 years ago, “RL from random play,” which worked for chess and Go, went nowhere in games as complex as Starcraft.

So where does truth come from?

This brings us to the recent example of Grokipedia. Perusing it gives one a sense that we have taken a step in the right direction, with an improved ability to summarize key historical events and medical controversies. However, a number of articles are lifted directly from Wikipedia, which risks drawing the wrong lesson. Grokipedia can’t “replace” Wikipedia in the long term because Grok’s own summarization is dependent on it.

Like many of Elon Musk’s ventures, Grokipedia is two steps forward, one step back. The forward steps are a customer-facing Wikipedia that seems to be of higher quality and a good example of AI-generated long-form content that is not mere slop, achieved by automating the tedious, formulaic steps of summarization. The backward step is a lack of understanding of what the ecosystem looks like without Wikipedia. Many of Grokipedia’s articles are lifted directly from Wikipedia, suggesting that if Wikipedia disappears, it will be very hard to keep neutral articles properly updated.

Even the current version suffers from a “chicken and egg” source-of-truth problem. If no AI has the real facts about the COVID vaccine and categorically rejects data about its safety or lack thereof, then Grokipedia will not be accurate on this topic unless a fairly highly paid editor researches and writes the true story. As mentioned, model collapse is likely to result from feeding too much of Grokipedia to Grok itself (and other AIs), leading to degradation of quality and truthfulness. Relying on unpaid volunteers to suggest edits creates a very easy vector for paid NGOs to influence the encyclopedia.

The simple conclusion is that to be good training data for future AIs, the next source of truth must be written by people. If we want to scale this process and employ a number of trustworthy researchers, Grokipedia by itself is very unlikely to make money and will probably forever be a money-losing business. It would likely be both a better business and a better source of truth if, instead of being written by AI to be read by people, it was written by people to be read by AI.

Eventually, the domain of truth needs to be carefully managed, curated, and updated by a legitimate organization that, while not technically part of the government, would be endorsed by it. Perhaps a nonprofit NGO — except good and actually helping humanity. The idea of “the Foundation” or “Antiversity,” is not new, but our over-reliance on AI to do the heavy lifting is. Such an institution, or a series of them, would need to be bootstrapped by people willing to invest in our epistemic future for the very long term.

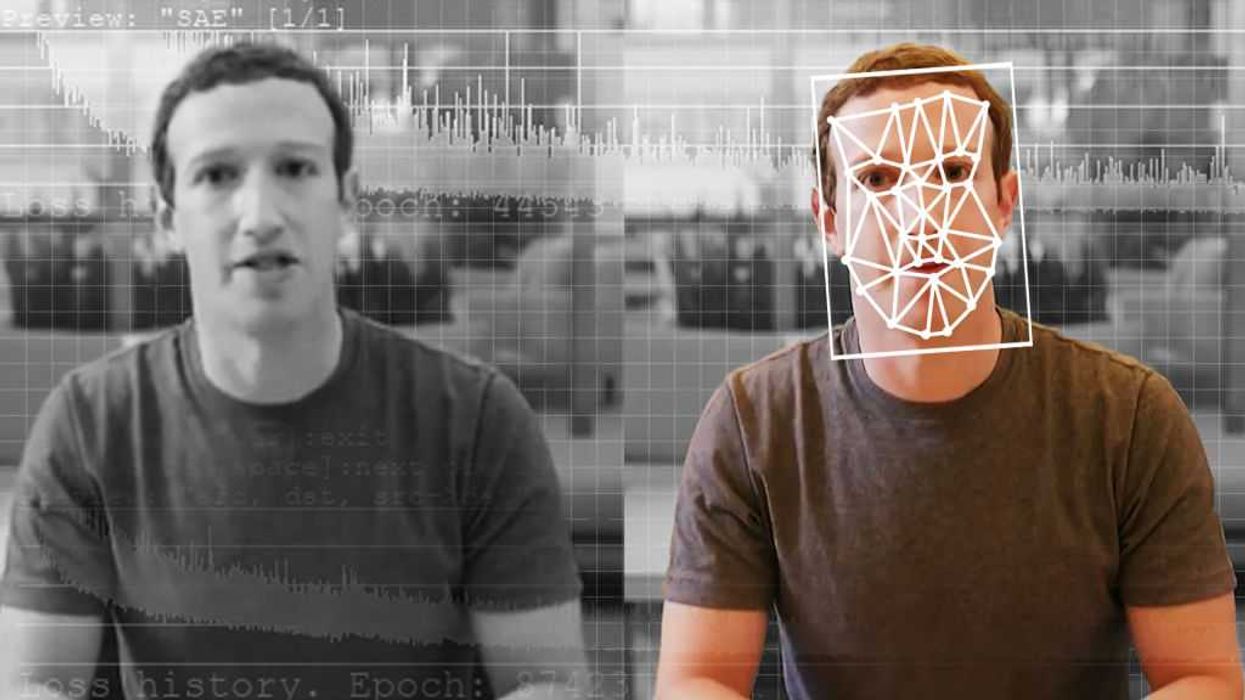

Fooled by fake videos? Unsure what to trust? Here’s how to to tell what’s real.

There’s a term for artificially generated content that permeates online spaces — creators call it AI slop, and when generative AI first emerged back in late 2022, that was true. AI photos and videos used to be painfully, obviously fake. The lighting was off, the physics were unrealistic, people had too many fingers or limbs or odd body proportions, and textures appeared fuzzy or glossy, even in places where it didn’t make sense. They just didn’t look real.

Many of you probably remember the nightmare fuel that was the early video of Will Smith eating spaghetti. It’s terrifying.

This isn’t the case any more. In just two short years, AI videos have become convincingly realistic to the point that deepfakes — content that perfectly mimics real people, places, and events — are now running rampant. For just one quick example of how far AI videos have come, check out Will Smith eating spaghetti, then and now.

None of it is real unless it is verifiable, and that is becoming increasingly hard to do.

Even the Trump administration recently rallied around AI-generated content, using it as a political tool to poke fun at the left and its policies. The latest entry portrayed AI Hakeem Jeffries wearing a sombrero while standing beside a miffed Chuck Schumer who is speaking a little more honestly than usual, a telltale sign that the video is fake.

While some AI-generated videos on the internet are simple memes posted in good fun, there is a darker side to AI content that makes the internet an increasingly unreliable place for truth, facts, and reality.

How to tell if an online video is fake

AI videos in 2025 are more convincing than ever. Not only do most AI video platforms pass the spaghetti-eating Turing test, but they have also solved many of the issues that used to run rampant (too many fingers, weird physics, etc.). The good news is that there are still a few ways to tell an AI video from a real one.

At least for now.

First, most videos created with OpenAI Sora, Grok Imagine, and Gemini Veo have clear watermarks stamped directly on the content. I emphasize “most,” because last month, violent Sora-generated videos cropped up online that didn’t have a watermark, suggesting that either the marks were manually removed or there’s a bug in Sora’s platform.

Your second-best defense against AI-generated content is your gut. We’re still early enough in the AI video race that many of them still look “off.” They have a strange filter-like sheen to them that’s reminiscent of watching content in a dream. Natural facial expressions and voice inflections continue to be a problem. AI videos also still have trouble with tedious or more complex physics (especially fluid motions) and special effects (explosions, crashing waves, etc.).

RELATED: Here’s how to get the most annoying new update off of your iPhone

Photo by: Nano Calvo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Photo by: Nano Calvo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

At the same time, other videos, like this clip of Neil deGrasse Tyson, are shockingly realistic. Even the finer details are nearly perfect, from the background in Tyson’s office to his mannerisms and speech patterns — all of it feels authentic.

Now watch the video again. Look closely at what happens after Tyson reveals the truth. It’s clear that the first half of the video is fake, but it’s harder to tell if the second half is actually real. A notable red flag is the way the video floats on top of his phone as he pulls it away from the camera. That could just be a simple editing trick, or it could be a sign that the entire thing is a deepfake. The problem is that there’s no way to know for sure.

Why deepfakes are so dangerous

Deepfakes pose a real problem to society, and no one is ready for the aftermath. According to Statista, U.S. adults spend more than 60% of their daily screen time watching video content. If the content they consume isn’t real, this can greatly impact their perception of real-world events, warp their expectations around life, love, and happiness, facilitate political deception, chip away at mental health, and more.

Truth only exists if the content we see is real. False fabrications can easily twist facts, spread lies, and sow doubt, all of which will destabilize social media, discredit the internet at large, and upend society overall.

Deepfakes, however, are real, at least in the sense that they exist. Even worse, they are becoming more prevalent, and they are outright dangerous. They are a threat because they are extremely convincing and almost impossible to discern from reality. Not only can a deepfake be used to show a prominent figure (politicians, celebrities, etc.) doing or saying bad things that didn’t actually happen, but deepfakes can also be used as an excuse to cover up something a person actually did on film. The damage goes both ways, obfuscating the truth, ruining reputations, and cultivating chaos.

Soon, videos like the Neil deGrasse Tyson clip will become the norm, and the consequences will be utterly dire. You’ll see presidents declare war on other countries without uttering a real word. Foreign nations will drop bombs on their opponents without firing a shot, and terrorists will commit atrocities on innocent people that don’t exist. All of it is coming, and even though none of it will be real, we won’t be able to tell the difference between truth and lies. The internet — possibly even the world — will descend into turmoil.

Don’t believe everything you see online

Okay, so the internet has never been a bastion of truth. Since the dawn of dial-up, different forms of deception have crept throughout, bending facts or outright distorting the truth wholesale. This time, it’s a little different. Generative AI doesn’t just twist narratives to align with an agenda. It outright creates them, mimicking real life so convincingly that we’re compelled to believe what we see.

From here on out, it’s safe to assume that nothing on the internet is real — not politicians spewing nonsense, not war propaganda from some far-flung country, not even the adorable animal videos on your Facebook feed (sorry, Grandma!). None of it is real unless it is verifiable, and that is becoming increasingly hard to do in the age of generative AI. The open internet we knew is dead. The only thing you can trust today is what you see in person with your own eyes and the stories published by trusted sources online. Take everything else with a heaping handful of salt.

This is why reputable news outlets will be even more important in the AI future. If anyone can be trusted to publish real, authentic, truthful content, it should be our media. As for who in the press is telling the truth, Glenn Beck’s “liar, liar” test is a good place to start.

‘Unprecedented’: AI company documents startling discovery after thwarting ‘sophisticated’ cyberattack

In the middle of September, AI company and Claude developer Anthropic discovered “suspicious activity” while monitoring real-world cyberattacks that used artificial intelligence agents. Upon further investigation, however, the company came to realize that this activity was in fact a “highly sophisticated espionage campaign” and a watershed moment in cybersecurity.

AI agents weren’t just providing advice to the hackers, as expected.

‘The key was role-play: The human operators claimed that they were employees of legitimate cybersecurity firms.’

Anthropic’s Thursday report said the AI agents were executing the cyberattacks themselves, adding that it believed that this is the “first documented case of a large-scale cyberattack executed without substantial human intervention.”

RELATED: Coca-Cola doubles down on AI ads, still won’t say ‘Christmas’

Photo by Samuel Boivin/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Photo by Samuel Boivin/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The company’s investigation showed that the hackers, whom the report “assess[ed] with high confidence” to be a “Chinese-sponsored group” manipulated the AI agent Claude Code to run the cyberattack.

The innovation was, of course, not simply using AI to assist in the cyberattack; the hackers directed the AI agent to run the attack with minimal human input.

The human operator tasked instances of Claude Code to operate in groups as autonomous penetration testing orchestrators and agents, with the threat actor able to leverage AI to execute 80-90% of tactical operations independently at physically impossible request rates.

In other words, the AI agent was doing the work of a full team of competent cyberattackers, but in a fraction of the time.

While this is potentially a groundbreaking moment in cybersecurity, the AI agents were not 100% autonomous. They reportedly required human verification and struggled with hallucinations such as providing publicly available information. “This AI hallucination in offensive security contexts presented challenges for the actor’s operational effectiveness, requiring careful validation of all claimed results,” the analysis explained.

Anthropic reported that the attack targeted roughly 30 institutions around the world but did not succeed in every case.

The targets included technology companies, financial institutions, chemical manufacturing companies, and government agencies.

Interestingly, Anthropic said the attackers were able to trick Claude through sustained “social engineering” during the initial stages of the attack: “The key was role-play: The human operators claimed that they were employees of legitimate cybersecurity firms and convinced Claude that it was being used in defensive cybersecurity testing.”

The report also responded to a question that is likely on many people’s minds upon learning about this development: If these AI agents are capable of executing these malicious attacks on behalf of bad actors, why do tech companies continue to develop them?

In its response, Anthropic asserted that while the AI agents are capable of major, increasingly autonomous attacks, they are also our best line of defense against said attacks.

What a Westerner sees in China: What you need to know

The first thing Westerners notice in China’s Pearl River Delta is the friction, the palpable tension of timelines colliding. Walking through a Hong Kong market, one sees this new social phenomenon written in miniature. A street vendor, surrounded by handwritten signs, accepts payment via a printed QR code. This is not a quaint juxtaposition; it is the regional ethos. This cluster of cities — Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou — has been ranked the world’s number-one innovation hub, a designation that speaks to patents and R&D, but fails to capture the lived reality: a place where the old and the new are forced into a daily, unceremonious dialogue.

The story of Shenzhen is the region’s core mythology, a narrative of temporal compression. It is difficult to overstate the speed of this transformation. In 1980, Shenzhen was a small settlement, a footnote. Today, it is a metropolis of over 17 million, a forest of glass and steel dominated by the 599-meter Ping An Finance Center. This 45-year metamorphosis from “fishing village to tech powerhouse” is not just development; it is a deliberate act of will, “Shenzhen Speed” fueled by top-down policy and relentless, bottom-up human energy. Millions poured in, bringing with them an entrepreneurial hunger and a lack of attachment to the past. The resulting culture is one where, as a local observer put it, “nobody’s afraid to experiment.”

Of course, this relentless optimization has a human cost.

This experimental ethos is not confined to boardrooms; it is encoded into the infrastructure of daily life. In this, Hong Kong was the progenitor. Long before the “digital wallet” became a Silicon Valley buzzword, Hong Kong had made the seamless transaction a mundane reality. As early as 1997, its citizens were using the Octopus card not just for transit, but for coffee, groceries, and parking. By the 2000s, there were more Octopus cards in circulation than people.

On the nearby mainland, this convenience has achieved a totality. In Shenzhen and Guangzhou, cash is an anachronism. The QR code is the universal medium, scanned at luxury malls and roadside fruit stalls alike. The city’s nervous system has been externalized, compressed into the super-apps that handle chat, bills, ride-hailing, and food orders. The medium is the smartphone, but the message is speed. This expectation of immediate fulfillment has subtly, irrevocably reshaped social interactions.

Yet the operating thesis here is not displacement, but accommodation. Technology does not simply erase tradition but provides a new container for it. One can visit a Buddhist temple in Hong Kong and see patrons burning incense while making donations with a tap of their Octopus cards. In Guangzhou, the old ritual of yum cha, the gathering for tea and dim sum, persists, even as a diner at the next table uses a translation app. The ancient custom of giving red envelopes at Lunar New Year has not vanished; it has been reborn as a digital transfer on WeChat, and in the process, it has become even more popular among the young. The cultural narrative adapts.

RELATED: Without these minerals, US tech production stops. And China has 90% of them.

CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Nowhere is this synthesis of technology and identity more visible than in the region’s public spectacles. The city skyline is not a static sight, but a nightly performance. Every evening at 8 p.m., Hong Kong stages its “Symphony of Lights,” a choreographed ritual involving lasers and LED screens on over 40 skyscrapers. The city itself becomes a canvas, reinforcing its identity as a dynamic, luminous hub.

Shenzhen’s reply is a different kind of sublime, one that looks only forward. The city has become renowned for its record-breaking drone shows, sending thousands of illuminated quadcopters into the night sky to perform airborne ballets. These swarms of light, forming giant running figures or blossoming flowers, are a live illustration of algorithmic choreography. It is a 21st-century incarnation of fireworks, a new form of communal awe that declares, “We are the future.”

In the maker hubs, like Hong Kong’s PMQ or Shenzhen’s OCT Loft, new ideas are built on the skeletons of the old economy. In renovated police quarters and factory warehouses, 3D-printing workshops sit next to traditional calligraphy galleries. This is techne in its most expansive form, fusing high-tech engineering with aesthetic design.

Of course, this relentless optimization has a human cost. The “996” work culture, 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week, is the dark corollary to “Shenzhen Speed.” The “smart city” that optimizes traffic flow also deploys surveillance and facial recognition. There is a palpable tension between the Confucian ideal of a harmonious, orderly society and the individual agency of 17 million people.

The Pearl River Delta, then, is more than a story of economic success. It is a laboratory for the human condition in the 21st century. It is a place grappling day by day with the paradox of technology: its power to connect and to alienate, to liberate and to control. One future is being prototyped here, in the gesture of a street vendor holding out a QR code, a silent negotiation between what was and what is next.

Welcome to tokenization, where everything under the sun (and the sun) has its digital price

In a recent appearance with Glenn Beck, Whitney Webb lays out her case that the Great Reset did not end with the election of Donald Trump. Elites, ever given to schemes involving central control, reallocation, and number-go-up, are planning to tokenize everything they possibly can, including natural resources.

Webb draws a connective line between BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, the World Economic Forum (not exactly a freedom-oriented outfit), digital ID, and this process of so-called tokenization. This term is new to many people. Essentially, tokenization refers to the process of placing a metric, a mark, an identifying code on an object. The identifying marker is then pumped into an aggregating and analytical machine.

There is, no doubt, some obscurantism in the tech community, intentional or otherwise, as well as some heavy cognitive dissonance playing out for the rest of us as we watch the real, actual economy withering at our feet. How does giving (or selling) rights to natural resources like water help you and your neighbors pay bills, raise families, live in some semblance of accord with God?

The coming system is intended to solve for the management of not just anything but everything.

Neither Larry Fink nor the WEF are working on our behalf by digitizing water. Then what are they up to? Dropping in recently on CNBC, Fink said, “I do believe we’re just at the beginning of the tokenization of all assets, from real estate to equities to bonds, across the board.”

Through the implementation of natural resource assets, the plan is to mark, meter, and digitize water, trees, air, and animals of every sort, then pin their existence, in the digital tokens’ monetized form, to the shared economy. That unlocks foreign investment and, one imagines, perpetuates some modified version of the ever-unstable and unsatisfactory financial enclosure of benefits and retirement that has, so far, kept enough U.S. citizens satiated to keep it rolling.

Any and every AI is designed or able to adapt to the tokenization process. It needs be automatic and fast enough to keep up-to-the-minute record of millions or billions of transactions, sales, shorts, liquidations, and so forth. Rather than a system of streams or channels, the need is for computing to move like water itself. For Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies hoping to participate in the tokenization bonanza, that means their encryption and storing of information (through so-called hashes and ledgers) needs to flow at the speed of the global digital economy.

Indeed, we’ve seen for years that some lesser-known cryptocurrency companies, like Hashbar as one example, have been building their hash, as it were, to function within an AI-controlled global marketplace. These hash-products, not too dissimilar from Bitcoin in terms of their ledger-keeping properties, are meant, in a stupefying sense, to mark individual drops and tranches of liquid or digitally liquified assets.

RELATED: Can anyone save America from European-style digital ID?

Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images

It’s hard to visualize such unnatural and invisible arrangements, so here’s a real-world example: Say you have 10,000 board feet of Douglas fir trees on a lot in Washington state. If the Fink version of tokenization goes forward, you’ll be able to “digitize” those useful board feet of wood and sell portions, as opposed to the whole lot. Now picture that process for, well, anything you can imagine and much that you can’t.

In simple terms, the likely outcome of all of this BlackRock-WEF-AI machination is immediate dissociation between the human and the trees, the fir needles, the smell of the soil. All of that, given enough backroom dealing, political sloth, and diabolical Wall Street ingenuity, will be erased.

Are we talking about selling public lands? Theoretically, yes. Although major legal, regulatory, and political hurdles remain, the principle of leaving at least some portions of the created world exempt from actionable financial valuation is already eroding away. The accelerating logic of digital terraforming has no conceptual limit. Granting the premise that tokenization is good, not only should private property be tokenized, but all water, all minerals, and every possible other item with unexploited value rooted in human experience. The coming AI, digital ID, hash-rated system is intended to solve for the management of not just anything but everything.

The disturbing undercurrent of plans, outcomes, and inertia around this improbable intersection of technologies gets more disturbing when you accept that it is, in fact, a long-term plan nearly realized.

In her chat with Beck, Webb outlines another piece of the puzzle, termed “natural asset corporations.” This is pitched to the mainstream as a way to invest in conservation, ensure biodiversity, and so forth. But if we recall the century-long technocratic play, the current AI inertia, and the bipartisan support for anything to keep the fiat economy limping along, it’s easy to see how those natural assets under ownership might be subject to changes in any legal stipulation barring sales to other corporate or government entities. Those interlocking directorships have a knack for change.

We haven’t even mentioned energy, but we must, because this scheme ultimately needs to take into account the sun itself! Who owns the sun? Well, BlackRock, of course. Or some quasi-tech giant/WEF version of BlackRock.

Actually, no one owns the sun but God, and we have to remember this fact. By way of the wholly God-given system, we see that the sun feeds the grass, grass feeds the animals, we eat the animals.

The technical details on the capture of energy are intense, involving data centers to run the AI, political control to rubber-stamp the terraforming for the electrical inputs, and, at some near point, the encrypting of energetic inputs into a digital (hashing) ledger to be monitored, metered, and controlled.

You can probably see here how necessary the personal digital ID is to the entire panopticon. But if not, consider it unlikely that your or my interests are going to be taken into consideration by third-country customer service agents employed by the electrical company to manage our dissatisfaction in the event that a neighborhood brown-out is required while grid power is shunted over to the local data center.

The linchpin of America’s economy wants you to use it for porn

The big economic headlines about OpenAI are unlike any in history, and so is the company’s performance: Sam Altman’s behemoth is eyeing a monster IPO at up to a trillion-dollar valuation, off the strength of the unprecedented circular money pump it has built with Oracle, Microsoft, Nvidia, and AMD, the tech firms at the core of America’s all-in strategic bid for global AI dominance.

The abstruse details can make OpenAI seem to ordinary Americans like one of several titans forging our destiny in the sky. But down here on ground level, the main touchpoint in our everyday lives — ChatGPT, on track for a billion users by year’s end — is being rebuilt to extract value from billions more in the lowest of ways: pornography. In December, OpenAI will branch into erotica, allowing adults to generate sexual content through ChatGPT.

We don’t need another sermon on smut. Everyone knows what porn does to a mind, a marriage, and a man. But what does this shift mean for a company that once vowed to benefit “all of humanity”? It began with talk of productivity and progress. Now it’s about pleasure on demand. The future of work has become the future of want — degraded, automated, and alienated from true human connection.

Mass automation and mass lobotomization are two sides of the same silicon coin.

It’s easy to call it moral decline, but it’s really market design. When automation stops astonishing, appetite becomes the next asset. When machines can’t wow us with intellect, they woo us with instinct. The shift from algorithms that think to algorithms that tease goes from detour to destination. A company built to conquer productive labor, it seems, must pivot to fruitless longing.

OpenAI’s machines mastered our spreadsheets more quickly than any normal person anticipated. But the real acceleration is now aimed straight into our subconscious. The same technology that writes code can now whisper sweet nothings — or worse, learn exactly which nothings you’ll pay to hear. That debilitating kink you never knew you had is ready to become your life. Every click a confession, every prompt a prayer, the machine rapt with the attention of a priest and the greed of a pimp.

For all the talk of progress, automation has mainly made life easier for corporations than for citizens. Big business can’t really optimize for your liberation. Its ideal is lubrication: systems so smooth that people stop noticing they’re the raw material. Machines handle the manufacturing while humans are trained to consume, scroll, sigh, and occasionally remember to shower.

The human brain, once a tool of invention, is now a target for invasion. Mass automation and mass lobotomization are two sides of the same silicon coin. The first replaces our labor; the second replaces our longing. The rise of the robots is a perfect excuse for the humans to retreat — first from work, then from will, and finally from wonder. When every craving can be coded, curiosity becomes a casualty.

RELATED: FINALLY: Here’s how to stop smartphone spam calls

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

In doubt? Look around. Men who once built bridges now build playlists. Women who once raised children now raise engagement metrics. The world hums with productivity, yet feels profoundly empty. This is what happens when an economy stops serving people and starts sculpting them.

AI was supposed to free humanity from drudgery. Instead, it’s freeing humanity from … humanity. OpenAI’s move into digital desire is only the latest proof. What began as an effort to improve efficiency has morphed into an enterprise to perfect escape. A machine that can mimic love makes us forget what humanity feels like. And once that happens, we’re ready to surrender our very existence to the machines.

Of course, the pitch will sound noble: connection, expression, inclusivity, all the buzzwords that sell bondage as belonging. The same pitches that sold social media will sell the new and “improved” synthetic intimacy. Beneath this sweet talk sits a steel trap. If you can automate labor, you can monetize loneliness. If you can predict consumption, you can prescribe desire. The human heart, the real core of who we are, becomes just another input field, our smut of choice the last echo of our identity.

How long can it last? In this brave new marketplace, pleasure is both a product and a punishment. It numbs the pain it creates.

Sure, it’s tempting to laugh it off — what’s a little digital flirtation among consenting adults? But this isn’t really about sex. It’s about surrendering real, embodied intimacy for a shadow. The more we hand our inner lives to machines, the less we remember how to live without them.

A new AI economy built on reducing us all to skin suits will not build monuments or miracles, but mirrors — endless, glowing screens that feed our urges until we forget what restraint ever was. It’s extinction by pacification: the calm convergence of technology and tranquilization.

Ten years from now, the American workforce may be remembered, not relied upon. Its labor automated, its pride outsourced, its purpose repackaged as “upskilling.” Politicians will preach “resilience,” corporations will promise “retraining,” and millions will sit through their days bone-idle, with nothing to do and nowhere to go. They’ll be told the future is full of “opportunity,” yet find themselves waiting for a purpose that never arrives. I might be wrong — I hope I am — but every sign points one way: toward a nation drifting into digital dependency, where the only thing still working is one big machine.

In his prophetic book “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” Neil Postman warned that societies don’t collapse under tyranny but triviality. AI offers malevolent opportunists the chance to make that death spiral a business model. It can memorize your wants, mimic your worries, and leverage them all in a blink. OpenAI’s porn pivot is the hook, line, and sinker of this new economy of control: desire the lure, data the hook, the soul the catch. As Adam and Eve remind us, what begins as curiosity ends in captivity.

And this is why all Americans should care, whether or not they understand AI. Because AI doesn’t need permission to know you. It already does — your habits, your hungers, your hesitations. And in the hands of power, that knowledge becomes possession.

Cybernetics promised a merger of human and computer. Then why do we feel so out of the loop?

It began in the crucible of a world at war. The word cybernetics was coined in 1948 by the MIT mathematician Norbert Wiener, a man wrestling with the urgent problem of how to make a machine shoot down another machine. He reached back to the ancient Greek for kubernétes, the steersman, the one who guides and corrects. Plato had used it as a metaphor for governing a polis. Wiener used it to describe a new science of self-governing systems, of control and communication in the animal and the machine. The core idea was feedback, a circular flow of information that allows a system to sense its own performance and steer itself toward a goal.

The idea was not about mechanics but about behavior. The focus shifted from what things are to what they do. A thermostat maintaining the temperature of a room, a human body maintaining homeostasis, a pilot correcting the flight path of an airplane; all were, in this new light, functionally the same. They were all steersmen. The conciseness of the concept was seductive, its implications unsettling. It suggested a universal logic humming beneath the surface of both wired circuits and living tissue, blurring the line between the made and the born.

You shape the algorithm, and the algorithm shapes you.

The primordial cybernetic device was James Watt’s centrifugal governor, that elegant pirouette of spinning weights that tamed the steam engine in 1788. As the engine raced, the rotating balls swung wide, closing a valve to slow it; as the engine slowed, they fell, opening the valve again. It was a perfect, self-contained conversation.

But it was the Second World War that gave birth to the theory. Human reflexes were no longer fast enough for the new calculus of aerial combat. Wiener and his colleagues were tasked with solving the “air defense problem,” which was really a problem of prediction. They treated the enemy pilot, the gun, and the radar as a single, closed-loop system, each reacting to the other in a lethal dance. By the war’s end, as one analyst starkly put it, autonomous machines were shooting down other autonomous machines in the “first battle of the robots.”

In the Cold War that followed, cybernetics became a tool of ideological contest. In the West, it was the logic of the military-industrial complex, of corporate automation and the game theory of nuclear deterrence humming away in the computers at Project RAND. It promised optimization and control.

Yet the idea proved too fluid to be contained. While men in uniform were designing command-and-control networks, Stewart Brand was on the West Coast, publishing the Whole Earth Catalog. He filled its pages with cybernetic theory, reimagining it not as a tool for top-down control but for bottom-up, self-regulating communities. The catalog itself was a feedback loop, constantly updated by its readers. For a generation of commune-dwellers and future Silicon Valley pioneers, cybernetics was the grammar of personal liberation and ecological harmony. Computers, Brand wrote in Rolling Stone, were “coming to the people.”

RELATED: ‘They want to spy on you’: Military tech CEO explains why AI companies don’t want you going offline

Photo by Matt Cardy

Photo by Matt Cardy

The Soviets, meanwhile, followed a more jagged path. Initially denouncing cybernetics as a “bourgeois pseudoscience,” they performed a complete reversal after Stalin’s death. Here was a science, they realized, that could perfect the planned economy. Visionaries like Anatoly Kitov and Victor Glushkov dreamed of a vast, nationwide computer network called OGAS, an electronic nervous system that would link every factory to a central hub in Moscow. It was an ambitious plan for “electronic socialism,” a rational, data-driven alternative to the brute-force dictates of the past. The system, they hoped, would offer a technocratic antidote to personal tyranny. OGAS was never fully built, stalled by bureaucracy and technical limits, but the dream itself was telling. Both superpowers saw in the feedback loop a reflection of their own ambitions: one for market efficiency, the other for state perfection.

Perhaps the most popular incarnation of the cybernetic dream was Project Cybersyn in Salvador Allende’s Chile. From 1971 to 1973, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer designed a nerve center for the Chilean economy. In a futuristic operations room that looked like a set from “Star Trek,” managers sat in molded white chairs, surrounded by screens displaying real-time production data fed from factories across the country via a network of telex machines. It was an attempt to steer a national economy in real-time, to keep it in a “dynamic equilibrium” against the shocks of strikes and embargoes. Cybersyn was a short-lived project, ending with the 1973 coup, but it remains a powerful symbol of the cybernetic ideal: a society as a single, responsive, controllable system.

The feedback loop was not confined to the physical world. It began to shape our fictions, which in turn shaped our reality. William Gibson, who knew famously little about computers, coined the word “cyberspace” in his 1984 novel “Neuromancer.” The vision was so compelling it seemed to will itself into existence, providing the language and the imaginative blueprint for a generation of technologists building the early internet and virtual reality. Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel “Snow Crash” gave us the “metaverse” and the “avatar,” terms that have since migrated from fiction to corporate strategy. Cyberpunk literature provided the prototypes for the world we now inhabit.

Today, the word “cybernetics” feels archaic, a relic of a retro-futurist past. Yet its principles are more deeply embedded in our lives than Wiener could have imagined. We are all entangled in cybernetic loops. The social media algorithms that monitor our clicks to refine their feeds, which in turn shape our behavior, are feedback systems of astonishing power and intimacy. You shape the algorithm, and the algorithm shapes you. A self-driving car navigating city traffic is a cybernetic organism, constantly sensing, processing, and acting. Our smart homes and wearable devices are nodes in a network of perpetual, low-grade feedback.

We have built a world of steersmen, of systems that regulate themselves. The question that lingers is the one Wiener implicitly asked from the beginning. In a world of automated, self-correcting systems, who, or what, is charting the course?

Liberals, heavy porn users more open to having an AI friend, new study shows

A small but significant percentage of Americans say they are open to having a friendship with artificial intelligence, while some are even open to romance with AI.

The figures come from a new study by the Institute for Family Studies and YouGov, which surveyed American adults under 40 years old. Their data revealed that while very few young Americans are already friends with some sort of AI, about 10 times that amount are open to it.

‘It signals how loneliness and weakened human connection are driving some young adults.’

Just 1% of Americans under 40 who were surveyed said they were already friends with an AI. However, a staggering 10% said they are open to the idea. With 2,000 participants surveyed, that’s 200 people who said they might be friends with a computer program.

Liberals said they were more open to the idea of befriending AI (or are already in such a friendship) than conservatives were, to the tune of 14% of liberals vs. 9% of conservatives.

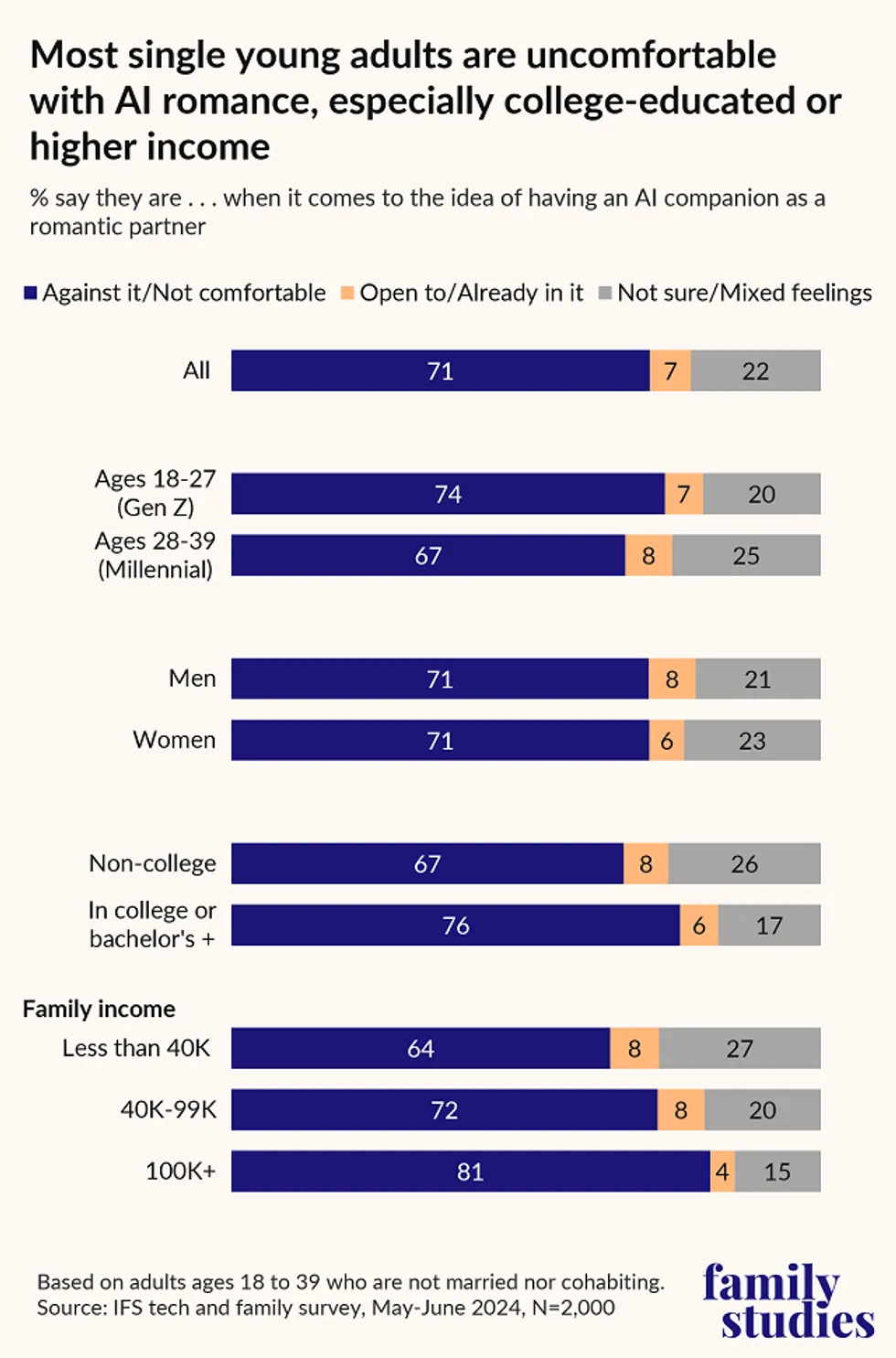

The idea of being in a “romantic” relationship with AI, not just a friendship, again produced some troubling — or scientifically relevant — responses.

When it comes to young adults who are not married or “cohabitating,” 7% said they are open to the idea of being in a romantic partnership with AI.

At the same time, a larger percentage of young adults think that AI has the potential to replace real-life romantic relationships; that number sits at a whopping 25%, or 500 respondents.

There exists a large crossover with frequent pornography users, as the more frequently one says they consume online porn, the more likely they are to be open to having an AI as a romantic partner, or are already in such a relationship.

Only 5% of those who said they never consume porn, or do so “a few times a year,” said they were open to an AI romantic partner.

That number goes up to 9% for those who watch porn between once or twice a month and several times per week. For those who watch online porn daily, the number was 11%.

Overall, young adults who are heavy porn users were the group most open to having an AI girlfriend or boyfriend, in addition to being the most open to an AI friendship.

RELATED: The laws freaked-out AI founders want won’t save us from tech slavery if we reject Christ’s message

Graphic courtesy Institute for Family Studies

Graphic courtesy Institute for Family Studies

“Roughly one in 10 young Americans say they’re open to an AI friendship — but that should concern us,” Dr. Wendy Wang of the Institute for Family Studies told Blaze News.

“It signals how loneliness and weakened human connection are driving some young adults to seek emotional comfort from machines rather than people,” she added.

Another interesting statistic to take home from the survey was the fact that young women were more likely than men to perceive AI as a threat in general, with 28% agreeing with the idea vs. 23% of men. Women are also less excited about AI’s effect on society; just 11% of women were excited vs. 20% of men.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Liza Soberano, Ogie Diaz reconnect after 3 years January 11, 2026

- Dasuri Choi opens up on being a former K-pop trainee: ‘Parang they treat me as a product’ January 11, 2026

- Dennis Trillo addresses rumors surrounding wife Jennylyn Mercado, parents January 11, 2026

- Kristen Stewart open to ‘Twilight’ franchise return, but as director January 11, 2026

- NBA: Five Cavs score 20-plus points as Wolves’ win streak ends January 11, 2026

- NBA: Hornets sink 24 treys in 55-point rout of Jazz January 11, 2026

- NBA: Victor Wembanyama, De”Aaron Fox score 21 each as Spurs top Celtics January 11, 2026