Day: November 2, 2025

Taxpayer cost for suspected Charlie Kirk assassin’s death penalty case predicted by Utah commissioner

Utah County faces mounting defense costs for Tyler Robinson’s case after local attorneys declined to represent the man accused of killing Charlie Kirk.

Trump admin responds to ‘Dilbert’ creator’s plea to ‘help save my life’ by expediting cancer treatment

“Dilbert” creator Scott Adams makes urgent plea to Trump for help getting cancer treatment after reported Kaiser Permanente scheduling delays.

DAVID MARCUS: In Harlem, excitement for Mamdani and a warning for Cuomo

NYC mayor race heats up in Harlem as Zohran Mamdani campaigns with youthful energy while Andrew Cuomo faces enthusiasm gap among black voters ahead of primary.

76ers’ Joel Embiid slams $50,000 fine over ‘lewd gesture’

Philadelphia 76ers star Joel Embiid slammed the NBA for the fine it issued after he did the WWE-style “crotch chop” in the first quarer against the Boston Celtics on Friday.

Dentist recommends four foods that protect teeth from holiday sweets

Protect your teeth after Halloween candy with these 4 “fantastic” foods. Apples, cheese, cranberries and pumpkin naturally fight cavities and strengthen enamel.

Bengals star makes incredible TD catch, achieves milestone only Hall of Famers accomplished

Cincinnati Bengals wide receiver Tee Higgins joined Jerry Rice and Cris Carter as the only receivers with a touchdown catch in nine consecutive home games.

Hamas hands over 3 deceased hostages to Red Cross, Israel says

Three deceased Israeli hostages’ bodies transferred to Israel through Red Cross after recovery operation in Gaza, with identification process underway.

Academia • Academics • Blaze Media • College • School • University

Coddled Harvard students cry after dean exposes grade inflation, ‘relaxed’ standards

Harvard University’s Office of Undergraduate Education released a 25-page report on Monday revealing that roughly 60% of the grades dished out in undergraduate classes are As. This is apparently not a signal that the students are necessarily better or smarter than past cohorts but rather that Harvard As are now easier to come by.

According to the report, authored by the school’s dean of undergraduate education Amanda Claybaugh and reviewed by the Harvard Crimson, the proportion of students receiving A grades since 2015 has risen by 20 percentage points.

‘If that standard is raised even more, it’s unrealistic to assume that people will enjoy their classes.’

Whereas at the time of graduation, the median grade point average for the class of 2015 was 3.64, it was 3.83 for the class of 2025 — and the Harvard GPA has been an A since the 2016-2017 academic year.

“Nearly all faculty expressed serious concern,” wrote Claybaugh. “They perceive there to be a misalignment between the grades awarded and the quality of student work.”

Citing responses from faculty and students, the report revealed that the specific functions of grading — motivating students, indicating mastery of subject matter, and separating the wheat from the chaff — are not being fulfilled.

RELATED: Harvard posts deficit of over $110 million as funding feud with Trump continues to sting

Photo by Zhu Ziyu/VCG via Getty Images

Photo by Zhu Ziyu/VCG via Getty Images

“In the view of faculty, grades currently distinguish between work that meets expectations or fails to meet expectations, but beyond that grades don’t distinguish much at all,” said the report. “‘Students know that an ‘A’ can be awarded,’ one faculty member observed, ‘for anything from outstanding work to reasonably satisfactory work. It’s a farce.'”

Claybaugh acknowledged that grades can serve as a useful and transparent way to “distinguish the strongest student work for the purposes of honors, prizes, and applications to professional and graduate schools.” However, since As are now handed out like candy and many students have identical GPAs, prizes and other benefits must now be dispensed on the basis of less objective factors, which “risks introducing bias and inconsistency into the process,” suggested the dean.

The report noted further that Harvard University’s current grading practices “are not only undermining the functions of grading; they are also damaging the academic culture of the College more generally” by constraining student choice, exacerbating stress, and “hollowing out academics.”

Steven McGuire, a fellow at the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, highlighted the admission in the report that Harvard owes much of its current crisis to its coddling of unprepared students.

“For the past decade or so, the College has been exhorting faculty to remember that some students arrive less prepared for college than others, that some are struggling with difficult family situations or other challenges, that many are struggling with imposter syndrome — and nearly all are suffering from stress,” said the report.

“Unsure how best to support their students, many have simply become more lenient. Requirements were relaxed, and grades were raised, particularly in the year of remote instruction,” continued the report. “This leniency, while well-intentioned, has had pernicious effects.”

The new report is hardly the first time the school has suggested that Harvard undergraduate students tend to be coddled, intellectually fragile, ideologically rigid, and slothful.

Citing faculty feedback, Harvard’s Classroom Social Compact Committee indicated in a January report that undergraduate students “have rising expectations for high grades, but falling expectations for effort”; often don’t attend class; frequently don’t do many of the assigned readings; seek out easy courses; and in some cases are “uncomfortable with curricular content that is not aligned with the student’s moral framework.”

The January report noted further that “some teaching fellows grade too easily because they fear negative student feedback.”

Claybaugh’s grade inflation report has reportedly prompted complaints and whining this week from students.

Among the dozens of students who objected to the report and its findings was Sophie Chumburidze, who told the Harvard Crimson, “The whole entire day, I was crying.”

“I skipped classes on Monday, and I was just sobbing in bed because I felt like I try so hard in my classes, and my grades aren’t even the best,” said Chumburidze. “It just felt soul-crushing.”

Kayta Aronson told the Crimson that higher standards could adversely impact students’ health.

“It makes me rethink my decision to come to the school,” said Aronson. “I killed myself all throughout high school to try and get into this school. I was looking forward to being fulfilled by my studies now, rather than being killed by them.”

Zahra Rohaninejad suggested that raising standards might sap the enjoyment out of the Harvard experience.

“I can’t reach my maximum level of enjoyment just learning the material because I’m so anxious about the midterm, so anxious about the papers, and because I know it’s so harshly graded,” said Rohaninejad. “If that standard is raised even more, it’s unrealistic to assume that people will enjoy their classes.”

The student paper indicated the university did not respond to its request for comment.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Blaze Media • Camera phone • Free • Upload • Video • Video phone

‘Franken-wheat’: The real reason Americans can’t eat bread anymore

Across the country, Americans have begun realizing they have a gluten sensitivity — but other countries don’t have the same issue. And according to Christian homesteader Michelle Visser, it’s not the fault of bread, but rather, how it’s made in America.

“Talking about other countries, back when we were adding into our flour and enriching it, other countries didn’t do that. In fact, in Italy, they had a pellagra outbreak around the same time that we were dealing with it here, but they responded completely different in little towns in Italy,” Visser tells BlazeTV host Allie Beth Stuckey.

“They literally built communal ovens, bread ovens, and they encouraged them to use good grains, which had not gone through the green revolution of our country … and make whole wheat bread,” she explains.

“They knew that it was related to folate, and they knew it was dietary, and they said, ‘What can we do? We have in these small towns a lot of poor people who can’t necessarily afford good food. So one thing is, let’s at least give them the equipment to make the bread,’” she continues.

And the result of this, Visser explains, was wiping out pellagra — which was attributed to spoiled bread and polenta.

“So do you think gluten is unfairly demonized?” Stuckey asks.

“I think it is,” Visser says, using Norman Borlaug, the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, as an example of being focused on the wrong issue when it comes to gluten.

“He had figured out how to manipulate wheat to give it a higher yield and to just simply grow more wheat for your buck. And while there’s definite advantages to understanding plant science, unfortunately, every time that we genetically change or we breed certain characteristics into any of our food, we are losing some nutrition,” she tells Stuckey.

“When they started milling it with the steel mills, they went from 20 barrels of flour a day to 500 barrels of flour a day with no extra energy, no extra expense. So there’s definitely money involved in the whole story is what I’m saying,” she explains.

“This bread that has been stripped of the good stuff, inserted with the synthetic stuff, that is maybe what’s causing the problems, especially in America,” Stuckey comments, surprised.

“Yeah,” Vasser confirms, noting that we’ve also added more protein into modern-day wheat, which has created a “franken-wheat.”

And then on top of what already is “franken-wheat,” wheat manufacturers have begun using pesticides and herbicides.

“If you are not buying organic flour, glyphosate is in trace amounts in your flour. It’s just, it’s there … if we are exposing our gut to glyphosate, we are killing the good bacteria. We’ve had gut problems in this country for many decades … and I think a lot of it has to do with this glyphosate in our flour.”

Want more from Allie Beth Stuckey?

To enjoy more of Allie’s upbeat and in-depth coverage of culture, news, and theology from a Christian, conservative perspective, subscribe to BlazeTV — the largest multi-platform network of voices who love America, defend the Constitution, and live the American dream.

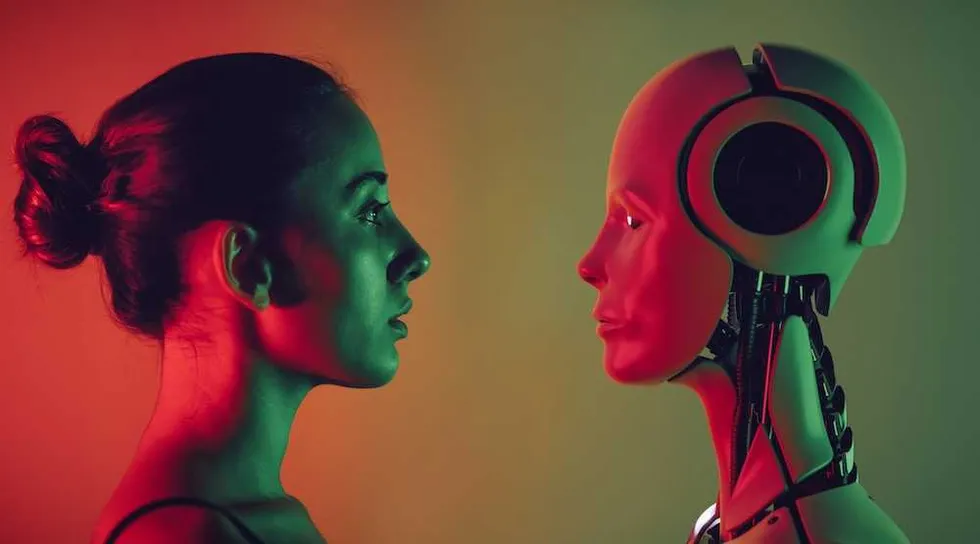

AI can fake a face — but not a soul

The New York Times recently profiled Scott Jacqmein, an actor from Dallas who sold his likeness to TikTok for $750 and a free trip to the Bay Area. He hasn’t landed any TV shows, movies, or commercials, but his AI-generated likeness has — a virtual version of Jacqmein is now “acting” in countless ads on TikTok. As the Times put it, Jacqmein “fields one or two texts a week from acquaintances and friends who are pretty sure they have seen him pitching a peculiar range of businesses on TikTok.”

Now, Jacqmein “has regrets.” But why? He consented to sell his likeness. His image isn’t being used illegally. He wanted to act, and now — at least digitally — he’s acting. His regrets seem less about ethics and more about economics.

The more perfect the imitation, the greater the lie. What people crave isn’t flawless illusion — it’s authenticity.

Times reporter Sapna Maheshwari suggests as much. Her story centers on the lack of royalties and legal protections for people like Jacqmein.

She also raises moral concerns, citing examples where digital avatars were used to promote objectionable products or deliver offensive messages. In one case, Jacqmein’s AI double pitched a “male performance supplement.” In another, a TikTok employee allegedly unleashed AI avatars reciting passages from Hitler’s “Mein Kampf.” TikTok removed the tool that made the videos possible after CNN brought the story to light.

When faces become property

These incidents blur into a larger problem — the same one raised by deepfakes. In recent months, digital impostors have mimicked public figures from Bishop Robert Barron to the pope. The Vatican itself has had to denounce fake homilies generated in the likeness of Leo XIV. Such fabrications can mislead, defame, or humiliate.

But the deepest problem with digital avatars isn’t that they deceive. It’s that they aren’t real.

Even if Jacqmein were paid handsomely and religious figures embraced synthetic preaching as legitimate evangelism, something about the whole enterprise would remain wrong. Selling one’s likeness is a transaction of the soul. It’s unsettling because it treats what’s uniquely human — voice, gesture, and presence — as property to be cloned and sold.

When a person licenses his “digital twin,” he doesn’t just part with data. He commodifies identity itself. The actor’s expressions, tone, and mannerisms become a bundle of intellectual property. Someone else owns them now.

That’s why audiences instinctively recoil at watching AI puppets masquerade and mimic people. Even if the illusion is technically impressive, it feels hollow. A digital replica can’t evoke the same moral or emotional response as a real human being.

Selling the soul

This isn’t a new theme in art or philosophy. In a classic “Simpsons” episode, Bart sells his soul to his pal Milhouse for $5 and soon feels hollow, haunted by nightmares, convinced he’s lost something essential. The joke carries a metaphysical truth: When we surrender what defines us as human — even symbolically — we suffer a real loss.

For those who believe in an immortal soul, as Jesuit philosopher Robert Spitzer argues in “Science at the Doorstep to God,” this loss is more than psychological. To sell one’s likeness is to treat the image of the divine within as a market commodity. The transaction might seem trivial — a harmless digital contract — but the symbolism runs deep.

Oscar Wilde captured this inversion of morality in “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” His protagonist stays eternally young while his portrait, the mirror of his soul, decays. In our digital age, the roles are reversed: The AI avatar remains young and flawless while the human model ages, forgotten and spiritually diminished.

Jacqmein can’t destroy his portrait. It’s contractually owned by someone else. If he wants to stop his digital self from hawking supplements or energy drinks, he’ll need lawyers — and he’ll probably lose. He’s condemned to watch his AI double enjoy a flourishing career while he struggles to pay rent. The scenario reads like a lost episode of “Black Mirror” — a man trapped in a parody of his own success. (In fact, “The Waldo Moment” and “Hang the DJ” come close to this.)

RELATED: Cybernetics promised a merger of human and computer. Then why do we feel so out of the loop?

Photo by imaginima via Getty Images

Photo by imaginima via Getty Images

The moral exit

The conventional answer to this dilemma is regulation: copyright reforms, consent standards, watermarking requirements. But the real solution begins with refusal. Actors shouldn’t sell their avatars. Consumers shouldn’t support platforms that replace people with synthetic ghosts.

If TikTok and other media giants populate their feeds with digital clones, users should boycott them and demand “fair-trade human content.” Just as conscientious shoppers insist on buying ethically sourced goods, viewers should insist on art and advertising made by living, breathing humans.

Tech evangelists argue that AI avatars will soon become indistinguishable from the people they’re modeled on. But that misses the point. The more perfect the imitation, the greater the lie. What people crave isn’t flawless illusion — it’s authenticity. They want to see imperfection, effort, and presence. They want to see life.

If we surrender that, we’ll lose something far more valuable than any acting career or TikTok deal. We’ll lose the very thing that makes us human.

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026