Category: Hollywood

Hallmark of Culture Rot

Comfortingly predictable plots, trite yet charming storylines, guaranteed happy endings, and unrealistically glamorous decorations, wardrobes, homes, villages, and actors made…

Blaze Media • Christmas • Culture • Entertainment • Hollywood • Joy reid

‘Bell’-buster: Joy Reid tries to cancel classic Christmas ‘Jingle’

“Truth. Justice. Whatever.”

Hollywood’s disdain for America is official with the poster tagline for this summer’s “Supergirl.”

‘I don’t care for Owen Wilson, and I don’t care for Matthew Lillard.’

How the industry embraced the problematic “girl” part of the name is a debate for another day. Just know that Hollywood hasn’t been cozy with the classic Superman slogan, “Truth, justice, and the American way,” for some time. The 2006 Brandon Routh reboot infamously ditched that last part, as did this year’s James Gunn version.

Now to show us that this Supergirl can’t even, the phrase is purposely imploded. And to be fair, the results come off better here, if only because the newest Supergirl is a rebel without a cause (or home planet).

Those offended by ditching “the American way” may be more outraged by the accompanying trailer. It looks as gloopy as this past summer’s “Superman” reboot, but with half the gravitas and action.

Prediction: Superhero fatigue goes nuclear in 2026 …

Jay Zzzzzz

Slackers never grow up. They just stay in their parents’ basements indefinitely.

That isn’t true for Jay and Silent Bob. The slacker heroes from Kevin Smith’s imagination refuse to call it a career. They’ve appeared in two features as the key attractions and several Smith movies like the “Clerks” franchise and “Mallrats.”

Now Smith is warning us there’s a third Jay and Silent Bob film in the works. “Jay and Silent Bob: Store Wars” will start production next year. But will anybody show up?

“Jay and Silent Bob Reboot” made under $5 million in 2019. Smith’s last film, “The 4:30 Movie,” didn’t earn enough for BoxOfficeMojo to include its figures.

Smith may have come of age during the ‘90s via “Clerks” and “Chasing Amy,” but his devoted flock has done nothing but shrink since then. Bigly.

Smith, 55, and co-star Jason Mewes, 51, may seem too old to keep cracking pot jokes, but Smith deserves credit for finding enough cash in his sofa to keep his franchise afloat …

Pulp Friction

Quentin Tarantino can’t get criticism out of his system.

The former video store clerk was set to make “The Movie Critic” his 10th and final film, but he got cold feet and went back to the proverbial drawing board. Since then, he’s been criticizing … everything, including specific movie stars.

That’s an unofficial no-no in celebrity circles, but Tarantino is out of you-know-whats apparently.

The director recently slammed actor Paul Dano (“The Batman,” “Love and Mercy”), dubbing the actor “weak sauce” and worse, as part of that now-infamous “Bret Easton Ellis Podcast” interview.

Hollywood stars rallied around Dano, saying he was far better than what the mercurial director dubbed him. Tarantino also shredded two more stars as part of that conversation.

“I don’t care for Owen Wilson, and I don’t care for Matthew Lillard.”

Wilson has yet to publicly respond, but Lillard did just that at a recent Comic-Con-style event, the GalaxyCon in Columbus, Ohio.

“Eh, whatever. Who gives a s**t,” Lillard said before revealing that he actually does give a bleep.

“It hurts your feelings. It f**king sucks,” he said. “And you wouldn’t say that to Tom Cruise. You wouldn’t say that to somebody who’s a top-line actor in Hollywood.”

So far, Lillard’s former co-star Scooby Doo has no comment …

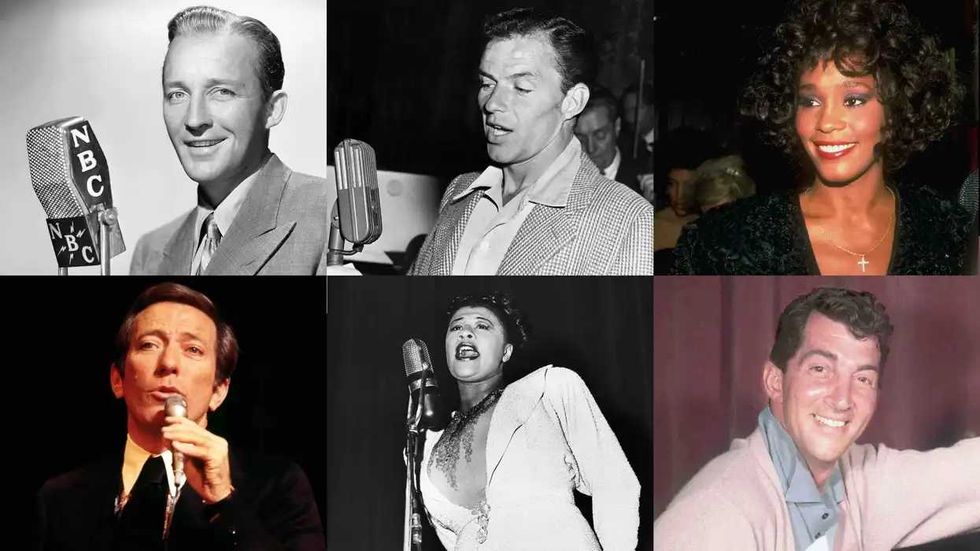

RELATED: These are the definitive recordings of 35 favorite Christmas carols: Don’t argue, just listen

Photo credits, clockwise from top left: NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images; Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images; Robin Platzer/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images; Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images; George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images; David Redfern/Redferns

Photo credits, clockwise from top left: NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images; Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images; Robin Platzer/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images; Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images; George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images; David Redfern/Redferns

‘Jingle’ jerk

The war on “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” is over, and the good guys won. The song continues to play every Christmas season despite a woke attempt to cancel it. The less problematic “remake” by John Legend and Kelly Clarkson was quickly forgotten.

Now former MSNBC host Joy Reid is declaring war on … “Jingle Bells.” And you’ll never guess why. Just kidding.

The song’s writer, James Lord Pierpont, allegedly penned the ditty for racially charged reasons, according to Reid. To her credit, if anyone knows about racially charged topics, it’s a former TV personality who sees racism around every corner.

To her, Elvis Presley’s nickname, “The King,” is racist.

She used a Massachusetts plaque as her “proof” of the song’s racial components, along with Pierpont’s days fighting for the Confederacy. The song’s lyrics appear as benign then as they do now.

Maybe she could record her own version of the song, a la Legend and Clarkson, and watch it follow eight-track tapes, pagers, and MSNBC into the dustbin of history.

Foul, Potty-Mouthed, Woke Women

“I’m not f—ing apologizing for that,” screeched angry actress Amanda Seyfried, who had referred to Charlie Kirk as “hateful” after his…

Can conservatives reclaim pop culture?

Remember when the Duke ruled movie Westerns … studio moguls Walt Disney, Sam Goldwyn and Cecil B. DeMille called the GOP home … and the Hays Code kept movies squeaky-clean?

Well, Hollywood took a left turn about 50 years ago and hasn’t looked back.

Both Mark Wahlberg, a star of deep Christian faith, and actor Zachary Levi are mulling production studios far from the Golden State.

Are we finally ready for a course correction?

Coming attractions

We’ve already seen rebel outfits like the Daily Wire, Breitbart News, and this site’s parent company produce feature films and TV shows from a non-progressive lens. Dude-bro podcasters Joe Rogan and Andrew Schulz ignored the DNC talking points during the 2024 presidential election, with some suggesting their political chats played a role in President Donald Trump’s re-election.

Liberal late-night TV may be going the way of the eight-track tape, given current trends, while the right-leaning “Gutfeld!” outperforms Colbert and company.

That all may be dwarfed by what’s coming next.

David Ellison, son of billionaire Trump supporter Larry, now calls the shots at Paramount after a high-profile deal secured the purchase earlier this year. David Ellison isn’t MAGA, but he’s also not woke or eager to mock half the country.

One of his first deals with Paramount was to secure the rights to UFC events, hardly a coastal elite move. Next June, expect an MMA battle royale on the White House lawn to celebrate the nation’s 250th birthday.

He also purchased the Free Press and named founder Bari Weiss the head of CBS News. Weiss’ company gave conservatives a fair shake and treated the news like … news, not progressive propaganda, under her management.

That suggests Ellison understands the culture wars and thinks appealing to the middle is a wise path forward. It explains why Paramount denounced a far-left celebrity push to boycott Israeli-themed films due to the nation’s so-called genocidal actions against Palestinians.

That’s more MAGA than Hollywood business as usual.

The right stuff

Plus, a November report from Variety shared several Paramount projects with a definitive Heartland appeal, from a “Top Gun” sequel to a “Taken” variation with a cowboy spin. And then there’s the much-publicized “Rush Hour 4” sequel, spurred on reportedly by none other than President Trump himself.

The one early flaw in Ellison’s plans? He allowed TV superstar Taylor Sheridan to flee Paramount for NBCUniversal. Sheridan’s red-state-friendly shows, from “Yellowstone” to “Landman,” have upended the TV landscape, and he’ll only grow stronger under his new deal.

Sheridan’s emergence is another reason for right-leaning optimism. Once again, the prolific creator isn’t conservative, per se, but he’s willing to tell stories today’s Hollywood wouldn’t touch. His male characters exude a rugged, old-school masculinity that is often missing in other parts of the TV landscape.

A Sheridan show sounds and looks different from most modern programs. A perfect case in point? Billy Bob Thornton’s character, a world-weary oil guru, eviscerates the green movement in “Landman” season one. Would a similar rant be heard on any broadcast show? HBO Max? Netflix?

Unlikely.

Zach attack

More intriguing signs abound. Both Mark Wahlberg, a star of deep Christian faith, and actor Zachary Levi are mulling production studios far from the Golden State. That’s more potential disruptions to the status quo, fed by storytellers who don’t pledge allegiance to the progressive flag.

Angel Studios, the successful TV company now making feature films, offers a fresh take on the standard Hollywood slate.

And then there’s the current first lady. Melania Trump is the focus of a new documentary film bowing next month. She’s using her Hollywood close-up to announce a new production company called Muse Films.

That’s following in the Obamas’ footsteps. The former first couple created Higher Ground Productions and partnered up with Netflix after leaving the White House. No matter where one stands on the Obama record, the couple knows cultural soft power matters.

So do the Trumps.

RELATED: Netflix buys Warner Bros. and HBO — here’s what it’ll control

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

Retaking Hollywood

The real X factor may be AI run wild. Conservative artists don’t have the same access to cash that liberals possess. What if a savvy libertarian could create a film via AI, post it on YouTube or Rumble, and rock the culture without breaking the bank? How might that even the culture wars in ways the modern left can’t stop?

Conservatives still have a long, long way to go. Far-left auteur Aaron Sorkin revisits Jan. 6 in the upcoming “The Social Reckoning,” a movie sure to gin up Oscar buzz and endless fawning press coverage following its Oct. 2026 release. It is one of many projects that subscribe to a hard-left perspective.

Take this year’s “One Battle After Another,” a morally warped love letter to anti-government violence. It’s the odds-on favorite to win the Best Picture Oscar come March. Another Oscar darling is “No Other Choice,” director Park Chan-wook’s anti-capitalist screed.

Plus, the Hollywood press will cover most right-leaning entertainment projects in a negative light, hoping to keep pop culture firmly in the hands of progressives. Remember how reporters raged against “Sound of Freedom,” a film cheering efforts to stop child sex traffickers? That movie wasn’t conservative or faith-based, but some assumed it was one or both, and that was enough for media outlets to both pounce and seize on it.

And for every rebel documentary like “The Fall of Minneapolis,” “Am I Racist?” or “October 8,” there are dozens promoting hard-left agendas. The existing Tinseltown infrastructure nurtures and promotes left-leaning stories and storytellers.

That won’t be easy to duplicate, let alone compete against.

Team Ellison will face overwhelming pressure to reject right-leaning impulses from Democrat politicians, media platforms, and garden-variety progressives. It could end up easier for Ellison and company to go along with Hollywood’s liberal orthodoxy than to effect real change.

Or Ellison could see this moment as the perfect time to perform an ideological pivot. The days of ignoring, if not insulting, half the country no longer makes business sense. It’s show business, after all.

And at last that half of the country finally has some storytellers to call its own.

Something to Hold Against Donald Trump

In many ways, Trump is outperforming the expectations many of us had for his second term. Things are going reasonably…

Align • Asian • Blaze Media • Hollywood • Production • Racism

Marvel star’s racist Tinseltown tantrum: ‘Put some asians in literally anything right now’

Actor Simu Liu is begging Hollywood studios for more race-based casting — specifically, his race.

The Chinese-born, Canada-raised Liu recently took to social media to share a collage of screenshots of some of his fellow Asian actors lamenting how hard it is to land leading roles.

“Put some asians in literally anything right now,” Liu added as commentary. “The amount of backslide in our representation onscreen is f**king appalling.”

‘We’re fighting a deeply prejudiced system. And most days it SUCKS.’

White on rice

Citing Hollywood’s apparent fear that Asian-centric films are “risky,” Lui pointed out the success of movies like his 2022 Marvel debut, “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings,” as well as 2018’s “Crazy Rich Asians,” which grossed $174 million in 2018 against a $30 million budget.

“No asian actor has ever lost a studio even close to 100 million dollars,” Liu ranted. “But a white dude will lose 200 million TWICE and roll right into the next tentpole lead. We’re fighting a deeply prejudiced system. And most days it SUCKS.”

RELATED: ‘The Acolyte’ star: Asians need a Tom Cruise of their own

Simu Liu says Asian representation in Hollywood remains “f*cking appalling.”

“Put some Asians in literally anything right now. The amount of backslide in our representation onscreen is f*cking appalling. Studios think we are risky… No Asian actor has ever lost a studio even… pic.twitter.com/EY30BNmhGn

— Variety (@Variety) November 26, 2025

Chinese checkers

Liu’s cries of systemic discrimination did not receive the eager welcome they might have just a few years ago.

On X, investigative journalist Robby Starbuck noted that the film industry in Liu’s native China largely employs Chinese actors.

“Almost none are White. Is that some kind of unfair prejudice too?” he asked. “No, it’s not.”

As Fandom Pulse reported, others mocked Liu’s apparent recycling of “woke talking points from 2018.”

Another reader stated, “Speaking as an asian: representation does not matter. Good stories matter. The right casting for the roles matter. Good acting matters.”

About 99% of actors in films made on mainland China are Asian. Almost none are White. Is that some kind of unfair prejudice too? No, it’s not. It makes sense because most of the market viewing them are Asian too. People need to stop whining. https://t.co/uSZfgm3B1p

— Robby Starbuck (@robbystarbuck) November 28, 2025

Asian persuasion

Back on Threads, however, Liu received a plethora of support from women who agreed that more Asian men should be in lead roles.

“The stories of Asians in the US go deep … the stories deserve to be told,” wrote Karen Johnstone.

While Jayne Nelson added, “I swear it’s slipping back to ‘third henchman from the left in a big fight scene’ and COME ON. It’s not the 1980s anymore.”

One of the actors cited in the original post Liu shared was “The Good Place” star Manny Jacinto, who complained about being cut out of a Tom Cruise movie in 2024.

“It’s up to us — Asian-Americans, people of color — to be that [for ourselves],” Jacinto said at the time. “We can’t wait for somebody else to do it. If we want bigger stories out there, we have to make them for ourselves.”

The other actors cited as making remarks were John Cho (“Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle”), and Daniel Dae Kim (“Lost”).

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Celebrity • Entertainment • Hollywood • Meghan Markle • The American Spectator • The Spectator P.M. Podcast

The Spectator P.M. Ep. 171: Meghan Markle Demands to Be Called by Her Title Everywhere

Anyone expecting Meghan Markle’s presence is formally greeted by someone announcing her as “Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.” A recent interview…

The Incomprehensible Failure of My Attempts to Woo Sydney Sweeney

I’m looking for ways to win Sydney Sweeney over. I thought about sending her flowers, but that’s far too conventional….

Blaze Media • Culture • Entertainment • Hollywood • Lucy liu • Wicked

Sore Liu-ser: Multimillionaire ‘Kill Bill’ star gripes about ‘Caucasian’-heavy Hollywood

Boo-hoo, Lucy Liu.

The veteran actress is in the awards season mix for “Rosemead,” the tale of an immigrant grappling with a troubled teenage son. That means she’s working the press circuit, talking to as many media outlets as she can to promote a possible Best Actress nomination.

No more peeks at Erivo’s extended, Freddy Krueger-like nails or Grande waving away a helicopter overhead as if it were about to swoop down on them.

If you think political campaigns are cynical, you haven’t seen an actor push for a golden statuette. That may explain why Liu shared her victimhood story with the Hollywood Reporter.

Turns out the chronically employed star (123 acting credits, according to IMDB.com) hasn’t been employed enough, by her standards.

I remember being like, “Why isn’t there more happening?” … I didn’t want to participate in anything where I felt like they weren’t even taking me seriously. How am I being given these offers that are less than when I started in this business? It was a sign of disrespect to me, and I didn’t really want that. I didn’t want to acquiesce to that … I cannot turn myself into somebody who looks Caucasian, but if I could, I would’ve had so many more opportunities.

Liu has had the kind of career most actors would kill to duplicate. That doesn’t play on the identity politics guilt of her peers though. Nor is it fodder for a “woe is me” awards speech …

Rest for the ‘Wicked’

That’s a wrap!

The “Wicked: For Good” press push got the heave-ho earlier this week when star Cynthia Erivo reportedly lost her voice. Co-star Ariana Grande pulled out of her appearances in solidarity.

Yup. Not remotely suspicious.

The duo made way too many headlines last year during their initial “Wicked” press tour. Why? It was just … weird. Odd. Creepy. The stars’ emaciated appearance didn’t help, but their kooky, collective affect was off-putting, to be kind.

Even the Free Press called out the duo’s sadly emaciated state.

They trotted out more of the same for round two, and someone had the good sense to yank them off the stage before the bulletproof sequel hit theaters Nov. 21.

No more peeks at Erivo’s extended, Freddy Krueger-like nails or Grande waving away a helicopter overhead as if it were about to swoop down on them.

Any publicity is good publicity, right? Not when it’s wickedly cringe …

RELATED: ‘Last Days’ brings empathy to doomed Sentinel Island missionary’s story

Vertical

Vertical

Face for radio

John Oliver thinks it’s 1985.

HBO’s far-left lip flapper is furious that the Trump administration stripped NPR of its federal funding. Who will ignore senile presidents and laptop scandals without our hard-earned dollars?

Think of the children!

Never mind that Americans have endless ways to access news, from AM radio to TV, satellite, cable, and streaming options. Heck, just pick up a $20 set of rabbit ears, and you’ll get a crush of local TV stations in many swathes of the country.

You have to live in a bunker a hundred feet below the earth to avoid the news.

Oliver, to his credit, put his money where his mouth is. Or at least, your money. He set up a public auction to raise cash for NPR stations.

Why? Because we’re all going to croak without it. That’s assuming you didn’t die following the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the lack of net neutrality.

“Public radio saves lives. The emergency broadcast system. Without it, people would die.”

A second-rate satirist might have a field day with anyone pushing the “you’ll die without X, Y, or Z” card. Alas Oliver doesn’t warrant that ranking …

‘Running’ on empty

Rising star status ain’t what it used to be.

Glen Powell seemed like the next Tom Cruise for a hot minute. Handsome. Affable. Unwilling to insult half the country. He stole a few moments during “Top Gun: Maverick” and powered a mediocre rom-com — 2023’s “Anyone but You” — into a $220 million global hit.

So when Hollywood handed him the keys to the “Running Man” remake, the industry assumed he had finally arrived. Give him his “I’m on the A-List” smoking jacket.

That’s until the remake’s opening weekend numbers came in. Or rather trickled in. That $16 million-plus haul just won’t cut it.

Now Powell’s next film is under the microscope. The project dubbed “Huntington” just got a last-minute name change to “How to Make a Killing.” The film follows Powell’s character as he tries to ensure he’ll inherit millions from his uber-wealthy family. That’s despite getting cast out of the clan’s good graces.

The movie now has a Feb. 20 release date, hardly a key window for an A-lister like Powell.

Then again, his time on the A-list may have already expired.

The Spectacle Ep. 300: Why Movies Suck: Screenwriter Lou Aguilar Tells the Story

As the struggling film industry faces an all-time low in ratings and box office performance, can conservatives step up to…

search

calander

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026