Category: School

Blaze Media • Faith • God • Mcconaughey • School • Texas

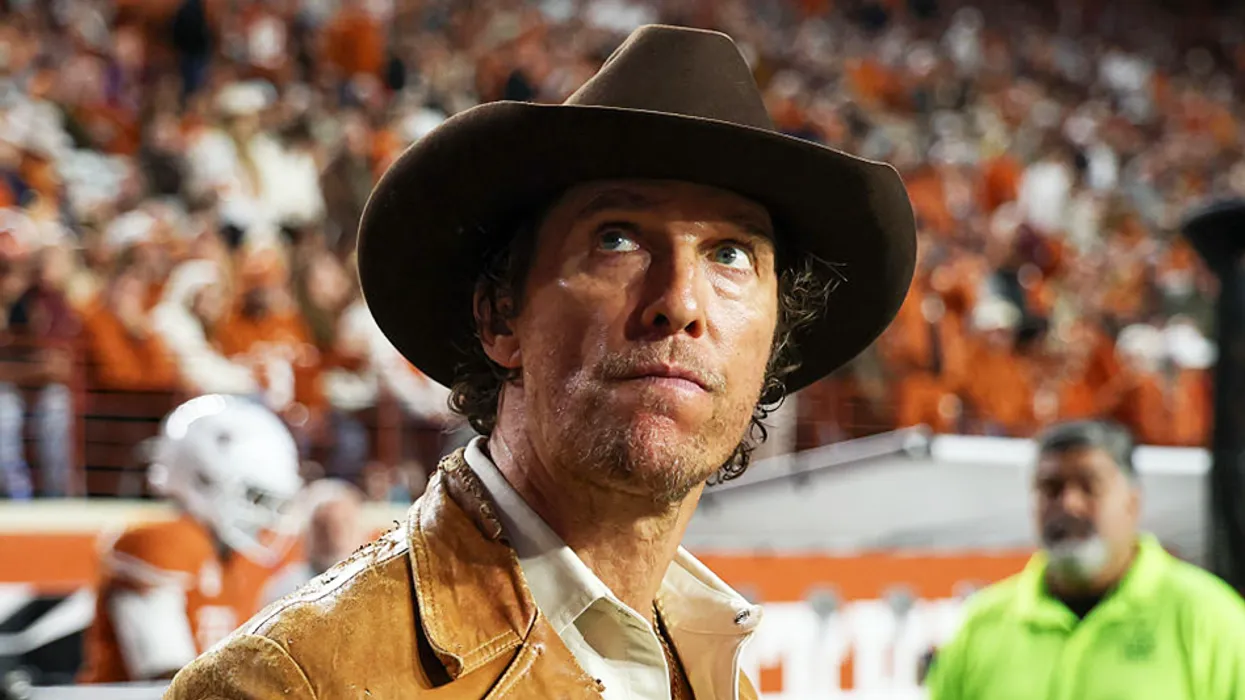

Matthew McConaughey: Choose God and family, not ‘participation trophies’

Matthew McConaughey doesn’t want participation trophies, and he doesn’t want success to be watered down.

The iconic actor recently gave a speech only he could deliver, forgoing giving traditional advice in favor of providing his own spiritual leanings that work for him.

‘I think in the West, because we want everyone to feel really great, participation trophies!’

The movie star was asked about how he critiques his performances on screen and how he gauges success.

“I know if I’m bogeying or if I’m birdieing. … I’ve seen myself on screen [and thought], ‘You’re kind of bulls***ting there,'” McConaughey told host Jay Shetty on his podcast.

Faking the grade

From there, McConaughey trashed the idea of expanded grade-point averages through extra credit.

“I’m not into extra credit. I don’t like 4.2 GPAs. That tells me, like, what happened? Are we, then, we’re not giving the right test? If 4.0 was the pinnacle, you know, that means not many people should be getting it, if anybody,” he explained.

The Texan said that with higher scores, institutions have either over-leveraged the original task or broadened the scope of scoring and therefore cheapened the credit.

“I think in the West, because we want everyone to feel really great, participation trophies! 4.2 GPA. Well, I feel better,” he said sarcastically.

It was from there that McConaughey began to explain where he seeks validation from, which was the true shining light of the discussion.

RELATED: Matthew McConaughey calls for ‘gun responsibility’ not gun control, goes on to demand gun control

Heavenly helpers

Aside from his wife and kids, McConaughey revealed he has a trio of people in heaven that he looks to for reactions — and God’s reaction through them.

“I have a council in the sky. Three people that are extremely important to me in my life: my dad, Penny Allen, and John Cheney.”

While the 56-year-old explained that Cheney is his old friend, it was not clear who Allen is.

“I see them, wink at them, talk with them, listen to them … run ideas by them, run decisions by them, and then I look up and see what their reaction is. And it’s been a very trusted council for me.”

This is a way to put “souls that are no longer with us” in “a heaven sense,” he explained. “They’re a conduit from God to me, and I have no expectations of them.”

In God he trusts

It doesn’t always go well for McConaughey, though. Sometimes his dad is “dancing in his underwear with a Miller Lite and a piece of lemon meringue pie,” he laughed, but sometimes “they’re not dancing,” and he has to figure out why.

RELATED: Matt Damon: Netflix dumbs down movies for attention-impaired phone addicts

Photo by PG/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images

Photo by PG/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images

The Uvalde, Texas, native said it is very important to him to not have a picture of God in his mind, as he does not want to minimize his meaning.

In the end though, this all leads to McConaughey seeking his own validation, he admitted.

“I try to measure how I counsel and referee myself off of some of the people I just brought up to you,” he told the host.

“That’s where I prove it.”

McConaughey added that he does not look too far outside his own circle, because those he knows are who he trusts.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Assessment • Blaze Media • Education • Mississippi • Naep • School

Mississippi ‘miracle’ catapults 4th-grade reading scores from bottom into top 10 by getting back to phonics

In 2013, Mississippi ranked 49th out of the 50 U.S. states in grade four reading achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — the largest continuing national assessment of American students’ knowledge and capability in math, reading, science, and writing.

In what has repeatedly been dubbed a “miracle,” the state made its way up the list — to 29th in 2019 and then 10 spots higher to ninth place nationally for reading scores last year.

According to the NAEP, black students in Mississippi ranked third nationally last year among their cohort for reading and math scores; Hispanic students in the state ranked first in the nation for reading and second for math scores; and poor students in the Magnolia State ranked first for reading and second for math scores nationally.

‘No, it’s not impossible to teach children, and no, it’s not very costly.’

The assessment noted that “Mississippi is one of only a few states with improved NAEP scores since 2013. In most states, NAEP scores have been falling over the past decade.”

While there have been numerous attempts to explain Mississippi’s success, it appears the “Mississippi miracle” is attributable ultimately to the state’s 2013 Literacy-Based Promotion Act, which conservative commentator Rich Lowry recently noted effectively came down to adopting phonics and setting high standards for students.

Noah Spencer, a researcher at the University of Toronto’s economics department, analyzed the impact of the LBPA — the three pillars of which are improving teaching, identifying and helping kids with reading deficiencies, and holding back third-graders who can’t hack it on an end-of-year reading assessment — in a study published last year in the Economics of Education Review. Spencer found that:

the policy, which included investments in teacher training and coaching, early screening for and targeted assistance to struggling readers, and retention for deficient readers, increased both grade 4 reading and math test scores on a national assessment by 0.14 and 0.18 [standard deviations], respectively, for students with any amount of exposure to the policy, and by 0.23 and 0.29 SDs for students with K-3 exposure to the policy.

Spencer stressed the significance of these increases, citing previous research that found “that ‘children with test scores that are one standard deviation higher at age 12 report 1-2 more years of schooling by age 22’ in the lower- and middle-income countries they study.”

RELATED: Trump admin takes major step toward dismantling Department of Education

Linda McMahon. Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images

Linda McMahon. Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images

“While these estimates likely do not apply precisely to Mississippi’s context, it does seem reasonable to suggest that, given the LBPA’s sizable effects on test scores for children exposed from kindergarten to grade 3, it may also increase earnings for exposed cohorts in the future,” wrote Spencer. “The impressive effects of this policy change should be noted by policymakers in other jurisdictions.”

Lowry echoed this sentiment, noting that Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee, which have employed similar strategies, have also made gains.

“With reading scores nationally sliding the wrong way, especially for the bottom 10% of students, Mississippi and the other Southern states offer a beacon of hope,” wrote Lowry. “Their example shows that, no, it’s not impossible to teach children, and no, it’s not very costly. It’s a good sign that even California just passed a phonics bill.”

‘It’s really smart, local innovation at work.’

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon has extolled the approach taken in Mississippi, telling the New York Post in September, “What I’m seeing now is a great return to classical learning.”

“We’ve tried a lot of things, you know — No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top — and I believe they were done with the best of intentions, but they were not successful,” said McMahon. “But what we have clearly seen is the science of reading is successful.”

Despite the noted success of the LBPA in Mississippi, some lawmakers around the country still haven’t taken the hint.

Democrats in Michigan, for instance, reportedly repealed similar reforms, eliminating, for instance, an A-F grade-ranking system for every public school in the state and scrapping the requirement that illiterate third-graders get held back.

Whereas last year, the average score of fourth-grade students in Mississippi for reading was 219/500 — higher than the national average score of 214 — the average score in Michigan was 209, which was lower than scores in 31 other states and jurisdictions.

The Mississippi Department of Education announced on Nov. 13 that 85% of the Magnolia State’s third-graders passed the reading assignment required to transition to grade four, a 1-percentage-point increase over last year.

The U.S. Department of Education noted, “Mississippi’s literacy climb may be called ‘miracle,’ but it’s really smart, local innovation at work.”

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Reversing Clinton Judge Appeals Court Rules Students Can’t be Punished for using Transgender Classmates’ Biological Pronouns

Is the learning environment disrupted when students in kindergarten through high school refer to all classmates—including those who identify as transgender—by their biological pronoun? A public school district in Ohio claims it is and a few years ago enacted an “anti-harassment” policy that punishes students who refuse to use the preferred pronouns of transgender classmates. […]

The post Reversing Clinton Judge Appeals Court Rules Students Can’t be Punished for using Transgender Classmates’ Biological Pronouns appeared first on Judicial Watch.

Academia • Academics • Blaze Media • College • School • University

Coddled Harvard students cry after dean exposes grade inflation, ‘relaxed’ standards

Harvard University’s Office of Undergraduate Education released a 25-page report on Monday revealing that roughly 60% of the grades dished out in undergraduate classes are As. This is apparently not a signal that the students are necessarily better or smarter than past cohorts but rather that Harvard As are now easier to come by.

According to the report, authored by the school’s dean of undergraduate education Amanda Claybaugh and reviewed by the Harvard Crimson, the proportion of students receiving A grades since 2015 has risen by 20 percentage points.

‘If that standard is raised even more, it’s unrealistic to assume that people will enjoy their classes.’

Whereas at the time of graduation, the median grade point average for the class of 2015 was 3.64, it was 3.83 for the class of 2025 — and the Harvard GPA has been an A since the 2016-2017 academic year.

“Nearly all faculty expressed serious concern,” wrote Claybaugh. “They perceive there to be a misalignment between the grades awarded and the quality of student work.”

Citing responses from faculty and students, the report revealed that the specific functions of grading — motivating students, indicating mastery of subject matter, and separating the wheat from the chaff — are not being fulfilled.

RELATED: Harvard posts deficit of over $110 million as funding feud with Trump continues to sting

Photo by Zhu Ziyu/VCG via Getty Images

Photo by Zhu Ziyu/VCG via Getty Images

“In the view of faculty, grades currently distinguish between work that meets expectations or fails to meet expectations, but beyond that grades don’t distinguish much at all,” said the report. “‘Students know that an ‘A’ can be awarded,’ one faculty member observed, ‘for anything from outstanding work to reasonably satisfactory work. It’s a farce.'”

Claybaugh acknowledged that grades can serve as a useful and transparent way to “distinguish the strongest student work for the purposes of honors, prizes, and applications to professional and graduate schools.” However, since As are now handed out like candy and many students have identical GPAs, prizes and other benefits must now be dispensed on the basis of less objective factors, which “risks introducing bias and inconsistency into the process,” suggested the dean.

The report noted further that Harvard University’s current grading practices “are not only undermining the functions of grading; they are also damaging the academic culture of the College more generally” by constraining student choice, exacerbating stress, and “hollowing out academics.”

Steven McGuire, a fellow at the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, highlighted the admission in the report that Harvard owes much of its current crisis to its coddling of unprepared students.

“For the past decade or so, the College has been exhorting faculty to remember that some students arrive less prepared for college than others, that some are struggling with difficult family situations or other challenges, that many are struggling with imposter syndrome — and nearly all are suffering from stress,” said the report.

“Unsure how best to support their students, many have simply become more lenient. Requirements were relaxed, and grades were raised, particularly in the year of remote instruction,” continued the report. “This leniency, while well-intentioned, has had pernicious effects.”

The new report is hardly the first time the school has suggested that Harvard undergraduate students tend to be coddled, intellectually fragile, ideologically rigid, and slothful.

Citing faculty feedback, Harvard’s Classroom Social Compact Committee indicated in a January report that undergraduate students “have rising expectations for high grades, but falling expectations for effort”; often don’t attend class; frequently don’t do many of the assigned readings; seek out easy courses; and in some cases are “uncomfortable with curricular content that is not aligned with the student’s moral framework.”

The January report noted further that “some teaching fellows grade too easily because they fear negative student feedback.”

Claybaugh’s grade inflation report has reportedly prompted complaints and whining this week from students.

Among the dozens of students who objected to the report and its findings was Sophie Chumburidze, who told the Harvard Crimson, “The whole entire day, I was crying.”

“I skipped classes on Monday, and I was just sobbing in bed because I felt like I try so hard in my classes, and my grades aren’t even the best,” said Chumburidze. “It just felt soul-crushing.”

Kayta Aronson told the Crimson that higher standards could adversely impact students’ health.

“It makes me rethink my decision to come to the school,” said Aronson. “I killed myself all throughout high school to try and get into this school. I was looking forward to being fulfilled by my studies now, rather than being killed by them.”

Zahra Rohaninejad suggested that raising standards might sap the enjoyment out of the Harvard experience.

“I can’t reach my maximum level of enjoyment just learning the material because I’m so anxious about the midterm, so anxious about the papers, and because I know it’s so harshly graded,” said Rohaninejad. “If that standard is raised even more, it’s unrealistic to assume that people will enjoy their classes.”

The student paper indicated the university did not respond to its request for comment.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026