Category: Syria

Wake up and smell the Islamic invasion of the West

Over the course of a single day this month, a pattern repeated itself across the West. Two Muslims murdered at least 15 people at a Hanukkah celebration in Sydney. Five Muslims were arrested for plotting an attack on a Christmas market in Germany. French authorities canceled a concert in Paris due to credible threats of an Islamist terror attack. Two Iowa National Guardsmen in Syria were murdered by an Islamist while we play footsie with an illegitimate regime.

None of this represents an anomaly. It represents the accumulated failure of a strategy best summarized as “invade the Muslim world, invite the Muslim world.”

This conflict has never been about Jews alone. Jews are the first target, not the last. Islamist ideology ultimately targets all non-Muslims and any society that refuses submission.

That doctrine has produced neither peace abroad nor safety at home.

A contradiction the West refuses to resolve

Western governments spent the better part of a generation importing millions of migrants from unstable regions while simultaneously deploying their own soldiers to those same regions to manage sectarian civil wars.

The contradiction remains unresolved: We accept the risks of mass migration while risking our troops to contain the same ideologies overseas.

Islamist movements do not confine themselves to national borders. Whether Sunni or Shia, whether operating in Syria, Europe, or North America, the targets remain consistent: Jews, Christians, secular institutions, and Western civil society.

Yet our policy treats these threats as isolated incidents rather than the expression of a coherent ideology.

Strategic incoherence in Syria

Nowhere does this incoherence appear more starkly than in Syria.

On one hand, the Trump administration has moved toward normalizing relations with Syria’s new leadership. In June, President Trump signed an executive order terminating U.S. sanctions on Syria, including those on its central bank, in the name of reconstruction and investment. Last month, Syria’s new leader, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani — a former al-Qaeda figure rebranded as a statesman — visited the White House, where Trump publicly praised developments under the new regime and said he was “very satisfied” with Syria’s direction.

At the same time, Trump floated the idea of establishing a permanent U.S. military base in Damascus to solidify America’s indefensible presence and support the new government.

This would be extraordinary. The United States would be embedding troops deeper into one of the most volatile theaters on earth, effectively placing American soldiers at the mercy of a regime whose leadership and allies only recently emerged from jihadist networks — including factions accused of massacring Christians and Druze.

Simultaneously, the White House pressures Israel to limit its defensive operations in southern Syria, including its buffer-zone strategy along the Golan Heights, even as Israeli forces do a far more effective job degrading jihadist threats without sacrificing their own soldiers.

The result is perverse: America risks lives to stabilize an Islamist-adjacent regime while restraining the one ally actually capable of enforcing order.

Wars abroad, chaos at home

The contradiction deepens when immigration policy enters the picture.

Despite Syria remaining one of the world’s most unstable countries, with no reliable vetting infrastructure, the United States continues admitting Syrian migrants while maintaining roughly 800 troops inside Syria with no clear mission, no defined end, and no defensible supply lines.

Worse, U.S. forces increasingly find themselves aligned with terrorist factions tied to al-Jolani’s coalition to manage rival Islamist groups — placing American soldiers in the same position they occupied in Afghanistan, where “allies” repeatedly turned on them.

That dynamic produced deadly ambushes then. It is happening again.

Qatar’s fingerprints all over

The common thread running through Syria, Gaza, immigration policy, and Islamist indulgence is Qatar.

Qatar (along with our NATO “ally,” Turkey) invested heavily in Sunni Islamist factions during Syria’s civil war and backed networks tied to the Muslim Brotherhood for more than a decade. Qatar hosts Islamist leaders, bankrolls ideological infrastructure, and operates Al Jazeera, a media outlet that consistently amplifies anti-Western and anti-Israel narratives.

Yet Qatari preferences increasingly shape Western policy. We remain in Syria. We soften pressure on Islamist factions. We tolerate Muslim Brotherhood networks operating domestically. We allow Al Jazeera to function with broad access and influence inside the United States.

These choices do not occur in isolation. They align consistently with Qatari interests.

Unfettered immigration kills

Which brings us to the attack in Sydney that killed at least 15 people and wounded dozens more, when two Muslim terrorists opened fire on a Hanukkah celebration — using weapons supposedly banned in a country that prides itself on gun control, but not border control.

The alleged attackers, Sajid Akram and Naveed Akram, were a father-and-son pair of Pakistani origin. Sajid Akram entered Australia from Pakistan in 1998 on a student visa, converted it to a partner visa in 2001, and later received permanent residency through resident return visas.

In other words, this was not a transient or marginal figure. Akram was educated, had lived in Australia for more than 25 years, raised an Australian-born son, and still became radicalized enough to murder Jews in his adopted country.

Pakistan is one of the countries the Trump administration continues to treat as an ally, allowing large numbers of its nationals into the United States. Over the past decade, roughly 140,000 Pakistanis have received green cards, with tens of thousands more entering on student and work visas.

RELATED: Political Islam is playing the long game — America isn’t even playing

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

The same pattern appears elsewhere. In Germany, five terrorists arrested for plotting an attack on a Christmas market came from Morocco, Syria, and Egypt. In the U.S., we have issued green cards to approximately 38,000 Moroccans, more than 100,000 Egyptians, and over 28,000 Syrians.

This problem is not confined to ISIS or a handful of extremists in distant war zones. It is systemic. It explains why thousands took to the streets celebrating the Sydney massacre and why Islamist mobs now routinely surround synagogues in American cities, blocking worshippers and daring authorities to intervene.

The truth is, it doesn’t matter which Islamic country they hail from, how friendly that government may be to the West, or the tribal dynamics on the ground there. All of them, when they cluster in large numbers and form independent communities run by the Musim Brotherhood organizations, are incompatible with the West.

The problem is with Islam itself and the mass migration and Western subversion promoted by the Muslim Brotherhood through Qatari and Turkish gaslighting.

A choice we keep postponing

This conflict has never been about Jews alone. Jews are the first target, not the last. Islamist ideology ultimately targets all non-Muslims and any society that refuses submission.

The West must decide whether it intends to defend its civilization or continue subsidizing its erosion — through mass migration without assimilation, foreign entanglements without strategy, and alliances that demand silence in exchange for access.

Rather than building up Syria, risking the lives of our troops, and continuing to appease our enemies in Qatar, why not pull out, let Israel serve as the regional security force, while we focus on closing our border to the religion of pieces?

Protecting the country requires clarity. That means ending immigration from jihadist incubators, dismantling Islamist networks operating domestically, withdrawing troops from unwinnable sectarian conflicts, and empowering allies who actually fight our enemies.

Anything less is not “compassion” or sound foreign policy. It is criminal negligence.

This Christmas season, Middle East Christians are under threat

Last December, my country finally threw off the chains of a hated, despotic regime. For many Syrians, it was a moment filled with hope — the belief that decades of repression had given way to a chance for renewal. Yet by March 2025, that hope had begun to fade. Parts of the country slipped into chaos. Videos circulated on social media and WhatsApp showing armed Islamist militias attacking civilian Christians, Druze, and anyone they branded as “infidels.”

Homes were burned. Entire families were killed. The first wave of violence was expanding and closing in on Christian communities of Suwayda in southern Syria, where many of my family members live.

While Israel has faced a campaign of withering international criticism, American Catholics and evangelicals are hearing very little about the plight of Christians from Egypt to Iran.

Then the killing stopped. It wasn’t widely publicized, but Israel — Syria’s southern neighbor — stepped in to prevent a massacre. Decisive military action stopped the slaughter of men, women, and children — our own relatives — in Suwayda.

For Arab Christians who have lived through so much war and persecution, it was a moment of relief but also a reminder of how little the world seems to care. When Christians are murdered in the Middle East, it rarely makes headlines.

As we come into the Christmas season and a new year, Christians are vanishing under Islamist violence and official repression.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah’s control and Iranian power have sent the Christian population into a tailspin. In Iraq, the number of Christians has dwindled to just over 100,000 faithful from over one million barely a decade ago. Even in small pockets of Christian life, supposed “safe havens” like Ain Kawa in Erbil, Iraq, Christians survive only because local authorities offer protection. From Sudan to Syria, ancient Christian communities have collapsed in just a generation.

The cradle of Christianity, with few exceptions, has become a region where believers cannot worship or gather without threats to our lives. Intervention from Israel helped prevent a massacre of Christian communities in Suwayda. But the world needs to pay attention to protect the Christians of the Arab world.

Western interest in the Middle East has mostly focused on Hamas’ brutal attacks on Israel in 2023 and Israel’s counteroffensive in Gaza. While Israel has faced a campaign of withering international criticism, American Catholics and evangelicals are hearing very little about the plight of Christians from Egypt to Iran. Legacy media ignores them. TikTok algorithms suppress them.

It is perverse that right now — with Christian communities across the Middle East facing extinction — prominent voices like Tucker Carlson and Nick Fuentes are ostracizing Christian Zionism as “a heresy.” In fact, Israel is the best friend Christians in the Middle East can hope to have. Alone in the region, Israel hosts a growing Christian population; alone in the region, Israel has intervened time and again to save Christian communities from eradication.

RELATED: The real question isn’t war or peace — it’s which century we choose

Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images

Our brethren in Syria and across the Middle East need our help this year more than ever before. Where churches are destroyed and believers persecuted, American Christians must pay attention, pray, and speak out.

More than that — contra Carlson — let us reach beyond our community. We can and must bring together a coalition of conscience in defense of persecuted minorities abroad, including human rights NGOs, brave anti-Islamist Muslims, and friendly governments in the region.

As Christmas approaches, the Christians of the Arab world are desperately calling for our help. This season, let us answer them.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.

The pernicious myth that America doesn’t win wars

False narratives have a way of being taken as fact in popular understanding. After years of repetition, these statements calcify into articles of faith, not only going unchallenged, but having any counterarguments met with incredulity, as though the person making the alternative case must be uninformed or unaware of the established consensus. Many people simply accept these narratives and form worldviews based on them, denying the reality that, if the underlying assumption is wrong, then so are the decisions that flow from it.

One narrative that has taken hold among many since the humiliating end to the war in Afghanistan is that the U.S. military doesn’t win wars, or that it hasn’t since the end of World War II. This critique of the armed forces, foreign policy, or use of force has become an ironclad truth among many who use it as a starting point to advocate their own preferred change.

The United States military has had plenty of successes since World War II and, in fact, has suffered only a small handful of definitive losses in that time.

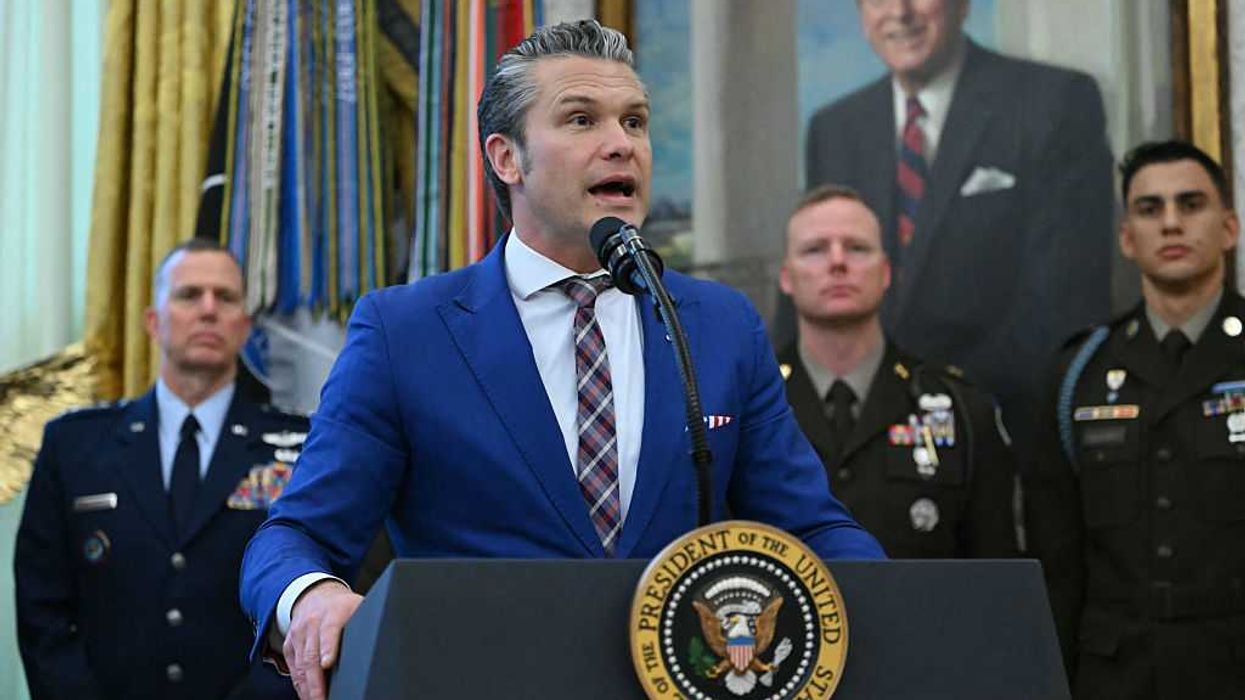

Advocates of War Secretary Pete Hegseth’s vision for the military have echoed it: “The military had grown weak and woke, so we need to change the culture, ignore or at least diminish adherence to legal restraints, and remake the composition of the military.” Restrainers, isolationists, and America Firsters have joined the chorus: “America has given up blood and treasure on stupid wars in which we were failures.”

There is only one problem with this understanding, and more importantly, its use as a baseline from which to derive policy prescriptions — it isn’t true at all.

Ignorance of war

It reflects a misunderstanding of how America has used force and what we have and haven’t achieved. And unlike many misunderstandings about American defense, this one isn’t solely by those with little familiarity with what the military does; the view has taken hold among many who should know better. There are several reasons for belief in the fallacy.

First, there is ignorance of what a war is, or at least not having a common definition of it.

For the pedants, one could point out that the United States has not been at war, by strict definition, since 1945. However, this isn’t relevant to the topic at hand because if the United States has not fought a war since 1945, then by this definition, we also haven’t lost one. In fact, the United States has declared war many times: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, and the World Wars, yet we have engaged in armed conflict significantly more often than that.

So for the purposes of this debate, we can reflect upon the United States using force to achieve foreign policy objectives. With this more expansive definition, then Grenada is just as much of a war as World War II (although the latter certainly is a source of more pride than the former).

Second, there is ignorance of the number of conflicts in which the United States has been involved. Americans tend to have short memories and often pay less attention to events beyond the water’s edge. Many are largely ignorant of ongoing, smaller operations being conducted in their name. (Remember the shocked response to the Niger incident when many people, including congressional leaders, announced their ignorance of U.S. presence there?)

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the passage of time. How many Americans are aware of our involvement in the Dominican Civil War in 1965? Or the various conflicts that made up the Banana Wars?

RELATED: Turns out that Hegseth’s ‘kill them all’ line was another media invention

Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP via Getty Images

Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP via Getty Images

Third, there is ignorance or misunderstanding of the outcome of those wars. Our perspective has been skewed, likely due to the recent history of the embarrassing and self-inflicted defeat in Afghanistan, the messy and confusing nature of the war in Iraq, and the historic examples of very clearly defined wars with obviously complete victories.

There was no ambiguity in the World Wars. The United States went to war with an adversary nation state (or coalition of them), fought their uniformed militaries, and ended these with a formal surrender ceremony abroad and victory parades at home. But this is not the norm, neither for American military intervention nor for conflict in general.

Most of American military history does not look like these examples — conflicts that are large in scale, discrete in time, and definitive in outcome. Some of our previous interventions have been short in duration and were clear victories but smaller in scale (e.g., Grenada and Panama). Some have been clear victories but incremental, fought sporadically with fits and starts and over the course of years, if not decades (e.g., the several smaller conflicts that are often lumped together under the umbrella of the Indian Wars).

Win, lose, draw

But then there is another category — one in which the conflict results in a seemingly less satisfying but mostly successful result, sometimes after a series of stupid and costly errors and sometimes after years of grinding conflict that ends gradually rather than with a dramatic ceremony.

The Korean War, often described as a “draw” because the border between North and South Korea remains today where it was before the beginning of the war, had moments of highs and lows, periods where it seemed nothing could prevent a U.S.-led total victory — only to see the multinational force squander its advantage (e.g., reaching the Yalu River) and moments where all seemed lost, only to escape from the jaws of defeat through audacity and courage (e.g., Chosin Reservoir, Pusan, Inchon).

When President Truman committed U.S. forces as part of the U.N. mission to respond to communist aggression, the stated intent was to assist the Republic of Korea in repelling the invasion and to maintain its independence. South Korea still exists to this day. The combined communist forces of the PRK and CCP were prevented from achieving their aims by American military power.

We have a much more recent (and undoubtedly more controversial) example of a misunderstood success. Many of those who ballyhoo about America not winning wars point not only to the failure in Afghanistan but also to the recent war in Iraq. The Iraq War was many things — initially fought with great tactical and operational brilliance, then sinking into lethargic and incompetent counterinsurgency, then adapting to local power structures, and of course, initiated under pretenses we now know to be incorrect. But it was not, despite the ironclad popular perception, a military failure.

The military set out, with the invasion of 2003, to defeat the combined forces of the Iraqi Army and Republican Guard and remove the Ba’athist government from power. We achieved that goal. Once in control of Baghdad, the U.S. faced a new threat — one of a growing and complex insurgency that we had failed to anticipate. American forces under Ricardo Sanchez, and continuing under George Casey, seemed perplexed and frustrated by a conflict they had not come prepared to fight, nor that they adapted to. For years, despite the insistence of many military and political leaders, the war was not going our way as American casualties increased month after month.

But by 2008, the Sahwa — the movement of Sunni tribal militias aligning with the U.S.-led coalition and the government in Baghdad — and the American efforts to adapt to a more effective counterinsurgency strategy were turning the tide, to the point that by 2010, the violence in Iraq had largely subsided.

The government the United States helped bring about in Baghdad to replace Saddam Hussein endures to this day but not without difficulties. In his 2005 “National Strategy for Victory in Iraq,” George W. Bush defined victory in the long term as an Iraq that is “peaceful, united, stable, and secure, well-integrated into the international community, and a full partner in the global war on terrorism.” By continuing to maintain a relationship with Iraq, we are helping shape this long-term result, just as we did as we helped postwar Germany and Korea maintain security and political stability.

Due to the oppressive steps of a flawed prime minister, American desire to recede from presence and oversight in Iraq, and a compounding effect of spillover from the Syrian Civil War, there was the need for further American assistance in defeating the threat from ISIS, but defeat them we did — another success for the American military.

The Iraqi government also has close relationships with our Iranian regional rivals, as many of the local Arab countries do based on proximity. But just as the need for the 2nd and 3rd Punic Wars does not change the fact the 1st Punic War was a Roman victory, the war against ISIS does not change the fact that the United States accomplished the goal of deposing and replacing Saddam Hussein. Likewise the fact that the Soviet Union gained influence over Eastern Europe does not change the fact that World War II ended in a definitive defeat of the Nazis.

What does victory look like?

None of that changes a separate question, however — whether the war was worth it. But that was a political decision and one that does not negate the truth that the U.S. military first defeated the Iraqi military in a decisive win and then quelled a grinding insurgency in a less decisive way.

Just because a victory isn’t total doesn’t mean that the military fighting it lost. The War of 1812 was a victory, despite the fact the U.S. failed to achieve its maximalist goals of incorporating Canada but did achieve the goal for which the war was fought — rejecting British attempts to deny American sovereignty. World War II was a victory, despite the fact it set conditions for the Cold War and communist oppression. Korea was a victory, despite the fact we did not unify the Koreas under the democratic South. And Iraq was a victory — a poorly decided, stupidly managed, and possibly counterproductive long-term victory.

RELATED: Trump forced allies to pay up — and it worked

Photo by Pier Marco Tacca/Getty Images

Photo by Pier Marco Tacca/Getty Images

When viewed in this way, the United States military has had plenty of successes since World War II and, in fact, has suffered only a small handful of definitive losses in that time — Vietnam, Iran (Operation Eagle Claw), Somalia (1993), and Afghanistan — with the temporal proximity of the latter and the fact that two of these were also America’s longest conflicts, helping to warp the public’s understanding of our military effectiveness.

None of this is to say that America should not take a harsh look at our recent military efforts and seek continuous improvement. Grenada, as I have mentioned, was a victory but an incredibly embarrassing one that was likely only successful because we fought a backwater Caribbean country with a population of less than 100,000. The hard lessons learned by examining the disasters, mistakes, and close calls from Operation Urgent Fury helped reform the military into the globally dominant force that defeated the world’s fourth largest army in 100 hours less than a decade later.

Americans should not look at our military through rose-colored glasses, chest thumping as we chant “USA” and insisting that no other force can land a glove on us. But neither should we allow the false narrative of failure to take hold. We should be clear-eyed about what our military has accomplished, can accomplish, and the costs, risks, and potential gains in using force. Armed conflict will remain a necessary tool for the United States. We need to adapt our military to meet and defeat the challenges of the future, and we need to balance and incorporate military power into our global strategies appropriately — but that will not happen if we do it based on an incorrect understanding of the past.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.

Syrian Detente Worthless As Country Still Harbors Terrorists

Syrian overtures to broker a detente with the United States and de-escalate with Israel have turned out to be hollow, thanks to…

Trump warns Israel about interference in Syria after deadly raid, airstrikes

The Trump administration has worked diligently to help stabilize Syria in the wake of its December 2024 conquest by Islamic terrorists.

The administration has, for instance, removed sanctions and dropped the $10 million bounty on Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa, the al-Qaeda-linked terrorist who is also known as Muhammad al-Jawlani; terminated the Syria sanctions program; revoked the Foreign Terrorist Organization designation of al-Sharaa’s terrorist organizations al-Nusrah Front and HTS on July 8; and flooded parts of the war-torn country with humanitarian aid.

The recent Israeli attacks in the south of the country have prompted concerns among some in the administration, including the president, about the tenability of sustained peace in the region.

‘We are trying to tell Bibi he has to stop this.’

President Donald Trump reiterated his support for al-Sharaa on Monday and suggested that Israel should refrain from further interference.

“The United States is very satisfied with the results displayed, through hard work and determination, in the Country of Syria,” wrote the president. “We are doing everything within our power to make sure the Government of Syria continues to do what was intended, which is substantial, in order to build a true and prosperous Country.”

RELATED: ‘Begin repatriating’: German chancellor admits it’s time to give Syrian migrants the boot

President Donald Trump shaking hands with Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa. Photo by Syrian Presidency/Anadolu via Getty Images

President Donald Trump shaking hands with Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa. Photo by Syrian Presidency/Anadolu via Getty Images

“It is very important that Israel maintain a strong and true dialogue with Syria, and that nothing takes place that will interfere with Syria’s evolution into a prosperous State,” continued Trump. “The new President of Syria, Ahmed al-Sharaa, is working diligently to make sure good things happen, and that both Syria and Israel will have a long and prosperous relationship together.”

Two senior U.S. officials reportedly told Axios that the administration is concerned that repeated strikes inside Syria — including Israel’s bombing of Syrian forces in July — serve to undermine hopes of an Israel-Syria security agreement.

Israeli troops reportedly killed 13 people, injured dozens, and arrested several individuals during a raid in Southern Syria on Friday, some footage of which Israeli military spokesperson Avichay Adrae shared online.

The Israel Defense Forces indicated that the purpose of the operation was “to apprehend suspects from the Jaama Islamiya terrorist organization operating in the Beit Jinn area of southern Syria” and claimed that “during the activity several armed terrorists opened fire at the troops. IDF soldiers responded with live fire, supported by aerial assistance.”

The Syrian foreign ministry characterized the attack as a “full-fledged war crime” and claimed that the raid and corresponding airstrikes left more than 10 civilians dead including women and children.

Walid Akasha, a local official in the area, told Reuters, “We’re a peaceful, civilian population, farmers. We have a legitimate right to defend ourselves. We didn’t attack them first — they came onto our land.”

One of the U.S. officials told Axios, “The Syrians were going nuts. Their own constituents demanded retaliation because Syrian civilians were killed.”

According to the officials, Israel neglected to notify the White House or Syria of the operation in advance.

“We are trying to tell Bibi he has to stop this because if it continues he will self-destruct — miss a huge diplomatic opportunity and turn the new Syrian government to an enemy,” said one official, referring to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Netanyahu praised the Israeli soldiers involved in the Friday raid and noted in a statement on Tuesday, “After October 7th, we are determined to defend our communities on our borders, including the northern border, and to prevent the entrenchment of terrorists and hostile actions against us, to protect our Druze allies, and to ensure that the State of Israel is safe from ground attack and other attacks from the border areas.”

“What we expect Syria to do, of course, is to establish a demilitarized buffer zone from Damascus to the buffer zone area, including, of course, the approaches to Mount Hermon and the summit of Mount Hermon,” continued Netanyahu. “We hold these territories to ensure the security of the citizens of Israel, and that is what obligates us.”

The prime minister suggested further that in a “good spirit and understanding of these principles, it is also possible to reach an agreement with the Syrians.”

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Kuya Kim shares birthday wish on ‘TiktoClock’: ‘I’d like for the memory of Emman to continue’ January 23, 2026

- BTS to hold free comeback concert in Seoul come March January 23, 2026

- Boobay, ‘currently stable” at ‘in good condition” matapos mag-collapse sa stage sa Oriental Mindoro January 23, 2026

- TikTok seals deal for new US joint venture to avoid American ban January 23, 2026

- Pro coaches Jerry Yee, Aying Esteban allowed to call shots as head coaches in the NCAA January 23, 2026

- NBA: Kawhi Leonard stars in return as Clippers down Lakers January 23, 2026

- NBA: Shaedon Sharpe’s big 2nd half sends Blazers past Heat January 23, 2026