Category: Entertainment

THEN GIVE UP YOUR MANSION! X Users Torch Eilish for ‘Stolen Land’ Comment [WATCH]

Pop star Billie Eilish is facing a wave of online blowback after using her Song of the Year moment at the Grammy Awards to denounce immigration enforcement.

Trump Announces Kennedy Center Closing on July 4 for Two Years for Renovations

President Trump announced that the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., will be closing later this year on July 4 due to renovations.

The post Trump Announces Kennedy Center Closing on July 4 for Two Years for Renovations appeared first on Breitbart.

Bruce Springsteen Performs His Anti-ICE Song at Minneapolis Show: ‘Sometimes You Have to Kick Them in the Teeth’

Leftist rocker Bruce Springsteen hit the stage at Rage Against the Machine frontman Tom Morello’s concert in Minneapolis to perform his new anti-ICE and anti-Trump protest song for the first time on Friday.

The post Bruce Springsteen Performs His Anti-ICE Song at Minneapolis Show: ‘Sometimes You Have to Kick Them in the Teeth’ appeared first on Breitbart.

Breitbart • Documentary • Entertainment • John Nolte • Media • Politics

Nolte: Rotten Tomatoes — Audiences Rave for ‘Melania’ with 98% Rating While Bitter Critics Try to Destroy It

As of this writing, Melania, a documentary about First Lady Melania Trump, which has already taken the box office crown for the best documentary opening weekend in a decade, has a six percent rotten score over at Rotten Tomatoes. The Normal People score, however, sits at 98 percent fresh.

The post Nolte: Rotten Tomatoes — Audiences Rave for ‘Melania’ with 98% Rating While Bitter Critics Try to Destroy It appeared first on Breitbart.

box office • Breitbart • Documentary • Entertainment • Media • Politics

Nolte: ‘Melania’ Humiliates Media, Exceeds Expectations with Best Documentary Box Office Opening in Decade

The legacy media are eating crow once more now that Melania has scored the best box office opening for a documentary in a decade.

The post Nolte: ‘Melania’ Humiliates Media, Exceeds Expectations with Best Documentary Box Office Opening in Decade appeared first on Breitbart.

Blaze Media • Culture • Entertainment • Lifestyle • Movies • Supergirl

How Hollywood tries to masculinize femininity — and makes everyone miserable

We are told, repeatedly, that woke is dead. Piers Morgan even wrote a book about it, so it must be true. Right?

Wrong.

Strength, by Hollywood’s current definition, must weigh a little over 100 pounds and look perpetually annoyed.

If in doubt, please watch the trailer for “Apex,” due for release in April. With it comes Hollywood’s most exhausted fantasy yet: the indestructible badass woman who outruns youth, outpunches men twice her size, and shrugs off biology like it’s a clerical error.

Mission: Implausible

This time, it’s a 50-year-old Charlize Theron sprinting through the Australian wilderness and scaling cliffs as if she’s Tom Cruise circa “Mission: Impossible 2.” Gravity is optional. Muscle mass is negotiable. Aging, it seems, is strictly forbidden.

We’ve seen this act so many times that it barely registers any more. Swap the title card, rotate the backdrop, keep the same choreography. A lone woman wronged by men. A past trauma. An axe to grind, sometimes literally. Six-foot brutes wait their turn to be neutralized. The music swells. The credits roll. And with them go the eyeballs of nearly every viewer still capable of respecting basic reality.

The point is not that women can’t be strong. Of course they can. Strength is not the issue. Hollywood’s definition of it is. Somewhere along the way, empowerment became synonymous with women cosplaying male action heroes, only with fight scenes that insult Newton and scripts that insult the audience. A petite actress body-checking men built like refrigerators — then calling disbelief misogyny — is not progress.

What makes “Apex” more revealing than irritating is how nakedly it exposes the broader frame. This isn’t about one film or one actress. It’s the result of a steady drip: years of female-driven nonsense poured into every genre until it became the genre. The same beats. The same postures. The same lectures delivered at gunpoint.

Form fatale

Hollywood has always run on formula. Nothing new there. It followed money, copied hits, and abandoned failures without sentimentality. But the formula answered to the audience. If people didn’t buy tickets, the trend was over.

Now the industry treats audience resistance not as feedback, but as something to be corrected — like a behavioral problem that needs retraining. Failure is no longer evidence that the formula is broken. It is treated as proof that the audience is.

Studios like to pretend this is audience demand. It isn’t. It’s institutional inertia. Executives terrified of being accused of regression keep recycling the same safe lie: If the movie fails, the audience is at fault. If it succeeds modestly, it’s a cultural victory.

It’s a system that makes the arrival of the new “Supergirl” later this year entirely predictable. Not because audiences asked for it. Not because there was pent-up demand. Not because anyone ever thought, yes, this is what’s missing. It is arriving because this is what the industry now produces by reflex.

The irony is hard to miss. The original “Supergirl” debuted in 1984, the same year Orwell warned us about systems that repeat lies until they feel inevitable. That film was a commercial and critical dud, quickly forgotten for good reason.

Four decades later, Hollywood appears determined to rerun the experiment, convinced that time, tone, and audience memory can all be overwritten. Don’t expect to be entertained. Expect scowls and sermons in spandex. Strength, by Hollywood’s current definition, must weigh a little over 100 pounds and look perpetually annoyed.

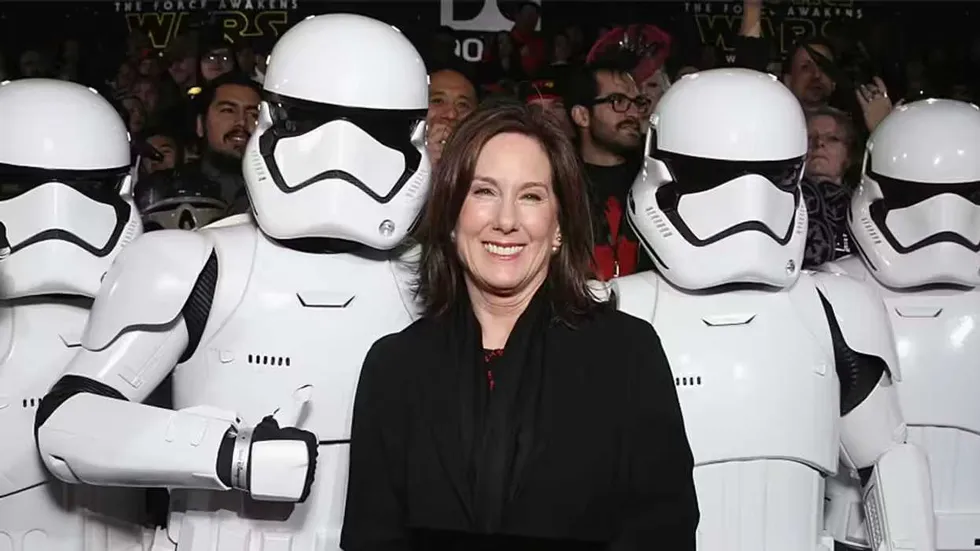

RELATED: FEMPIRE STRIKES BACK: Kathleen Kennedy leaves ‘Star Wars’; is it too soon for fans to celebrate?

Down for the count

We saw the results late last year. The box-office face-plant of “Christy,” the biopic of boxer Christy Martin, made the point brutally clear. Despite opening in more than 2,000 theaters, it scraped together just $1.3 million — one of the worst wide releases on record.

The film stars Sydney Sweeney, an American beauty inexplicably styled like a discount Rocky Balboa. Producers assumed her star power would draw crowds, then forgot why anyone — especially male viewers — watches her in the first place. It isn’t to see her absorb jabs, hooks, and uppercuts like a human heavy bag. It’s when she leans into what she actually is: feminine, magnetic, sexy. No one is buying a ticket to watch a gorgeous woman get beaten senseless.

This is the quiet truth studios refuse to say out loud: Men and women are not the same, and they do not want the same things on screen. Audiences happily watched Liam Neeson bulldoze Europe in “Taken.” They turned up in droves to see Keanu Reeves turn the death of a dog into a four-film genocide in “John Wick.” Nothing motivates a man like canine-related trauma and unlimited ammunition. Those films worked because they leaned into male fantasy without apology.

Equalizer rights?

What audiences don’t want is that same template awkwardly stapled onto a completely different body and sold as innovation. Denzel Washington was excellent in “The Equalizer” — cold, credible, and infinitely cool.

The TV reboot took that precision and desecrated it by turning the role into unintentional slapstick. A morbidly obese Queen Latifah as a silent, unstoppable angel of death is pure absurdity. This is a woman who struggles to climb a single flight of stairs, yet viewers are expected to believe she’s capable of stalking, subduing, and dispatching trained men without breaking a sweat.

Which brings us back to “Apex.” What makes the film accidentally hilarious isn’t Charlize Theron running through the bush. It’s the industry sprinting right behind her, desperately chasing a fantasy that stopped selling years ago. The humor comes from the sincerity. From the absolute faith that this time — finally — it will land.

And it will land. Just not gracefully. More like a Boeing falling out of the sky. Twisted metal, scorched wreckage, and stunned executives wandering around asking what went wrong.

And from that wreckage, there will be no reckoning. No pause. No course correction. Just a quick trip back to the studio lot to greenlight the next movie nobody requested and that everyone will forget.

Nolte: Disgraced Former CNN Anchor Don Lemon Arrested for Church Riot

Don Lemon, a disgraced former CNN anchor, was arrested Thursday night in Los Angeles, according to news reports.

The post Nolte: Disgraced Former CNN Anchor Don Lemon Arrested for Church Riot appeared first on Breitbart.

Exclusive – First Lady at ‘Melania’ Premiere: Film Shows ‘My Incredible Busy Life’

First Lady Melania Trump discussed her documentary Melania with Breitbart News at the world premiere, saying the film will show her “incredible busy life.”

The post Exclusive – First Lady at ‘Melania’ Premiere: Film Shows ‘My Incredible Busy Life’ appeared first on Breitbart.

Exclusive — Trump on Already Holding More Cabinet Meetings Than Biden: ‘There’s Never Been an Administration so Transparent as This One’

President Trump spoke with Breitbart News at the Trump-Kennedy Center’s red carpet world premiere of the new Melania documentary, saying his administration was more transparent than the last and pointing to lower gas prices, economic strength, and falling crime.

The post Exclusive — Trump on Already Holding More Cabinet Meetings Than Biden: ‘There’s Never Been an Administration so Transparent as This One’ appeared first on Breitbart.

LATE-NIGHT LECTURE: Colbert Says ICE Worse Than Nazis Because at Least Nazis Were ‘Willing to Show Their Faces’ [WATCH]

Late-night host Stephen Colbert drew backlash this week after a remark about Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol agents that critics argued trivialized history while escalating rhetoric around immigration enforcement.

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026

![68th GRAMMY Awards - Show THEN GIVE UP YOUR MANSION! X Users Torch Eilish for ‘Stolen Land’ Comment [WATCH]](https://hannity.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/GettyImages-2259492778-300x200.jpg)

![colbert LATE-NIGHT LECTURE: Colbert Says ICE Worse Than Nazis Because at Least Nazis Were ‘Willing to Show Their Faces’ [WATCH]](https://hannity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/colbert-300x166.png)