Category: Tariffs

What Georgia’s Film Tax Credits and Trump–Biden Tariffs Have in Common

Industrial policy is failing, and not just in Washington. Across America, officials promise to engineer the right economic outcomes by…

Breitbart • Donald Trump • Iran • Israel / Middle East • Politics • Tariffs

Trump Slaps 25 Percent Tariff on Any Country Doing Business with Iran

President Donald Trump on Monday shared that he is placing a 25 percent tariff on any country that does business with Iran.

The post Trump Slaps 25 Percent Tariff on Any Country Doing Business with Iran appeared first on Breitbart.

Roomba maker iRobot files for bankruptcy, putting it in Chinese hands

Autonomous vacuums could go extinct unless they are made in the United States.

This is the harsh reality affecting companies like iRobot, the creator of Roomba, which just filed bankruptcy.

‘… with no anticipated disruption to its app functionality.’

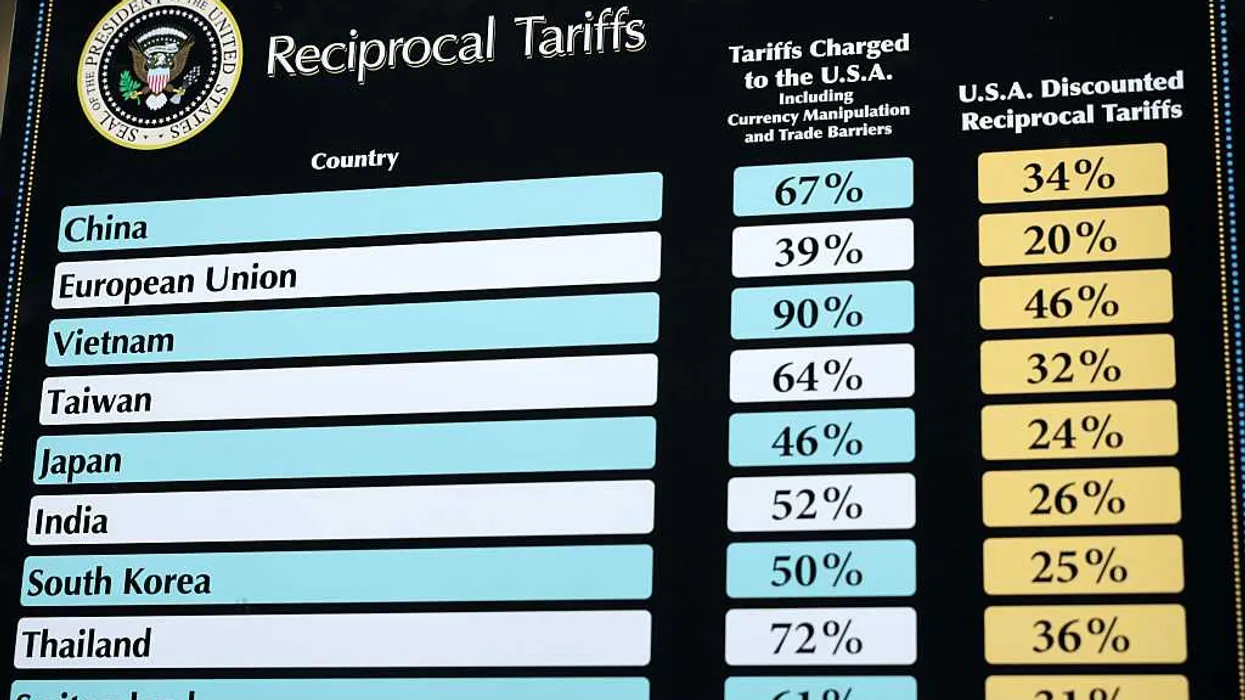

Despite the company generating over $680 million in 2024, iRobot has been crippled by U.S. tariffs. Due to a 46% import tariff on Vietnam, iRobot’s costs were raised by $23 million in 2025, according to Reuters, which reviewed the court filings.

The court filings also reportedly noted that while Roomba is still dominating in U.S. and Japanese markets, it lost too much money on price reductions and investments in technological upgrades in order to maintain pace with its competitors.

According to the Verge, the company said it will continue to operate “with no anticipated disruption to its app functionality, customer programs, global partners, supply chain relationships, or ongoing product support.”

Simply put, after more than 20 years on the market, the Roomba is able to operate without online connectivity.

The bankruptcy will put iRobot under Chinese control moving forward, with the manufacturing company that controls its debt.

RELATED: The ultimate Return guide to escaping the surveillance state

Photo by: Andrew Lipovsky/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

Photo by: Andrew Lipovsky/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

Court documents reportedly showed that Picea, a Chinese manufacturer, purchased iRobot while taking its debt on board, which is estimated to be about $190 million. The vacuum company took on the debt in 2023 to refinance its operations, Reuters claimed.

The debt came even after Amazon paid a $94 million termination fee after backing out of a $1.7 billion acquisition deal in 2024, according to the New York Times.

It has not been that long since iRobot had a massive market value at $3.56 billion in 2021; it is now estimated to be worth just $140 million.

New owners Picea will take 100% ownership of the company and cancel the $190 million in debt, while also canceling a $74 million debt that iRobot owed through a manufacturing agreement.

RELATED: The AI takeover isn’t coming — it’s already here

Not only did iRobot need to deal with Vietnamese tariffs, other manufacturing that was established in Malaysia in 2019 was also likely affected.

It was not announced that Roomba had cut manufacturing from the country, and if it remained, would likely have been subjected to a 24% tariff rate from the Trump administration, which included taxing machinery and electronics.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Economists Complain About Trump’s New Inflation Figures

It isn’t the data they don’t like — it’s the results — lower inflation and higher real wages. The “affordability…

Blaze Media • Opinion & analysis • Tariffs • Taxes • Trade policy • Trump

Is a tariff a tax?

Is a tariff a tax? Many Americans have forgotten that this question, which has been in the news more or less all year, was fundamental to the American Revolution. And among American Patriots, or Whigs, meaning those who supported the colonists’ claims against Parliament, there was almost universal consensus that they were different things, constitutionally speaking.

Throughout the Imperial Crisis of 1763 to 1776, the consensus among the colonists was that Parliament had the right to regulate trade in the British Empire but had no right to tax the colonists. And they recognized that a regulation of trade might take the form of a duty imposed upon, for example, molasses imported from French colonies to favor molasses imported from British colonies.

The founding generation believed in the separation of powers.

In the colonists’ view, the Sugar Act of 1764 was an unconstitutional innovation. The Act was quite explicit, stating at the top that it was passed for the purpose of “applying the produce of such duties, and of the duties to arise by virtue of the said act, towards defraying the expences of defending, protecting, and securing the said colonies and plantations.” It was the first trade act to do that.

Townshend’s overreach

The Stamp Act of 1765, and the reaction to it, made the protest against the 1764 Sugar Act less conspicuous. The result of the actions taken against the Stamp Act was that many in Parliament did not grasp the American argument against the Sugar Act. Hence, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in 1767, imposing duties on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea to raise revenue. When the colonists complained, many in Parliament accused the colonists of moving the goalposts.

The charge was not accurate, but it did reflect what they believed. And, like many today, many members of Parliament were unable to grasp the difference between a duty imposed for the purpose of trade regulation and a duty imposed for the purpose of raising revenue.

The most famous criticism of the Townshend Acts, and the most popular writing of the era until Thomas Paine published “Common Sense” in January 1776, was John Dickinson’s “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania.” In the second letter, Dickinson made the consensus Patriot argument logically, clearly, and eloquently.

There is another late act of parliament, which appears to me to be unconstitutional, and as destructive to the liberty of these colonies, as that mentioned in my last letter; that is, the act for granting the duties on paper, glass, etc.

The parliament unquestionably possesses a legal authority to regulate the trade of Great Britain, and all her colonies. Such an authority is essential to the relation between a mother country and her colonies; and necessary for the common good of all …

I have looked over every statute relating to these colonies, from their first settlement to this time; and I find every one of them founded on this principle, till the Stamp Act administration.* All before, are calculated to regulate trade, and preserve or promote a mutually beneficial intercourse between the several constituent parts of the empire. … The raising of a revenue thereby was never intended. … Never did the British parliament, till the period above mentioned, think of imposing duties in America for the purpose of raising a revenue. …

Here we may observe an authority expressly claimed and exerted to impose duties on these colonies; not for the regulation of trade; not for the preservation or promotion of a mutually beneficial intercourse between the several constituent parts of the empire, heretofore the sole objects of parliamentary institutions; but for the single purpose of levying money upon us.

This I call an innovation; and a most dangerous innovation.* It may perhaps be objected, that Great Britain has a right to lay what duties she pleases upon her exports.

That so many people today don’t seem to understand this distinction is a sign that the American bar seems to have gone Tory. The founding generation’s way of thinking about tariffs, and perhaps law in general, is in danger of being rendered foreign to our public policy discussion, perhaps even to constitutional discussion, even among people who mistakenly think of themselves as originalists.

This way of thinking, of course, says little about the current case, as the purpose of the law itself must be understood in light of the thinking of the men who passed it. But it is also true that the way of thinking that Dickinson represented, and which was broadly shared in the founding generation, might have something to say here.

Delegation’s limits

The founding generation believed in the separation of powers. The founders recognized, as “The Federalist” notes, that in practice the powers will inevitably overlap and sometimes clash. But they did operate within a way of legal and constitutional thinking that took it as a given that in order to guard the separation of powers, any delegation of legislative powers to the executive had to be limited and focused.

There is a difference between a reasonable and an unreasonable delegation of powers, just as there is between a tax and a regulation of trade, even if, in both cases, money is raised at customs houses. The kind of delegation the Trump administration is asserting in this case is difficult, perhaps impossible, to reconcile with the practice of separation of powers. Congress has no right to abdicate its obligation to set trade policy via legislation.

RELATED: Read it and weep: Tariffs work, and the numbers prove it

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The Trump administration’s assertion that it has the right to set tariffs worldwide, claiming unlimited emergency power based on a law designed to delegate to the president a narrow emergency power, resembles the kind of expansive, arbitrary interpretation that the founders’ legal heroes fought.

In the 1630s, King Charles claimed the right to collect “ship money” throughout England. By tradition, the king had the right to raise money, without Parliament’s consent, in port towns in time of war, or if war was imminent.

King Charles asserted a living constitution interpretation: Given modern circumstances, he claimed a general right to raise taxes if a war emergency was imminent. Dickinson mentioned the case in the first Farmer’s Letters, suggesting there was a connection between the logic of the one argument and the other.

Our difficulty recognizing the limits of the nondelegation doctrine — and our confusion about the difference between a duty imposed to raise revenue and one imposed to regulate trade — shows how much work remains if we want to understand the Constitution as the framers did. That understanding requires grappling with the ideas about human nature, government, and law that justified ratification in the first place and that still anchor our constitutional order.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.

Fed Study Vindicates Trump Trade Policy: 150 Years of Evidence Shows Tariffs Lower Inflation

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco examined major tariff changes from 1870 through 2020 across the United States, United Kingdom, and France. Their conclusion challenges the conventional wisdom that dominated economic policy debates in recent years: when countries raise tariffs, prices actually fall, not rise.

The post Fed Study Vindicates Trump Trade Policy: 150 Years of Evidence Shows Tariffs Lower Inflation appeared first on Breitbart.

The Answer to Republicans’ ‘Affordability Problem’? Unleash Supply.

The Nov. 4 election results are a reality check for the Trump administration. Democrats didn’t just run up the score…

PAYBACK PLAN: Trump Proposes $2K ‘Tariff Dividend’ for Millions of Americans

President Trump wants to turn tariffs into cash for Americans — literally.

Alan Dershowitz Shares What He Wishes Trump’s Lawyers Had Done Differently Arguing Tariffs Before Supreme Court

‘it may give to Congress the power’

Auto industry • Blaze Media • Donald Trump • Lifestyle • Mexico • Tariffs

Trump’s SHOCKING 25% truck tariff: A matter of national security?

President Donald Trump’s dropping another tariff on the auto industry.

Starting November 1, the U.S. will impose a 25% tariff on all imported medium- and heavy-duty trucks, a dramatic escalation in the administration’s ongoing effort to strengthen domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on foreign-built vehicles.

The short-term effects could include delays in vehicle availability, higher fleet costs, and potential retaliation from trading partners.

This announcement sent shockwaves through global trade circles and Wall Street. According to Trump, the decision is rooted in national security and economic strength, not politics. But as with any sweeping trade action, there’s more under the hood than meets the eye.

Priced to move

While celebrating the immediate bump in automaker stock prices following the tariff announcement, Trump’s message was direct. “Mary Barra of General Motors and Bill Ford of Ford Motor Company just called to thank me. … Without tariffs, it would be a hard, long slog for truck and car manufacturers in the United States.”

The president framed the move as a matter of economic sovereignty, arguing that domestic production capacity in critical industries, like heavy vehicles used in logistics, defense, and infrastructure, is essential to national security.

That message resonates with many Americans frustrated by decades of outsourcing and the hollowing out of domestic manufacturing. But it’s also raising concerns among global partners and major U.S. companies with deep supply chain ties abroad.

Winners and losers

The new tariffs target a wide range of vehicles: delivery trucks, garbage trucks, utility vehicles, buses, semis, and vocational heavy trucks.

Manufacturers expected to benefit include Paccar, the parent company of Peterbilt and Kenworth, and Daimler Truck North America, which produces Freightliner vehicles in the U.S. These companies have much to gain from reduced import competition and potentially stronger domestic demand.

However, for companies like Stellantis, which manufactures Ram heavy-duty pickups and commercial vans in Mexico, the impact could be costly.

Under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, trucks assembled in North America can move tariff-free if at least 64% of their content originates within the region. But many manufacturers rely on imported parts and materials, putting them at risk of higher costs and tighter margins.

Mexico, the largest exporter of medium- and heavy-duty trucks to the U.S., will be hit hardest. Imports from Mexico have tripled since 2019, climbing from about 110,000 to 340,000 units annually. Canada, Japan, Germany, and Finland also face new barriers under the 25% tariff.

Industry pushback

Not everyone is excited about the tariffs — especially considering that the import sources for these trucks (Mexico, Canada, and Japan) are long-standing American allies and trading partners.

Industry analysts warn of supply-chain disruptions, potential price increases, and reduced model availability for both commercial fleets and consumers. Tariffs could also pressure U.S. companies to adjust production strategies, increase domestic sourcing, or even pass higher costs on to customers.

RELATED: Hemi tough: Stellantis chooses power over tired EV mandate

Chicago Tribune/Getty Images

Chicago Tribune/Getty Images

The politics of protectionism

This is not the first time a Trump administration has leaned on tariffs as an economic lever. During his previous term, tariffs on imported steel, aluminum, and Chinese goods aimed to bring manufacturing back to U.S. soil. Supporters argue those policies helped revitalize key industries and encourage job growth. Critics countered that they raised costs for American companies and consumers alike.

Still, there’s no denying that tariffs remain one of Trump’s most powerful economic tools and one of his most politically effective messages. By positioning tariffs as a way to protect American jobs, the policy appeals to workers and manufacturers across the Rust Belt, a region that will play a pivotal role in the upcoming election.

Short-term pain

For the U.S. trucking and logistics sectors, the short-term effects could include delays in vehicle availability, higher fleet costs, and potential retaliation from trading partners.

Truck leasing and rental companies that rely on imported chassis and components may see their operating costs rise. Meanwhile, domestic truck makers could ramp up production, potentially benefiting U.S. suppliers and job growth in states like Ohio, Michigan, and Texas.

The challenge will be whether domestic manufacturers can meet demand quickly enough without triggering inflationary pressures in the commercial transportation market.

Long-term gain?

Trump’s framing of the tariffs as a “national security matter” echoes earlier policies aimed at reducing foreign dependence in critical sectors, from semiconductors to electric vehicles. Advocates say this approach ensures that America can produce what it needs in times of crisis.

But opponents warn that labeling economic measures as “security” issues can backfire, alienating allies and inviting retaliation. European officials and trade negotiators in Canada and Japan are already signaling possible countermeasures if talks with Washington fail to yield exemptions.

Mind the gap

The real question now is how manufacturers will adapt. Companies may accelerate plans to localize assembly and parts production inside the U.S., while foreign brands could seek joint ventures or partnerships with American firms to skirt tariffs.

Consumers and fleets will likely see higher sticker prices for imported trucks and commercial vehicles as tariffs ripple through supply chains. That may also shift more buyers toward U.S.-built models, at least in the short term.

Ultimately, Trump’s move puts America’s industrial policy back in the driver’s seat. Whether it strengthens the economy or creates new trade turbulence will depend on how quickly domestic production can fill the gap left by imports.

President Trump’s 25% truck tariff is a high-stakes bet on American manufacturing dominance. It could fuel a resurgence in U.S. production or ignite new rounds of trade retaliation.

Either way, one thing is certain: The decision has already reshaped the conversation about what it means to build, and buy, American.

search

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026