Category: Lifestyle

Abide • Blaze Media • Christianity • Conversion • Faith • Lifestyle

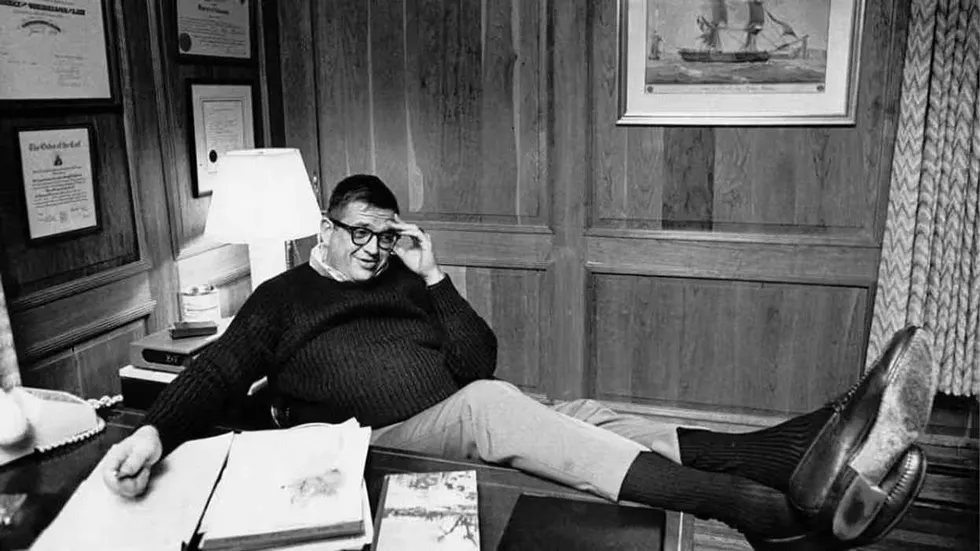

Malcolm Muggeridge: Fashionable idealist turned sage against the machine

“The depravity of man is at once the most empirically verifiable reality and the most intellectually resisted fact.”

The name of the man who made this pronouncement may not mean much to many readers now. Yet the world he warned about has arrived all the same, whether his name is remembered or not.

When Malcolm Muggeridge — a British journalist and broadcaster who became a public figure in his own right — died in 1990, many of his fears still felt abstract. The moral strain was visible, but the structure was holding. Progress was spoken of with confidence, and freedom still sounded uncomplicated.

‘I never knew what joy was until I gave up pursuing happiness.’

Today, those assumptions lie in pieces. What he distrusted has hardened into dogma. What he questioned has become unquestionable. We are living amid the consequences of ideas he spent a lifetime probing.

Theory meets reality

Muggeridge was never dazzled by modern promises. He distrusted grand schemes that claimed to perfect humanity while refusing to reckon with human nature. That suspicion wasn’t a pose; it was learned. As a young man, he flirted with communism, drawn in by its certainty and its language of justice. Then he went to Moscow. There, theory met reality.

What he encountered was not liberation but deprivation. Hunger was rationalized as hope. Cruelty came wrapped in benevolent language. Compassion was loudly proclaimed and quietly absent. The experience cured him of fashionable idealism for life. It also taught him something harder to accept: Evil often enters history announcing itself as virtue, and the most dangerous lies are told with complete sincerity.

That lesson stayed with him. In an age once again thick with certainty, that insight feels uncomfortably current.

Pills and permissiveness

Yet Muggeridge’s critique extended beyond politics. At heart, he believed the modern crisis was spiritual. God had become an embarrassment, sin a diagnosis, and responsibility something to be displaced by grievance. Pleasure, once understood as a byproduct of order, was recast as life’s purpose. The result, he argued, wasn’t freedom but loss.

This realism shaped his opposition to the sexual revolution. Long before its consequences were obvious, he warned that freedom severed from restraint wouldn’t liberate people so much as hollow them out. He mocked the belief that pills and permissiveness would deliver happiness. What he anticipated instead was loneliness, instability, and a culture increasingly medicated against its own dissatisfaction.

Muggeridge also understood the media with unsettling clarity. As a journalist and broadcaster, he watched newsrooms trade substance for spectacle and truth for approval. When entertainment becomes the highest aim, he warned, reality soon becomes optional.

By the end of his career, Muggeridge had dismantled nearly every modern promise. Fame proved thin. Desire disappointed. Professional success brought no lasting peace. Skepticism could clear the ground, but it could not explain why nothing worked.

A skeptic stands down

When after more than a decade of exploring Christianity, Muggeridge finally entered the Catholic Church in 1982, the reaction among his peers was disbelief bordering on embarrassment. This was not the impulse of a sentimental seeker but of one of Britain’s most famous skeptics — a man who had mocked piety, distrusted enthusiasm, and made a career of puncturing illusions.

Friends assumed it was a late-life affectation, a theatrical flourish from an aging contrarian. Muggeridge himself knew better. He had not converted because Christianity felt safe or consoling, but because, after a lifetime of alternatives, it was the only account of reality that still made sense.

As he had written years before in “Jesus Rediscovered,” “I never knew what joy was until I gave up pursuing happiness.”

That sentence captures the logic of his conversion. Muggeridge did not arrive at faith through nostalgia or temperament. Christianity did not flatter him. It named pride, lust, and cruelty plainly, then offered grace without euphemism. It explained the world he had already seen — and himself within it.

RELATED: Chuck Colson: Nixon loyalist who found hope in true obedience

Washington Post/Getty Images

Washington Post/Getty Images

Truth endures

His Catholicism was not an escape from seriousness but its culmination. He believed human beings flourish within limits, not without them; that desire requires direction; that pleasure without purpose corrodes. Christianity endured, he argued, not because it was comforting but because it was true.

After his conversion, Muggeridge did not soften. He sharpened. The satire retained its bite. The warnings grew more direct. But they were no longer merely critical. Skepticism had given way to clarity — not because he had abandoned reason, but because he had finally stopped pretending it was enough.

More than three decades after his death, Muggeridge’s voice sounds less like commentary than like counsel. The world he warned about has arrived. What remains is the stubborn relevance of faith grounded in reality — and the freedom that comes only when truth is faced, rather than fled.

EPA to California: Don’t mess with America’s trucks

For decades, California has used its enormous market power to shape national vehicle policy, often pushing regulations far beyond its borders and into the daily lives of Americans who never voted for them. That long-running dynamic has now reached a critical moment.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is moving to block California’s latest attempt to regulate heavy-duty trucks nationwide — a proposal first announced in 2025 but now entering a decisive phase of federal review.

California’s early emissions standards helped accelerate cleaner engines and better fuel systems. But leadership can turn into compulsion.

With final EPA action expected in 2026, the outcome will determine whether California can continue using its borders as a regulatory choke point for interstate trucking, or whether federal limits will finally be enforced.

Freight fright

At issue is California’s Heavy-Duty Inspection and Maintenance requirement, part of the state’s air-quality plan. The rule would apply not only to trucks registered in California, but to any heavy-duty vehicle operating within the state — including those registered elsewhere in the U.S. or even abroad. In practical terms, a truck hauling goods from Texas, Ohio, or Mexico could be forced to comply with California’s rules simply by crossing its borders.

The EPA has proposed disapproving that requirement, citing serious constitutional and statutory concerns.

This matters far beyond California. Heavy-duty trucks are the backbone of the American economy, moving food, fuel, medicine, building materials, and consumer goods across state lines every day.

Regulations that raise costs or restrict access for those vehicles ripple through supply chains and ultimately show up as higher prices at the checkout counter — including for online purchases. The EPA’s proposed action acknowledges that reality and draws a clear line between environmental policy and unlawful overreach.

Out of line

According to the agency, California’s proposal appears to violate the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which prevents individual states from interfering with interstate trade. The Clean Air Act also requires state implementation plans to comply with federal law, and the EPA argues California’s approach fails that test. By attempting to regulate out-of-state and foreign-registered vehicles, California stepped into territory reserved for the federal government.

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin has been blunt in explaining the agency’s position. California, he has argued, was never elected to govern the entire country, yet its regulatory ambitions — often justified in the name of climate policy — have imposed higher costs on Americans nationwide. Allowing one state to dictate trucking standards for the rest of the country undermines both federal law and economic stability.

Foreigners too

There is also a foreign-commerce issue that rarely gets discussed. California’s rule would apply to vehicles registered outside the United States, even though authority over foreign trade and international relations rests exclusively with the federal government. That alone raised red flags and reinforced the EPA’s conclusion that the state exceeded its legal authority.

This proposed disapproval is part of a broader federal effort to rein in California’s emissions authority. In 2025, the Department of Justice filed complaints against the California Air Resources Board, arguing that the state was effectively enforcing pre-empted federal standards through informal agreements with manufacturers. Together, these actions reflect growing concern in Washington that California has relied on market leverage rather than lawful authority to achieve national policy outcomes.

Waiver goodbye

Waivers are central to this conflict. For years, California received special permission under the Clean Air Act to set its own vehicle emissions standards, with other states allowed to follow its lead. Under the previous administration, the EPA granted waivers for California’s Advanced Clean Cars II, Advanced Clean Trucks, and Heavy-Duty Engine Omnibus NOx rules. Supporters framed them as environmental progress. Critics warned they would raise vehicle prices, limit consumer choice, strain the electric grid, and force changes the market was not ready to absorb — which is exactly what followed.

In June 2025, Congress overturned those waivers using the Congressional Review Act. That move sent a clear message: Vehicle standards should be national in scope, not dictated by a single state, regardless of its size or political influence. The EPA’s current review of California’s truck inspection rule builds directly on that message.

Supporters of California’s approach often point to the state’s historic role in improving air quality and advancing technology. That is true — up to a point. California’s early emissions standards helped accelerate cleaner engines and better fuel systems. But leadership can turn into compulsion, especially when it ignores regional differences, economic realities, and legal limits.

RELATED: Will Trump’s unconventional plan to stop the UN climate elites work?

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Recalibration

The heavy-duty truck sector makes this clear. Unlike passenger cars, trucks operate on thin margins and long replacement cycles. Fleet decisions are driven by reliability, infrastructure availability, and total cost of ownership. Mandating technologies before they are ready or widely supported does not accelerate progress; it creates higher costs and unintended consequences — especially when those mandates originate in a single state but affect national commerce.

The EPA’s move suggests that era may be nearing its end. By challenging California’s heavy-duty inspection requirement, the agency is asserting that environmental goals do not justify ignoring constitutional structure. Clean air matters — but so do the rule of law, economic practicality, and the free movement of goods across state lines.

The proposed disapproval remains open for public comment, after which the EPA is expected to take final action later this year. Whatever the outcome, the signal is unmistakable: Federal regulators are no longer willing to automatically defer to California when state ambition collides with national authority.

For truck drivers, fleet operators, manufacturers, and everyday consumers, this moment represents a recalibration. It reaffirms that vehicle regulation should be consistent nationwide — and that environmental policy works best when it respects both economic reality and the legal framework that holds the country together.

Blaze Media • Culture • Hollywood • Lifestyle • Screenwriting • Writing

You can’t be 50 in Hollywood

I had been living in New York for several years, writing young adult novels. But I wanted to move to Los Angeles. I needed a change of scenery, and I wanted to try screenwriting.

A friend connected me to a guy who had spent several years in L.A. pursuing film and TV writing. I called the guy and told him my plan.

The hair dye felt like it was burning my scalp. After I rinsed it out, my whole head glowed. Did it make me look younger? I guess it did. But it also made me look like a clown.

He said: “How old are you?”

I said 49.

He said, “That’s too old. You can’t be 50 in Hollywood. You’ll need to lie about your age.”

Then he asked me if I had gray hair. I said I did. He said I would need to dye it.

I said, “But George Clooney has gray hair. Doesn’t it look distinguished?”

He said I would definitely want to dye it. “Everyone dyes their hair in L.A. Get a good hairdresser.”

*******

He continued relating his experiences. He listed the dangers of Hollywood. They steal your ideas. They lie. They pretend to be your friend. I would need a good lawyer, and a manager, and an agent.

Most of this I already knew. But the “you can’t be 50 in Hollywood” part: I hadn’t heard that before.

Reelin’ In the Years

After we hung up, I thought about the age problem. I had already “adjusted” my age once while I was writing young adult novels.

I did this after attending a book festival, where I saw that all the other young adult authors were generally in their 20s and 30s. I was at least a decade older than most of them.

So I shaved five years off my Facebook age. Just in case anybody looked. And then I did the same thing when I filled out the publicity questionnaires for my publisher.

But the age problem got worse when I arrived in L.A. The first screenwriter I met with was 24 and looked like he was in high school. When I got home from that meeting, I went on Facebook and shaved three more years off my birthday.

When I did this, a little notice popped up, informing me that this would be the last time I would be allowed to change my birthday on Facebook.

So now, I was 41 according to Facebook, 44 according to my New York publisher, and 49 according to my driver’s license and the IRS.

This was a lot to keep track of. It made for some awkward moments on first dates.

Gray matters

It didn’t take long to realize that in Hollywood — where lying is considered “self-care” — what people really judged you on was your looks.

So then I considered my appearance. My hair was pretty gray. Should I try dyeing it?

I went to Ralphs and bought a box of Clairol Nice’n Easy hair dye. I went for espresso brown, which seemed closest to my original hair color.

I set up shop in my bathroom. I put on the gloves and followed the instructions on the box, mixing the chemicals and smearing them onto my head. It was a messy business.

The hair dye felt like it was burning my scalp. After I rinsed it out, my whole head glowed. Did it make me look younger? I guess it did. But it also made me look like a clown.

*******

I flew back to New York soon after, and a female friend immediately noticed the change. She said: “It’s true what they say; you look 10 years younger!”

That was nice to hear. But I was alarmed that she noticed it instantly. From 50 feet away.

Another friend didn’t believe me when I told her it was dyed. She had to look closer and touch it until she saw that I was telling the truth.

I was still trying to get used to it myself. Every time I saw my reflection, I startled myself. Who’s that guy with the dye job?

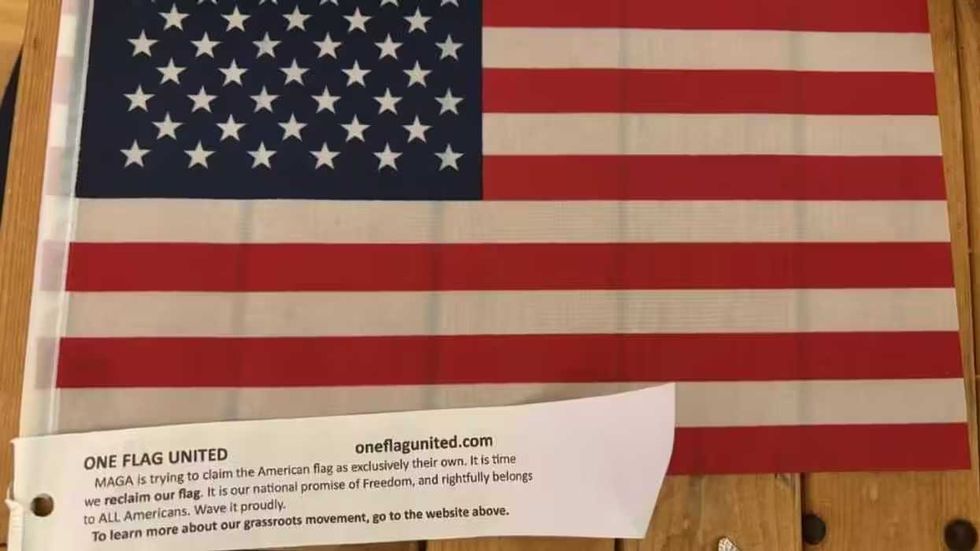

RELATED: The left wants to ‘reclaim’ the American flag; did they run out of lighter fluid?

Blake Nelson

Blake Nelson

Pro tips

Back in L.A., I spotted a sign in a hair salon near my apartment: “Dye and Haircut $80.” Maybe this was the solution: getting your hair dyed by a professional.

I would like to say this was a luxurious, pampering experience. It was not. The hairdresser roughed me up pretty good. And then I had to sit there for 40 minutes, in sight of people walking by the window, with a giant plastic covering over me and my thinning hair wrapped in tin foil.

And then, after all that, it looked no different from the Clairol dye job I had given myself for $9.99!

*******

Still, I stuck with it, re-dyeing it every six weeks — like it said on the box — for most of a year.

During this time, I kept a watchful eye out for other men with dyed hair. I was definitely not alone. At the beach, you would see aging “surfer dads” with dyed blonde hair and a skateboard under their arms. It wasn’t a terrible look. As long as you wore Vans and board shorts.

And of course, men who were on TV or acted in movies always dyed their hair. I’d see these men everywhere. Or I’d see guests on late-night talk shows who looked like they had just had it done an hour before. Their hair had that blurry, fresh-dye glow.

I became skilled at spotting dye jobs on either sex. I hadn’t realized how many women dyed their hair: basically all of them, after about 30.

The good news was that nobody thought less of a man for dyeing his hair. This was Los Angeles. Dyeing your hair meant you had a job.

All is vanity

This wasn’t the case on the East Coast. New York City was the land of the silver fox. Being a well-dressed, gray-haired, 50-year-old male was highly desirable. It meant you were rich!

In fact, it was in New York that a couple of female friends intervened and informed me that the hair-dye thing wasn’t working. I looked better being gray.

After that, my vanity took over, and when I returned to L.A., I shaved my head and released myself back into middle age.

Once I let myself go gray again, another Los Angeles acquaintance told me she thought I looked much better. She said the dye job made me look untrustworthy, like a used-car salesman.

*******

So that was a relief. But the real relief didn’t come until many years later, when I retired from writing and went back home to Portland and returned to total normalcy.

In retirement, I didn’t have to be young; I didn’t have to be cool. I could just be an old, gray-haired person like everybody else.

Though on Facebook — thanks to its birthday-changing restrictions — I remain a slightly younger and livelier version of myself.

Blaze Media • Fishing • Lifestyle • Norfolk • North sea • United kingdom

Fishing with my dying father

On the North Norfolk coast, dawn is more sensory than visual.

Sea lavender and samphire engulf you before the bite of the wind reminds you of nature’s power. As the sun rises above the horizon, my father and I cross the salt marshes, the light revealing tidal creeks winding through the mudflats. This time, though, I know it is our last trip together.

In angling, the tippet is the thinnest section of line, the point most likely to fail.

Every step is taken with the knowledge that these rituals — these early mornings, the scent of salt and wildflowers, the quiet companionship — are being performed for the final time.

Silence as stewardship

This is not just a landscape but a stage on which the story of my family unfolds. Each tradition echoes those who came before and those still to come. This place, and these shared customs repeated year after year, have woven our family history together — each visit another stitch in a tapestry stretched across generations.

There is no better place for solitude than Stiffkey, an idyllic village nestled in the Norfolk countryside. For miles around, the only sounds are wood pigeons cooing in the trees and the distant thunder of the sea. It is still very early — five in the morning — when we break this peace with the rhythmic punch of a shovel digging into saturated sand. My father and I do not speak as we work. Ours is a silence filled with meaning, a language shaped by years of tradition and respect for the world around us.

The rhythm of these mornings — the shared labor, the quiet companionship — blurs the boundaries between past and present, between father and son, creating a continuous thread running through my memory. Growing up, my father and I mainly communicated through the tension of a fishing line. Our family has never been big on talking; we are like frayed strings, bound and spliced together by tradition.

In the modern world, silence between two men is often treated as a void to be filled with noise. But on this stretch of coastline, silence is a form of stewardship. To be quiet is to respect the natural world. To be quiet together is to acknowledge a bond that does not require speech.

Here time folds in on itself — my father’s footsteps merging with his father’s, and mine with both of theirs.

Stiffkey blues

My father brought us to Stiffkey every year for our family holiday. For decades, this was his parish. He moved through the shifting terrain with the confidence of a man who knew the tide’s schedule like the back of his hand.

This time, watching him navigate the narrow ravines in the soft morning light, I see not the man who first guided me to the water 20 years earlier but his shadow. His light has dimmed — but it is still bright enough to guide us.

The lessons of Stiffkey are as much about patience, respect, and inheritance as they are about fishing. Each action — from digging bait to laying lines — forms a thread in the fabric of our shared history.

Laying fishing lines is a skill. The tide’s timing and direction determine how the lines must be slanted to catch fish. Digging your own bait matters too; no competent angler wants to carry unnecessary weight from home.

You take only what you need, while respecting the land and sea. From an early age, this was the lesson my father taught me: We are merely guardians, entrusted with care until it is time to pass things on.

“The ragworms aren’t biting,” I would tell him. He would approach with his antalgic gait, quietly move my shovel a few feet, and say, softly but with conviction, “Dig between the holes — that’s where they live.” Ten minutes later, the plastic bucket would overflow.

These moments bridge generations, passing down not just skill but belonging. This was where my grandfather taught my father to fish. Decades later, my father stood here teaching me.

A disused sewage pipe stretches northward, its end disappearing beneath the waves of the North Sea, marked only by a lone orange buoy. With an upturned wooden rake slung over my shoulder, its worn teeth piercing an old onion sack, I would walk the length of the pipeline. I can still feel the chill of rusted metal beneath my bare feet and my father’s watchful eyes — stern yet generous — urging me on. Together we raked the mudflats for cockles, the famed “Stiffkey blues,” once plentiful, now sought like hidden treasure.

RELATED: How I rediscovered the virtue of citizenship on a remote Canadian island

Buddy Mays/Getty Images

Buddy Mays/Getty Images

The cycle of care

Every sensory detail — the cold pipeline, the mudflats, the weight of the rake — anchors memory to place, making past and present inseparable.

Trust and love, learned in my father’s shadow, now guide me as I support him. The cycle of care turns gently but inexorably.

My father’s name is Peter. As his name suggests, he was always my rock — my moral guide — and I followed him with a child’s absolute confidence. Now the roles have quietly reversed. I lead; he leans on my shoulder.

The symbolism of the tippet — its fragility and strength — mirrors this transfer of responsibility. In angling, the tippet is the thinnest section of line, the point most likely to fail. As I watch my father struggle with the nylon — his hands, calloused by 50 years of labor, unable to tie the hook — it becomes clear that we are in the tippet phase of our relationship.

I take over, tying a grinner knot. He has taught me this a thousand times, but today feels different. As I pull the knot tight, I feel the weight of his legacy. He is handing over the keys to his kingdom.

The weight of a soul

At daybreak the following morning, we set off with the same excitement I once felt as a 5-year-old. His unspoken lesson had always been that disappointment should be met with patience. Then there it is: a solitary bass, glistening in the early sun. His hands tremble as he holds it up, smiling. On the walk back to the car, we laugh as seagulls swoop in, trying to steal our catch.

As our roles shifted, so did my understanding. Fishing became a meditation on acceptance, mortality, and shared silence. Fishing with a dying father reminds you that life is finite. It shows that the boundary between this world and the next is as thin as a fishing line — fragile, transparent, yet strong enough to bear the weight of a soul.

Even after loss, the rituals persist. Each return to Stiffkey is both goodbye and renewal. The year after his death, I returned to scatter his ashes. As the wind carried him out to sea, I understood that life’s true tippet strength is not measured by where it breaks but by what it can hold before it does.

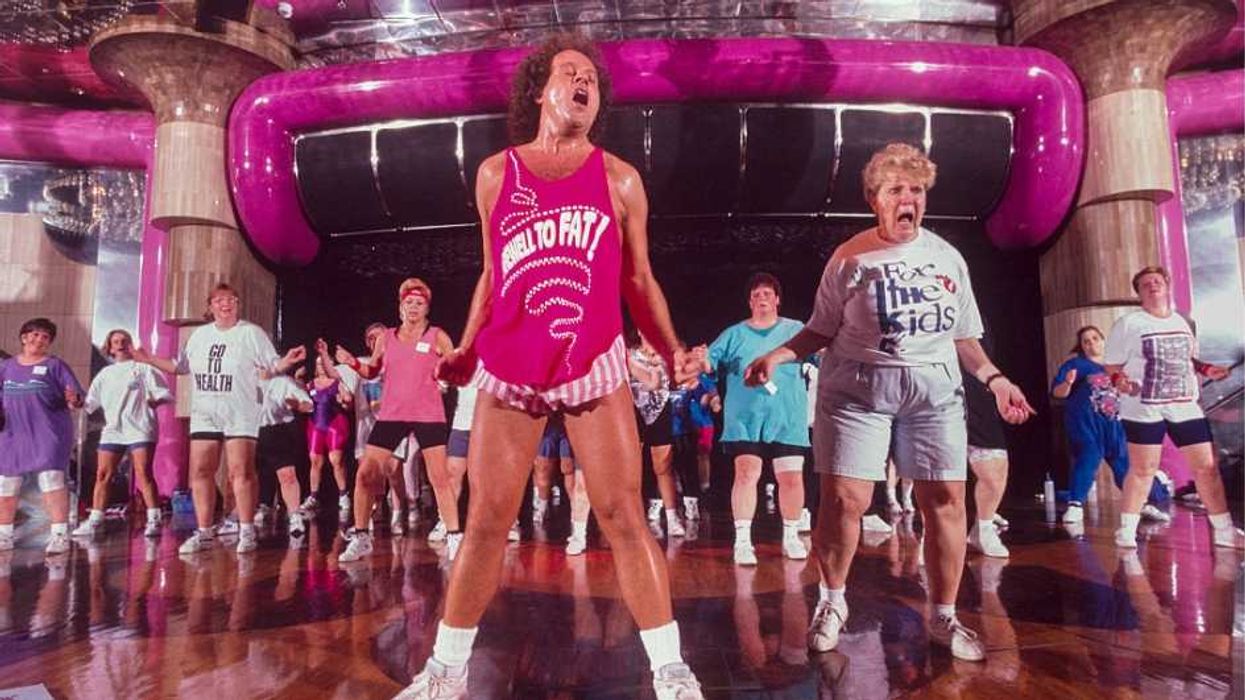

Ozempic no replacement for willpower when it comes to weight loss

A new meta-study — a study of studies — reveals an inconvenient truth about weight loss itself: Willpower still matters. Manufacturers of GLP-1 injectables like Wegovy and Ozempic would prefer we forget that, since forgetting it is profitable.

The counter-claim — that diets and exercise are no match for our genes and environment — is one fat-positivity influencers have pushed for years. Now it has been eagerly adopted by companies like Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly to market their new, lizard-venom-derived blockbuster drugs.

People who stop taking weight-loss drugs regain weight at an average rate of 0.4 kilograms per month — roughly 10 pounds per year.

Business is booming. One in eight American adults have taken a weight-loss drug at one time — and this is only the beginning. Uptake remains far below its theoretical ceiling: More than 70% of U.S. adults are overweight or obese, including roughly 40% who are clinically obese.

Shred-pilled?

What comes next is obvious. Adoption will surge as delivery methods improve, especially pills. People don’t like needles. Pills are much easier to swallow.

Just before Christmas, the Food and Drug Administration approved a pill version of Wegovy, imaginatively branded the Wegovy Pill. Pill versions of competing drugs, including Mounjaro, are expected to follow this year.

Some time ago, I predicted that a weight-loss drugmaker would become the largest company in the world within a decade. I made that prediction when Novo Nordisk — the Danish maker of Wegovy and Ozempic — became Europe’s most valuable company, with a market capitalization of roughly $570 billion, more than $200 billion greater than Denmark’s entire GDP. (It has since fallen a few spots.) I now refine that forecast: The pharmaceutical company that perfects the weight-loss pill — balancing results, side effects, and cost — will be the largest company on Earth.

There are already more than one billion obese people worldwide. There is no obvious reason why every one of them couldn’t be prescribed a daily pill.

RELATED: Fat chance! Obese immigrants make America sicker

Gilles Mingasson/Getty Images

Gilles Mingasson/Getty Images

Chubby checkers

Which brings us back to the meta-study. One of the central unanswered questions surrounding these drugs is what happens when patients stop taking them. Does the weight stay off — or does it return?

In practice, many people don’t stay on them long. Roughly half of users discontinue weight-loss drugs within a year, most often citing cost and side effects, which can include severe gastrointestinal distress, vision problems, and — in rare cases — death.

What happens after discontinuation matters enormously. If the weight returns, many users will be forced to remain on these drugs indefinitely — possibly for decades — to avoid relapse. Pharmaceutical executives have generally been reluctant to acknowledge this implication, though some have done so candidly.

Habit-forming

The researchers behind the new meta-study asked a sharper question still: How does stopping weight-loss drugs compare with stopping traditional interventions like diet and exercise?

The answer is stark. People who stop taking weight-loss drugs regain weight at an average rate of 0.4 kilograms per month — roughly 10 pounds per year. That is four times faster than the weight regain seen in people who stop exercising and restricting calories.

Four times.

The explanation is not mysterious. Pills do not build habits. Diet and exercise do. With drugs, appetite suppression is outsourced to chemistry rather than cultivated through discipline. Remove the compound, and users are left with the same reserves of willpower they had before. Evidence so far suggests that changes to brain chemistry, hormone signaling, and metabolism fade along with the drug itself.

Even when people who diet and exercise relapse, the habits they developed tend to soften the fall. That counts for something.

None of this is to deny that weight-loss drugs can be a valuable tool. For many severely obese people, they may represent the only realistic chance of meaningful weight reduction. If we want to reduce the burden of chronic disease, drugs like Wegovy will have a role to play.

But their rise should not excuse the abandonment of harder truths. Sustainable weight loss still depends on choices, habits, and character — and on reshaping a food environment that makes bad choices effortless and good ones rare. Pharmaceuticals may assist that work. They cannot replace it.

Auto industry • Blaze Media • Hybrids • Jeep • Lifestyle • Stellantis

Jeep just pulled the plug on the hybrids — and no one is saying why

Jeep once bet big on electrification. The pitch was simple: Keep everything that made a Jeep a Jeep — capability, toughness, identity — while adding electric efficiency. For a brief moment, that bet worked.

The Wrangler 4xe didn’t just sell; it dominated. It became the best-selling plug-in hybrid in the U.S., proof that electrification could succeed when it respected consumer priorities instead of lecturing buyers. The Grand Cherokee 4xe followed, extending the same formula into a more refined family SUV without stripping away Jeep’s DNA.

Jeep owners are famously loyal. They tolerate compromises in ride and refinement for capability and character. What they won’t tolerate is silence.

Stellantis had managed what many automakers could not: Electrify without alienating loyal customers.

And then, almost overnight, they vanished.

Without a trace

Without warning or meaningful explanation, the Wrangler 4xe and Grand Cherokee 4xe disappeared from Jeep’s website. They can’t be ordered. EPA ratings for future model years are missing. Dealers are under stop-sale orders. More than 320,000 vehicles are tied up in recalls involving serious safety risks.

This is not how a confident automaker behaves. So what happened?

The 4xe lineup wasn’t a side project. It was central to Stellantis’ North American strategy — key to meeting fuel-economy rules while keeping Jeep profitable. The Wrangler 4xe, in particular, became a regulatory and marketing success story. Until reality caught up.

At the center is a massive recall affecting more than 320,000 Wrangler and Grand Cherokee 4xe models due to a high-voltage battery defect that increases fire risk. That alone is enough to halt sales and shake confidence.

Compounding the problem is a separate recall involving potential engine failure caused by sand contamination. Together, these aren’t isolated issues; they point to deeper quality-control problems in vehicles meant to represent Jeep’s future.

Alarming distinction

Owners have been raising concerns for months — electrical faults, warning lights, charging failures, erratic performance. Consumer Reports recently named the Wrangler 4xe the most unreliable midsize SUV in its annual survey, an alarming distinction for a brand built on durability.

In some cases, fixes amount to a software update. In others, the battery pack fails validation and must be replaced entirely. That difference matters. High-voltage batteries are among the most expensive components in any vehicle, and replacing them at scale creates serious financial strain — even for a global automaker.

For consumers, it raises uncomfortable questions about long-term ownership, resale value, and whether risks were passed on before these vehicles were truly ready.

RELATED: Hemi tough: Stellantis chooses power over tired EV mandate

Global Images Ukraine/J. David Ake/Getty Images

Global Images Ukraine/J. David Ake/Getty Images

Good on paper

Plug-in hybrids were sold as the sensible middle ground — the stable bridge between internal combustion and full electrification. On paper, the Wrangler 4xe looked ideal: 375 horsepower, strong torque, and about 21 miles of electric-only range for daily driving.

What buyers didn’t sign up for was uncertainty.

The implications extend beyond Jeep. Stellantis invested billions in batteries, EV platforms, and software-driven vehicles. The 4xe lineup wasn’t optional; it was essential. When a segment leader quietly pulls its products, it sends a message that the challenges are deeper than advertised.

It also exposes the growing gap between political mandates and engineering reality. Automakers were pushed aggressively toward electrification before infrastructure and consumer demand were ready. Some products were rushed to meet timelines. When expectations collide with reality, trust erodes fast.

With regulatory pressure easing, hybrids are no longer a necessity — and Stellantis’ commitment to plug-ins appears to have cooled.

Loyalty test

Jeep owners are famously loyal. They tolerate compromises in ride and refinement for capability and character. What they won’t tolerate is silence. Removing vehicles without explanation feels less like caution and more like avoidance. Existing owners worry about support and resale value. Future buyers are questioning whether plug-in hybrids are really the smart compromise they were promised.

Stellantis may eventually fix the recalls and relaunch the models. But perception matters, and damage has already been done.

If Jeep wants consumers to believe in its electrified future, it will need more than quiet fixes and lifted stop-sales. It will need transparency, accountability, and proof that innovation doesn’t come at the expense of reliability.

Because hiding information isn’t leadership — and Jeep, of all brands, should know that.

Why speed limits don’t make our highways safer

Speed limits are the most ignored law in America. Everyone knows it, everyone does it, and politicians pretend they don’t.

Yet despite near-universal noncompliance, speed limits keep trending upward. That sounds backward — but there’s a reason. And if we want safer, smarter roads, we need to be honest about how limits are set, why they fail, and what would actually fix them.

Speed limits aren’t broken because speed itself is dangerous. They’re broken because the system is disconnected from reality.

This isn’t about reckless driving. It’s about reality. America’s speed policy is built on outdated assumptions, inconsistent enforcement, and political fights that have little to do with safety. Dig into the data and one thing becomes clear: The current system isn’t working.

And no — an American Autobahn isn’t coming anytime soon.

The risk everyone ignores

Speed limits aren’t chosen on a whim. They’re usually based on the 85th percentile rule: Engineers measure how fast drivers already travel, and the speed that 85% stay under becomes the benchmark.

In theory, this reflects real-world behavior. In practice, when most drivers already exceed posted limits, every traffic study pushes numbers higher. It becomes a feedback loop: People speed, limits rise, people keep speeding. The result isn’t safer roads — it’s inconsistency, which is far more dangerous than speed alone.

Safety debates fixate on top speed, but the real danger is speed variability — the difference between how fast vehicles are moving relative to each other.

A road where some drivers do 55 mph and others do 80 mph is dangerous not because of the fastest car, but because of the difference. High variability leads to congestion, abrupt lane changes, tailgating, and road rage. Uniform speeds are far safer. America fails here because limits don’t match behavior, enforcement is sporadic, and real-world speeds vary wildly.

Unsafe at any speed

Some argue we should simply raise limits to match reality. But the data doesn’t support that.

Outdated limits do breed distrust, but raising limits without fixing enforcement, road design, and driver training only widens speed differences. There’s also a political ceiling: Higher limits face resistance that has little to do with safety.

Insurance companies have long resisted higher limits. Greater speeds can mean more severe crashes, higher payouts, and larger claims — so insurers lobby accordingly.

Then there’s Vision Zero and its “safety over speed” movement, which prioritizes lower limits, stricter enforcement, and speed cameras to reduce fatalities. Critics argue it oversimplifies the problem by blaming speed while ignoring poor infrastructure, distracted driving, and inconsistent enforcement. The result is a political stalemate divorced from what actually works.

Why we can’t drive 55 … or 85

The Autobahn always comes up in these debates, and for good reason. It works because everything aligns.

German driver training is rigorous, emphasizing lane discipline and high-speed control. Left lanes are strictly for passing. Roads are engineered for sustained speed. Enforcement is consistent and focused on the right behaviors — tailgating, lane blocking, and distraction.

You can’t copy just one piece of that system and expect the same result.

The national 55 mph limit of the 1970s was widely ignored and eventually repealed. Safety gains were modest and short-lived, while frustration and economic costs were substantial. Arbitrary limits without public trust don’t last.

RELATED: Mandatory speed limiters for all new cars — will American drivers stand for it?

Vintage Images/Getty Images

Vintage Images/Getty Images

Brake check

Do speed limits actually work?

Yes — but only when they align with road design, real driving behavior, consistent enforcement, competent driver training, and low speed variability. Right now, America misses on nearly all counts.

Speed limits aren’t broken because speed itself is dangerous. They’re broken because the system is disconnected from reality. The solution isn’t simply raising or lowering numbers — it’s aligning engineering, enforcement, training, and expectations.

America’s biggest problem isn’t speed. It’s inconsistency. Until that changes, noncompliance will continue — and so will preventable crashes. Smarter speed policy won’t come from politics. It will come from practical engineering, and that would save more lives than any number posted on a roadside sign.

Blake's progress • Blaze Media • Culture • Lifestyle • Nightlife • Portland

FACTION NEWS: The day the media taught me it’s always wrong to be right

My first experience with an activist journalist came in 2019. I had traveled to Oregon’s state capitol in support of a small group of Republican state legislators. They had refused to appear for a vote, to prevent the Democrats from passing a hotly contested education bill.

This was a strategy the Republicans had used before. Oregon is a solid blue, Democrat-run state. Often, the only tool the Republicans had to stop a bad bill was to leave town and thus deny the legislature their quorum (the necessary number of legislators needed to vote).

Did she really hate Republicans so much, she couldn’t contain her rage for the 10 seconds she was required to listen to my answer? She was a professional news reporter.

So that’s what they did. The Democrats were up to their usual money-wasting, ideology-pushing ways. So the Republicans went AWOL.

Breaking the ice

Our busload of Republican volunteers — about 20 of us — unloaded at the state capitol.

There was media everywhere. The day before, the Democrats had threatened to send the state police after the rogue legislators and drag them back to the capitol building.

To this, one of our more salty, cowboy hat-wearing legislators responded: “Send bachelors and come heavily armed.”

This was about as colorful as politics got here in Oregon.

So that’s why we were there. To show the public that those renegade Republicans had the support of their constituents.

We’d been told to look presentable and interact with the media if possible. I was wearing glasses, a sweater, and a button-down shirt. I looked like a school teacher or maybe a writer (which I am) or one of those retirees who volunteers for things (which I also am).

We gathered in the crowded capitol building. There were reporters and camera crews scattered throughout. I felt like I should break the ice and go talk to one.

I spotted a TV crew from the Portland Fox affiliate. The reporter was dressed up, hair and makeup camera-ready. She was probably 45 years old. She appeared to be a seasoned, professional reporter.

So I walked over to her and said: “Do you guys need to interview a Republican? Do you want a quote?”

“Yeah, sure,” she answered.

Spirited debate

At this point, I was still very new to politics. To me, it still seemed like a game. Like a friendly competition. But that’s what I liked about it. I enjoyed being part of a team and engaging in spirited debate with the other team.

But I also believed in fair play and maintaining a sense of humor. That was my take on the present situation. It was funny. The outlaw Republican cowboys versus the non-binary, they/them Democratic elites? This was a great story!

Which was why it was getting so much attention. And why the capitol was packed with people. Even the national news was covering it.

Seethe the day

The cameraman lifted his camera onto his shoulder. I straightened my sweater and brushed my hair back with my hand.

The reporter asked if I was ready, and I nodded. They turned on the camera.

In her professional voice, the reporter asked me if the Republicans’ leaving town was the proper way to debate an education bill.

She pointed the microphone at me, and I answered, “They’re totally outnumbered. But most people agree with them. So I do think it’s an appropriate strategy.” Or something like that.

That was it. A couple sentences. Clean and simple. She was going to need a quote from someone on the Republican side, so I gave her one.

Not only that, I knew to look at her and not the camera as I spoke. To actually listen to her question before I answered. So it would look good on TV.

But that was the problem. When I looked into her face, she was glaring at me. She had this look in her eyes. It was a look I was not prepared for. I’m not sure I’ve ever actually seen someone look at me like that.

It was a look of total hatred. Like burning, seething hatred. And it was leveled at me! And I was being cheerful and nice. I was helping her out!

Hate on the hour

That look on her face was disturbing. Once they turned the camera off, I just walked away.

What was this woman’s problem? Did she really hate Republicans so much, she couldn’t contain her rage for the 10 seconds she was required to listen to my answer? She was a professional news reporter. She was 45 years old!

If it were some 22-year-old who just graduated from “activist” journalism school, I could understand. But this was a grown woman. Had she never done this before?

Hey, lady: You’re not supposed to HATE people for having an opposing opinion. I DID YOU A FAVOR!

RELATED: ‘Subhuman ghouls’: People, WaPo trash Scott Adams hours after his death

Photo by Bob Riha Jr./Getty Images

Photo by Bob Riha Jr./Getty Images

‘Love’ wins

So now, several years have passed, and I see this same phenomenon almost every night on my local news. Not necessarily seething hatred. But something similar. Specifically: the constant messaging that any conservative position, on any issue, is — of course — totally evil. And that the left is always morally correct.

That’s what I saw in the eyes of that local Fox reporter. A total lack of perspective. A soulless fanaticism. She was like a “hate robot” with one mission: the annihilation of people like me!

Unfortunately, this behavior is commonplace now. The division continues to get worse. I don’t know what the solution is, except to point out that hating people, at this intensity level, can’t be good for your health. If you’re hating and seething, you’re probably hurting yourself more than anyone else.

Blaze Media • Donald Trump • Lifestyle • Mark carney • Nicolas Maduro • Oil

CRUDE AWAKENING: Canada’s pipeline paralysis fumbles American oil market

Canada has exactly the kind of oil the United States needs. But when it comes to investing in the infrastructure to move it, America’s ally to the north is beginning to look as risky — and as politically hostile — as Venezuela.

That, Dan McTeague of Canadians for Affordable Energy tells Align, reflects a perverse governing philosophy towards the country’s energy abundance: “keep it in the ground.”

Carney can talk about buying China’s ‘windmills and solar panels,’ or he can ask whether China wants to buy oil — ‘because we got a pipeline.’

Canada’s self-inflicted pipeline paralysis is eroding its position in the U.S. market just as alternatives like Venezuelan oil come back online.

Oil, oil everywhere

Nowhere is that risk clearer than in Alberta, home to the vast majority of Canada’s oil production, where years of stalled pipeline projects have left the country’s most valuable energy asset effectively landlocked.

Canadian oil is the same kind Venezuela produces: heavy crude, high in sulfur, and ideal for making diesel fuel. Most U.S. refineries are designed specifically to process this type of petroleum, which is essential not just for transportation, but for agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and national defense.

Alberta has long sought to build a pipeline to the West Coast, primarily to secure reliable, long-term access to the U.S. market — while also giving Canada leverage to reach other buyers if American demand weakens or politics intervenes.

That project remains stalled, despite Liberal Prime Minister Mark Carney — who has spent much of his career championing green energy and opposing pipelines — recently signing a memorandum of understanding with Alberta that is supposed to clear the way for construction. Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is now demanding that pipeline construction begin by fall 2026.

Carbon crunch

In practice, the MOU changes little. It grants no approvals, streamlines no federal reviews, resolves no indigenous or legal challenges, and commits no public capital. By tying any future pipeline to rising carbon tax and decarbonization requirements, it arguably worsens the investment case — leaving no private sponsor willing to move first.

While the United States remains Canada’s natural customer, a West Coast outlet still matters. It gives producers pricing power, optionality, and insurance against sudden policy shifts in Washington — precisely the kind now emerging as Venezuela re-enters the picture.

The question is who would build such a pipeline — and whether it could be completed before the United States turns to cheaper Venezuelan oil to fill the gap.

Venezuela of the north?

President Donald Trump has floated asking oil companies for $100 billion to build infrastructure in Venezuela capable of moving oil north. Exxon’s CEO rejected the idea, calling Venezuela “uninvestable” because of its history of asset seizures and nationalization. Trump, however, could choose to push the project forward with public funds.

McTeague — himself a former Liberal member of Parliament — says Canada has made itself similarly unattractive to investors. He argues that policy choices — not geology — are the problem.

Canada, he says, is “blessed with abundance of resources,” but has embraced a governing narrative that tells producers to “keep it in the ground.” He adds that few countries would treat their most important economic output that way.

That mindset, McTeague argues, has frightened off private capital and left Ottawa with little choice but to build a pipeline itself. It also raises the stakes of Carney’s upcoming trip to China — not as a pivot away from the U.S., but as leverage.

Tilting at windmills

When Carney arrives in Beijing, McTeague says, he faces a choice. He can talk about decarbonization and buying China’s “windmills and solar panels,” or he can ask whether China wants to buy oil — “because we got a pipeline.”

The point, McTeague stresses, is not that China should replace the United States as Canada’s primary customer, but that Canada needs credible alternatives if it wants to be taken seriously by either.

McTeague also criticizes the MOU’s requirement that the industrial carbon tax rise sharply in coming years, arguing that it “defies economics and the realities of the marketplace.” In his view, decarbonization mandates are irrelevant to investors deciding whether a pipeline is worth building.

Time, he warns, is running out. Federal debt continues to grow, and Canada’s fiscal credibility is beginning to erode. Without pipelines, he says, the country risks running out of economic runway.

RELATED: The truth behind Trump’s Venezuela plan: It’s not about Maduro at all

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Over a barrel

McTeague also disputes the claim that the United States is energy-independent. While America produces roughly 12 to 13 million barrels of oil per day, it consumes about 21 million — leaving it dependent on imports.

Canada’s value, he argues, lies not just in volume, but in the type of oil it produces. U.S. shale oil is well suited for gasoline, but not for diesel, which he calls the global workhorse of modern economies — critical to transportation, agriculture, industry, and defense.

That is precisely the fuel Venezuela is now offering, potentially at a lower cost than Canadian oil burdened by carbon taxes and regulatory constraints.

Canada now finds itself between a rock and a hard place: Venezuelan oil threatening to undercut U.S. demand for Alberta crude, plus the political and logistical reality of building a major pipeline through British Columbia — on a timetable that is rapidly running out.

In energy terms, Canada is doing the unthinkable: choosing to be bypassed.

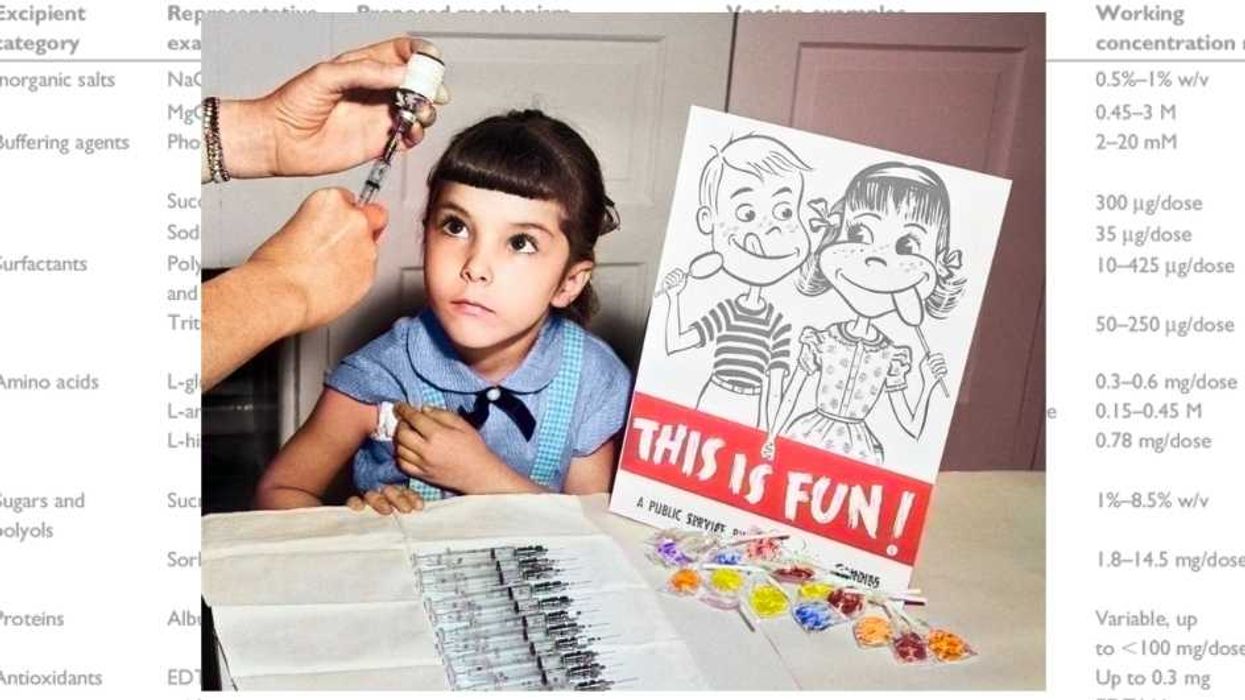

Finally: Vaccine guidelines that make sense for parents

Filmmaker and mother Jessica Solce was frustrated by the difficulty of finding healthy, all-natural products for herself and her family. To make it easier, she created the Solarium, which curates trusted, third-party-tested foods, clothing, beauty products, and more — all free of seed oils, endocrine disruptors, carcinogens, and other harmful additives.

In this occasional column, she shares recommendations and research she has picked up during her ongoing education in health and wellness.

On Wednesday, the CDC moved six childhood vaccines out of the “recommended for all” schedule.

For those of us advocating for the right to oversee our own children’s health, it was a day we thought would never come. It is a moment of triumph, but also a reminder of the fear and pressure we have had to overcome.

When my child was just three days old, I was yelled at and expelled from a pediatrician’s office for simply asking about delayed vaccination.

I joined the fight in 2009, not long after becoming pregnant with my first child. My parents brought me up to question and test everything; as I prepared to become a parent myself, this tendency quickly found a new target: childhood vaccinations.

While many mothers-to-be were already signing their future babies up for preschools, summer camps, and Mandarin lessons, I was staying up at night immersed in research that challenged conventional wisdom about children’s health. In 2009, that kind of information was far harder to track down than it is today.

Mother lode

But track it down I did. That’s how I found the work of the Weston A. Price Foundation, as well as the writings of Dr. Lawrence Palevsky. I began reading with the intention of writing a kind of thesis paper — something rigorous enough to convince myself and honest enough to defend to my family.

At the time I encountered his work, Dr. Palevsky was not what most people would call “anti-vaccine.” He recommended delaying vaccination until age two, avoiding live-virus vaccines except for smallpox, spacing doses by six months, and administering only one vaccine at a time.

This seemed reasonable to me.

Brain drain

Why? [Checks 2009 notes.] Based on Dr. Palevsky’s work, I believed that vaccines could activate microglia — the brain’s specialized immune cells — and that closely spaced vaccinations might overstimulate this system during early brain development.

The most rapid period of brain development begins in the third trimester and continues through the first two years of life. Vaccinating children under two, according to this line of thinking, could increase the risk of neurological issues, asthma, allergies, autoimmune conditions, and chronic inflammation. By age two, the brain is roughly 80% developed, and the view then was that certain vaccines could be introduced very slowly after that point.

So I weighed risk and reward. With a healthy baby in my care, why would I take what I believed to be a neurological risk?

That was enough to harden my resolve. I armed myself for what became a 10-year battle in New York City.

Dr. Doomer

When my child was just three days old, I was yelled at and expelled from a pediatrician’s office for simply asking about delayed vaccination. I had printed multiple copies of my small “thesis paper,” like a diligent student, and in a moment of panic and adrenaline shoved them into office drawers as I held my newborn and was escorted out.

But the doctor’s tirade — invoking her intelligence, her own vaccinated children, and her authority as a physician, all while calling me an idiot — only strengthened my resolve. To me, it suggested someone constrained by her own choices, guilt, and lack of curiosity.

Even my father, a physician himself, was initially stunned when I began laying out my reasoning. But through heated debate, shared papers, and real discussion — the healthy kind — he eventually reflected on his own training and acknowledged that he had been taught to comply, not to question.

RELATED: Trump administration overhauls childhood vax schedule. Here’s the downsized version.

Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Hold the formaldehyde

For anyone ready to do some research of their own, I recommend starting with the CDC’s Vaccine Excipient Summary, which lists the inactive ingredients contained in licensed vaccines. Perhaps you’ll ask yourself, as I did, whether you want substances like formaldehyde, aluminum phosphate, polysorbate 80, β-propiolactone, neomycin, and polymyxin B injected into your child’s developing body.

Once I began asking that question, it was impossible not to look at how vaccine policy had evolved. A major inflection point, in my view, came in 1986 with the passage of the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, which shielded vaccine manufacturers from direct liability and moved injury claims into a federal compensation system. After that, vaccine development accelerated.

Today I’m in a celebratory mood, despite how long it has taken to get here. I don’t regret the fight for a second; I only wish I had had more courage and stamina at times. Still, I rejoice in every freedom of choice returned to parents in the United States.

Let’s go, MAHA. Now do the EPA.

search

calander

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

categories

Archives

navigation

Recent posts

- Gavin Newsom Laughs Off Potential Face-Off With Kamala In 2028: ‘That’s Fate’ If It Happens February 23, 2026

- Trump Says Netflix Should Fire ‘Racist, Trump Deranged’ Susan Rice February 23, 2026

- Americans Asked To ‘Shelter In Place’ As Cartel-Related Violence Spills Into Mexican Tourist Hubs February 23, 2026

- Chaos Erupts In Mexico After Cartel Boss ‘El Mencho’ Killed By Special Forces February 23, 2026

- First Snow Arrives With Blizzard Set To Drop Feet Of Snow On Northeast February 23, 2026

- Chronological Snobs and the Founding Fathers February 23, 2026

- Remembering Bill Mazeroski and Baseball’s Biggest Home Run February 23, 2026